Fig. 27.1

a Distance to popliteal artery in extension. b Increased distance to popliteal artery in knee flexion. (From Ref. [22]. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier Limited)

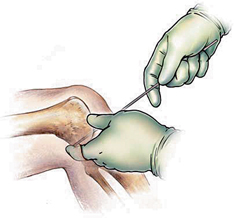

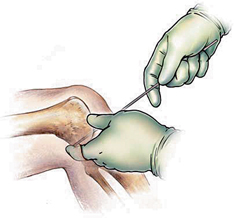

Fig. 27.2

Popliteal artery injury during posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. (From Ref. [1]. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier Limited)

Several techniques have been developed to decrease the risk of this feared complication. Knee flexion to 100° increases the distance between the posterior tibia and popliteal neurovascular bundle [22]. Posterior capsular release off of the proximal posterior tibia can also increase the distance to the neurovascular structures [25] (Fig. 27.3). Fluoroscopy can be used to monitor the position of the guidewire and reamer [11]. Guide pins can be inadvertently advanced while reaming occurs, so great care should be used to either arthroscopically or radiographically visualize or palpate the guide pin and reamer. The guide pin or reamer can be advanced by hand through the posterior cortex to enter the fossa in a controlled fashion. Specialized guides that have a large backstop to prevent the excessive advancement of the guide pin or reamer can be used to decrease the risk of penetration. Retrograde cutting techniques also decrease the risk of injuring posterior structures, although anterograde drilling remains a part of these procedures. A PM safety incision as described by Fanelli [26] (Fig. 27.4) allows the surgeon to place their fingers extracapsular to protect the neurovascular bundle [11]. Similarly, the open tibial inlay procedure uses a similar interval and retractors to protect the popliteal artery and nerve.

Fig. 27.3

Increased distance after a tibial-side posterior capsule release. (From Ref. [25]. Reprinted with permission from SAGE Publications)

Fig. 27.4

Posteromedial safety incision. (From Ref. [40]. Reprinted with permission from WB/Saunders Co)

Osteonecrosis of the medial femoral condyle has been reported from PCL reconstruction [27]. The extraosseous and intraosseous blood supply to the medial femoral condyle is more tenuous than the lateral femoral condyle [28]. Drilling the femoral tunnel for PCL reconstruction, may cause injury to the single nutrient vessel found in the medial femoral condyle. Osteonecrosis of the medial femoral condyle can lead to continued medial-sided knee pain [11, 27, 28]. Prevention of this complication can be accomplished by leaving a sufficient bone bridge of 8–10 mm between the femoral tunnel and the articular surface of the medial femoral condyle [11].

Tibial fractures are a rare complication of PCL reconstruction . This can occur if the tunnel is too large. It is also seen in double-bundle PCL reconstruction or combined ACL/PCL reconstructions if the tunnels converge. Thus, to prevent this complication, one must have divergent tunnels. In addition, tibial fractures have been reported during hammering a staple for fixation [11, 23]. Patellar or tibial fractures can also occur due to bone–patellar tendon–bone (BPTB) harvesting. The reported rate for fracture during BPTB harvesting during ACL surgery ranges from 0.2 to 2.3 % [29–31].

Other complications that can arise intraoperatively are related to the use of a tourniquet and compartment syndrome. Tourniquets can help provide a bloodless field for operating, but this does not come without potential complications. Muscle injury, nerve injury, metabolic dysfunction, coagulopathy, and deep vein thrombosus have all been reported [32]. Compartment syndrome after knee arthroscopy has been reported and is a rare complication. This can occur by a rent in the capsule, which leads to fluid extravasation in the operative leg [23, 33]. In addition, positioning can result in compartment syndrome of the contralateral extremity, including a case report of gluteal compartment syndrome after PCL reconstruction [23].

Postoperative Complications

There are several complications that can arise is the postoperative period after PCL reconstruction . These include continued laxity, stiffness, anterior knee pain, painful hardware, heterotopic ossification (HO), and infection. A continued laxity after surgical reconstruction of the PCL can be due to both bony and soft tissue problems. A malalignment of the lower extremity with a varus deformity at the knee leads to a lateral thrusting gate. This can have a deleterious effect on a PCL reconstruction if not corrected prior to PCL reconstruction with a high tibial osteotomy [11, 34].

