Chapter 11 Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Integration into Primary Care

Complementary and alternative medicine is based on multiple healing traditions practiced long before conventional Western medicine. Emerging from diverse cultural traditions worldwide, these approaches to health and healing offer the wisdom of their unique perspective on the human condition. Many traditional practices, including those of conventional medicine, share common roots and philosophies and uphold the sacred call to relieve the suffering of others. Family physicians should keep an open mind as they explore these dimensions of CAM.

What Is Complementary and Alternative Medicine?

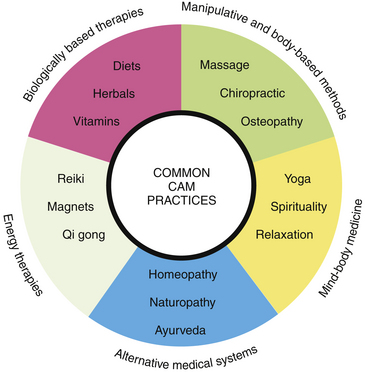

The NCCAM further classifies CAM into five categories, or domains (Figure 11-1). Examples of alternative or whole medical systems include homeopathy, naturopathy, and Ayurveda (eAppendix 11-1 provides a glossary of CAM terms online at www.expertconsult.com). Although there are a variety of approaches to the complex taxonomy of CAM (Kaptchuk and Eisenberg, 2001b), the NIH system is most often used.

Another term, holistic medicine, also describes these practices and philosophy. The American Holistic Medical Association (AHMA), founded in 1978, is a membership organization for physicians and other health professionals seeking to practice a broader form of medicine than that currently taught in allopathic medical schools (Table 11-1). “Holistic medicine is the art and science of healing that addresses care of the whole person—body, mind, and spirit. The practice of holistic medicine integrates conventional and complementary therapies to promote optimal health and to prevent and treat disease by addressing contributing factors” (AHMA, 2005).

Table 11-1 Important Events in Complementary and Integrative Medicine

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1978 | American Holistic Medical Association is founded. |

| 1981 | American Holistic Nurses Association is founded. |

| 1992 | U.S. Office of Alternative Medicine (OAM) is established. |

| 1996 | U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approves acupuncture needles for use by licensed practitioners. |

| 1998 | National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) is established, replacing OAM. |

| 1999 | Consortium of Academic Health Centers for Integrative Medicine (CAHCIM) is formed in response to increasing public interest in complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and grows to 46 members by 2010. |

| 2000 | American Board of Medical Acupuncture is established, with a certifying examination for physicians to demonstrate proficiency in the specialty of medical acupuncture. |

| 2000 | President Clinton appoints James S. Gordon, MD, to chair the first White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine Policy (WHCCAMP). |

| 2002 | WHCCAMP submits final report with administrative and legislative recommendations for maximizing the benefits of CAM for all Americans. |

| 2005 | |

| 2006 | CAHCIM sponsors the first North American Research Conference on Complementary and Integrative Medicine. |

| 2009 |

Integrative medicine is healing oriented and emphasizes the centrality of the doctor-patient relationship. It focuses on the least invasive, least toxic, and least costly methods to help facilitate health by integrating allopathic and complementary therapies. These are based on an understanding of the physical, emotional, psychologic, and spiritual aspects of the individual.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use in the 1990s

The first major study of CAM use in the United States was conducted in 1990 by David Eisenberg and colleagues (1993), who published a landmark paper in the New England Journal of Medicine. Serving as a wake-up call to conventional medicine, the data from this national telephone survey of 1539 English-speaking adults estimated that one of three Americans (34%) had used a CAM therapy in the prior year. The study estimated that those using CAM had made 425 million visits to complementary medicine practitioners—more than all office visits to primary care physicians in that same time frame! The out-of-pocket costs for these CAM services were approximately $14 billion a year. The striking statistics alerted mainstream medicine and prompted further inquiry into the growing phenomenon of the public’s use of CAM.

Most concerning was the finding that although CAM use had increased over the 7-year period, the number of patients informing their doctors of such use had not changed—approximately 60% to 70% of CAM users in 1990 and 1997 did not discuss their use of CAM with their physicians. Lack of communication was noted again in a 2006 NCCAM/American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) survey of adults 50 or older revealing only one-third of CAM users had talked to their physicians about their CAM use (AARP, 2007). Given this fact and the potential for untoward side effects, it is essential that physicians and all other health professionals ask patients about their use of CAM. In addition to NCCAM’s “Time to Talk” campaign, several approaches have been suggested (Eisenberg, 1997); Table 11-2 lists an ABC format especially useful for the busy clinician (Sierpina, 2001).

Table 11-2 Guidelines for Advising Patients Who Seek Alternative Therapies

| Ask; don’t tell. |

| Be willing to listen and learn. |

| Communicate and collaborate. |

| Diagnose. |

| Explain and explore options and preferences. |

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use in the 21st Century

Data on the U.S. population’s use of CAM was collected in 2002 and 2007. Considered the most comprehensive and reliable findings on American’s use of CAM, these studies were conducted by the NCCAM and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). For the first time, detailed questions regarding CAM were added into the 2002 edition of the NCHS National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), an annual study interviewing tens of thousands of Americans about their health- and illness-related experiences. The 2002 and 2007 studies were completed by ~30,000 families through adults 18 years or older who spoke English or Spanish. The study reflected CAM use during the 12 months before the survey. The 2007 survey included expanded questions on 36 types of CAM therapies commonly used in the United States—10 practitioner-based therapies, such as acupuncture, and 26 other, self-care therapies not requiring a practitioner. CAM therapies included in the surveys are listed in Table 11-3, and the terms are defined in eAppendix 11-1.

Table 11-3 Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) Therapies Included in 2002 and 2007 National Health Interview Surveys

Definitions of these therapies are provided in the glossary of eAppendix 11-1.

∗ Indicates a practitioner-based therapy.

† Indicates addition to 2007 survey.

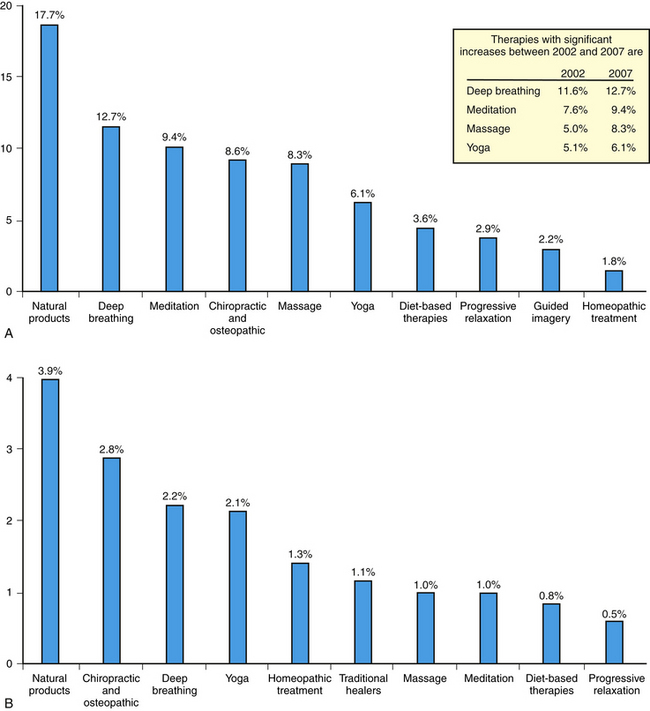

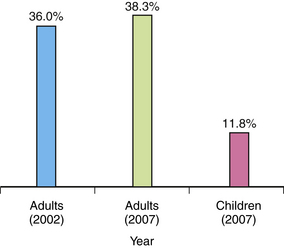

As shown in Figure 11-2, CAM use increased from 36% of U.S. adults in 2002 to 38% in 2007, or almost 4 of 10 adults (Barnes et al., 2004, 2008). For the first time, the 2007 survey collected data on CAM use in children (<18 years), showing 12% use, or 1 in 9 children. The top 10 CAM therapies for both adults and children are shown in Figure 11-3. Significant increases in adults’ use of deep breathing, meditation, massage, and yoga occurred over the 5 years of the study. Another notable NCCAM/AARP study focused on CAM use in adults older than 50 years. Approximately two-thirds (63%) had used one or more CAM therapies (AARP, 2007). The most common reasons cited for not discussing CAM included: the physician never asked (42%), the patient did not know they should ask (30%), and there was not enough time during the office visit (19%). Of those using CAM, 66% did so to treat a specific condition and 65% for overall wellness. For details on CAM costs in the U.S., see eFigures 11-1 to 11-3 online at www.expertconsult.com.

Figure 11-2 Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use by U.S. adults (2002, 2007) and Children (2007).

(From Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin R. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. CDC National Health Statistics Report No 12. December 2008.)

Who Is More Likely to Use CAM, and Why?

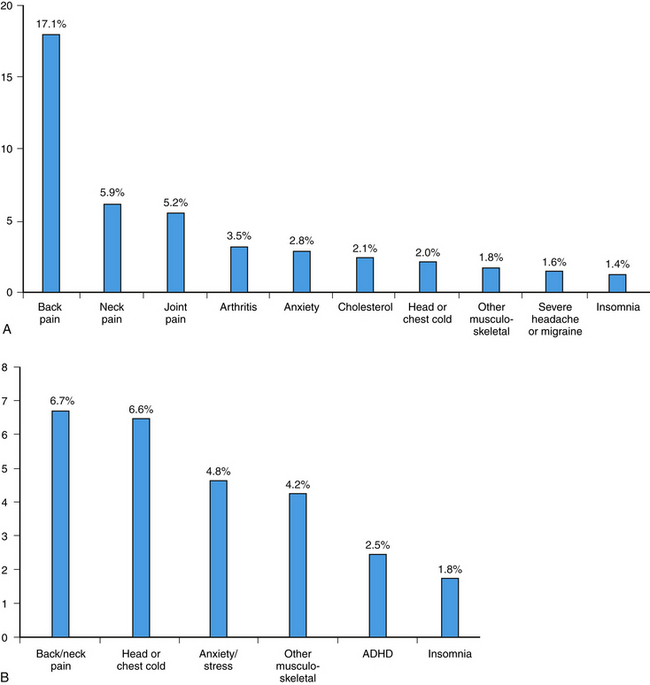

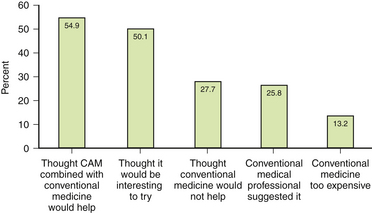

Figure 11-4 shows the disease or condition for which adults and children are most likely to seek CAM. The 2002 survey also addressed the important question: Why do people use CAM? Previous studies revealed general issues of the overuse of technology and a reductionist approach to care, managed-care time constraints limiting visits and eroding the physician-patient relationship, and the explosion of Internet-based information on CAM. Astin (1998) found that along with being more educated and reporting poor health status, most alternative medicine users were not dissatisfied with conventional medicine, but rather found these health care alternatives to be more congruent with their own values, beliefs, and philosophic orientations toward health and life. Only 4.4% reported relying primarily on CAM therapies for their health care. A subsequent study of patients using both CAM and conventional care also found that use of CAM did not primarily reflect dissatisfaction with conventional care (Eisenberg et al., 2001).

Reasons for CAM use reported in the 2002 NHIS study are shown in Figure 11-5, with slightly more than one half of all respondents believing CAM combined with conventional medicine would be helpful.

Trends in CAM Use

The 2002 and 2007 NHIS data show that although the overall prevalence of CAM use by adults had remained relatively stable (36% and 38%, respectively), there have been significant increases in some therapies, including acupuncture, deep-breathing exercises, massage therapy, meditation, naturopathy, and yoga (see Figure 11-3). Several factors may account for this growth, including increasing state licensure of some of the practices and greater public awareness of their use through the press and Internet resources. Characteristics of adult and pediatric CAM users are similar in that education, poverty status, geographic region, number of health conditions, physician visits in the prior year, and delaying or not receiving conventional care because of cost are all associated with CAM use. Overall reasons for CAM use fall into two equal categories: (1) treating a variety of health problems, especially pain, and (2) promoting general health and wellness. Much of CAM use is “self-care” and is mostly used with conventional care.

Important U.S. Reports

White House Commission 2002 Report

The White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine Policy (WHCCAMP) 2002 report was the culmination of 18 months of in-depth work of a committee of 20 appointed commissioners. Their task was to provide the president, through the secretary of Health and Human Services, with a report containing legislative and administrative recommendations that would ensure a public policy that maximized the potential benefits of CAM to all. Specifically, the commission addressed the coordination of research to increase knowledge about CAM products; the education and training of health care practitioners in CAM; the provision of reliable and useful information about CAM practices and products to health care professionals; and guidance regarding appropriate access to and delivery of CAM. Table 11-4 lists the 10 guiding principles the commission endorsed for their process of making recommendations. The final report lists 29 recommendations and more than 100 action steps as a blueprint for shaping future CAM policy.

Table 11-4 Guiding Principles: 2002 White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine Policy

| 1. A wholeness orientation in health care delivery |

| 2. Evidence of safety and efficacy |

| 3. The healing capacity of the person |

| 4. Respect for individuality |

| 5. The right to choose treatment |

| 6. An emphasis on health promotion and self-care |

| 7. Partnerships are essential for integrated health care |

| 8. Education as a fundamental health care service |

| 9. Dissemination of comprehensive and timely information |

| 10. Integral public involvement |

Institute of Medicine 2005 Report and 2009 Summit

Ignoring CAM is not an option. The widespread use of CAM by patients is a mandate to the scientific community to improve our relatively weak scientific understanding of CAM practices. Moreover, health professionals have a duty to their patients to bring these 2 worlds of contemporary medical practice together. The path to this outcome begins with adopting the same standards of evidence.

In 2009, IOM and the Bravewell Collaborative convened a 3-day summit, Integrative Medicine and the Health of the Public. More than 600 scientists, academic leaders, policy experts, health practitioners, advocates, and other participants from various disciplines examined the practice of integrative medicine, its scientific basis, and its potential for improving health. Note how the recurring themes and shared values listed in Table 11-5 resonate with the principles of family medicine and the foundations of the patient-centered medical home (PCMH). Family physician Victor Sierpina shared a vision for integrative medicine and the physician of the future (Table 11-6).

Table 11-5 Recurring Perspectives from IOM Summit on Integrative Medicine and the Health of the Public

| Vision of optimal health: Alignment of individuals and their health care for optimal health and healing across a full life span. |

| Conceptually inclusive: Seamless engagement of the full range of established health factors—physical, psychological, social, preventive, and therapeutic. |

| Lifespan horizon: Integration across the life span to include personal, predictive, preventive, and participatory care. |

| Person-centered: Integration around, and within, each person. |

| Prevention-oriented: Prevention and disease minimization as the foundation of integrative health care. |

| Team-based: Care as a team activity, with the patient as a central team member. |

| Care integration: Seamless integration of the care processes, across caregivers and institutions. |

| Caring integration: Person- and relationship-centered care. |

| Science integration: Integration across approaches to care (e.g., conventional, traditional, alternative, complementary), as the evidence supports. |

| Policy opportunities: Emphasis on outcomes, elevation of patient insights, consideration of family and social factors, inclusion of team care and supportive follow-up, and contributions to the learning process. |

From Institute of Medicine (IOM). Integrative Medicine and the Health of the Public: a summary of the February 2009 summit. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2009, p 5.

Table 11-6 How the Physician of the Future Will Function

| The care process is… | The doctor’s role will be… |

| Patient centered | A navigator |

| Team based | Part of a multidisciplinary team |

| High-touch, high-tech | Grounded in the community |

| Support of social and environmental policies promoting health | |

| And supports patients through… | And will follow… |

| Complementary and alternative practices | Evidence-based, outcome-focused practices |

| Belief that the body helps heal itself | Principles for creations of healing environments |

| The lead of empowered patients |

From Institute of Medicine (IOM). Integrative medicine and the health of the public: summary of the February 2009 summit. Washington, DC, The National Academics Press, 2009, p. 43.

NCCAM Strategic Plan 2010

Now in its third cycle of 5-year strategic planning, NCCAM continues to explore CAM healing practices in the context of science, train CAM researchers, and disseminate authoritative information to public and professional communities. NCCAM’s course for 2010–2014 is to create priority areas of CAM research to focus efforts that would best serve public need while meeting fiscal realities, as guided by four factors: (1) scientific promise, (2) extent and nature of practice and use, (3) amenability to rigorous scientific inquiry, and (4) potential to change health practices.

Nahin and Straus (2001) and Ahn and Kaptchuk (2005) discuss the unique challenges that CAM presents to conventional research approaches in evidence-based medicine (see Chapter 8). Many CAM study therapies are complex and heterogeneous compared with the more familiar single-drug trial of biomedicine. As such, innovative research strategies, such as those for sham acupuncture, will need to be continually developed. CAM may help the science of medicine to further evolve, as reflected on by Linde and Jonas (1999):