When the limb alignment is normal and there is persistent laxity, soft tissue problems are most likely the culprit. Inaccurate diagnosis of associated ligament injuries can lead to increased instability. This is particularly true with an unrecognized posterolateral corner injury (PLC). When there is a PLC injury and it is not reconstructed with a concomitant PCL injury , the posterior tibial insertion of the PCL rotates medially and anteriorly. This leads to a relative shortening of the distance from the medial femoral condyle to its tibial insertion, resulting is a functionally lax PCL [11]. A missed diagnosis can be avoided by a diligent physical exam and careful review of MRI . Technical errors in the PCL reconstruction is another soft tissue reason for the continued laxity. Early graft loading during rehabilitation can lead to laxity and clinical instability [23]. Femoral tunnels placed too posterior and/or proximal to the femoral isometric point, lead to decreased graft tension in flexion, and thus the knee feels lax [23, 35]. In addition, insufficient graft size and strength and improper graft tensioning can lead to knee laxity [11, 35, 36]. The use of a tensioning boot may avoid excess laxity. Meticulous surgical technique and rehabilitation are key to help avoid these problems.

Loss of flexion after PCL reconstruction is more common than the loss of extension [37]. The loss of flexion becomes functionally limiting when the patient is limited to 110° or less. This can be due suprapatellar adhesions, arthrofibrosis, improper tunnel placement, improper graft tensioning, nonisometric nature of the PCL, multiligamentous procedures, and poor compliance with physical therapy [11, 23]. Suprapatellar adhesion can occur after an arthrotomy or bone-quadriceps tendon autograft harvesting. These adhesions lead to loss of flexion. These patients can be treated with manipulation under anesthesia and arthroscopic lysis of adhesions [11, 23]. Femoral tunnel placement leads to loss of flexion when they are located too anterior and/or distal to the femoral isometric point [23, 35]. Fanelli and Monahan reported on 120 PCL injuries, most of them combined ligament injuries. They found an average of 10° loss of flexion and 5.4 % required lysis of adhesions and manipulation [11]. In addition, the inherent nonisometric nature of PCL reconstructions to reproduce the complex arrangement of the PCL fibers leads to the loss of flexion [11, 23].

Anterior knee pain after PCL reconstruction is the result of continued laxity, prominent hardware, or donor-site morbidity. When the reconstructed PCL is lax, there is a continued posterior sag of the knee with patella baja. This will lead to an increase in contact pressure in the patellofemoral joint, causing anterior knee pain [11, 17, 18]. Prominent hardware can cause anterior knee pain. This can be treated by removing the fixation device [11]. If autologous BPTB is harvested for PCL reconstruction, there can be donor-site morbidity presenting as anterior knee pain. This can be prevented by taking a graft no larger than the central third of the patellar tendon, taking bone plugs with oscillating saw instead of osteotomes to minimize chondral injuries, and taking patellar plug not be more than inferior two thirds of patella and not more than one third the thickness of the median ridge [11, 23].

HO has been reported in the literature as a complication following PCL reconstruction . There are rare case reports describing posterolateral capsular HO believed to be the result of femoral tunnel reaming. If the HO is prominent, it can affect a patient’s range of motion. In these cases, removing to HO should improve a patient’s range of motion [23].

Wound infections and septic arthritis are complications of all operative procedures. In ACL reconstruction, meniscal repair and prior knee surgery were found to increase the risk of infection [38, 39]. Wound dehiscence can occur when large flaps are not raised, specifically during the tibial inlay technique for PCL reconstruction . Prophylactic antibiotics prior to the start of the case, careful soft tissue handling, adequate skin bridges, and thick subfascial flaps can decrease these complications [11].

Conclusion

Overall, our knowledge of PCL reconstruction technique is lacking when compared to ACL reconstruction. Because of this, our complication rate is significantly higher. This chapter was meant to review potential complications we face when treating PCL injuries, both nonoperatively and operatively. As our understanding of the PCL increases in the future, our complication rate will subsequently decrease, evidenced by our improvement in ACL reconstruction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree