Chapter 15 Community Health Promotion

Evolving Opportunities for Physical Therapists

The format of the class is 12 weeks with four students per week working with adults with neuromuscular disabilities. The class meets 1.5 hours per week. The neurologic diagnostic groups represented include spinal cord injury (paraplegia and tetraplegia), Guillain-Barré syndrome, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson disease, stroke, and traumatic brain injury. The program consists of 20 to 30 minutes of warm-up, in a circle and to music, in which each student and each participant choose an exercise or activity. In addition, medicine balls, free weights, Thera-Band, and gymnastic balls are used. This is followed by 30 to 45 minutes of individualized exercise programs to meet each person’s needs. The purpose of the exercise portion of the program is to improve balance, coordination, endurance, flexibility, strength, and mobility. The program is advertised on the INSHAPE Indiana website as a success story.1

The experience brings to life aspects related to the International Classification of Function, Disability, and Health (ICF) because it classifies health-related domains and describes body structures, functions, activities and participation, and interaction with environmental and personal factors.2 The experience also helps students understand the importance of the Surgeon General’s Call to Action (SGCA), which was developed in July 2005 to improve the quality of life for individuals with disabilities through acceptance and better health care.3 In addition, the students are exposed to Healthy People 2020,4 a government initiative that targets those with disabilities as a subgroup of the population. The goals of Healthy People 2020 include elimination of health disparities and reduction of the number of barriers to participation. Finally, the students are exposed to the National Center on Physical Activity and Disability (NCPAD), a web-based research and information center devoted to physical activity and disability.5 The NCPAD is a clearinghouse of resources for exercise, recreation, and other forms of physical activity for persons with disabilities. As such, it is an important tool for rehabilitation professionals and the patients and clients they serve.

The Language of Health Promotion

Future Directions of Community Health Education

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to:

1. Discuss the role of community health promotion in meeting contemporary health care needs.

2. Describe and apply the language and focus of community health promotion.

3. Discuss how health care practitioners have integrated community health promotion into their professional duties.

4. Identify the roles of the physical therapist in promoting community health.

5. Discuss opportunities for incorporating community health promotion into one’s professional activities.

6. Identify strategies and skills physical therapists can use to design and implement community health promotion programs for people with and without disabilities.

7. Describe evidence-based examples of community health promotion programs relevant to physical therapy practice.

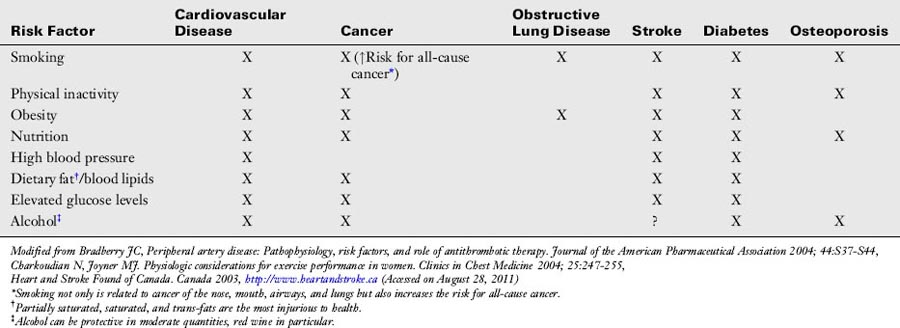

When considering the health issues facing American society, modifiable lifestyle and behavior factors underlie many of the problems challenging our health care system.6 Despite the many efforts to educate U.S. citizens about the importance of healthier lifestyles, the nation’s health still needs significant attention. For example, in 2010 about one third (33.8%) of U.S. adults were obese, and 17% of children between 2 and 9 years of age were obese.7 In any 2-week period of 2005, about 7.3% of Americans reported experiencing clinical depression. Eighty percent of these individuals reported some level of functional impairment, and 27% reported serious difficulties in work and life.8 Only 3 of 10 U.S. adults regularly perform the recommended amount of physical activity, and 37% are not active at all.9 Despite irrefutable evidence of the dangers of cigarettes, almost 18% of adults still smoked in 2009.10 Damaging lifestyle choices are not exclusive to adults. An increasing number of U.S. children have one or more risk factors for one or more unhealthy lifestyle conditions. Some believe that the life expectancy of children in the United States will be less than that of their parents if drastic measures are not taken to change their health choices.11 Table 15-1 summarizes eight modifiable risk factors and their link to some of the leading causes of death and disability.12 The table illustrates how poor lifestyle choices directly and substantially increase the risks for multiple devastating medical conditions. Particularly vulnerable to the negative effects of unhealthy lifestyles are the 40 million Americans currently living with disabilities.13 If one considers those currently living with disabilities, those who will be developing disabilities in the future, and the families of these individuals, a great majority of U.S. citizens will be directly affected by the negative effects of disability if dramatic efforts are not undertaken soon.

In many ways, the U.S. health care system can be described as reactive; most efforts are directed at addressing health problems after they are manifested as illness and disease. Also, health care is traditionally delivered primarily in the clinic or institutional setting on a one-to-one basis between health care practitioner and patient. Further, the primary care physician has been held largely responsible for addressing general health and lifestyle issues with those under their care. Many have come to believe that all members of the health care team should adopt a community-based approach to change unhealthy lifestyle choices (e.g., smoking, obesity, inactivity).14 Also, leaders in many health care professions, including physical therapy, have called on their colleagues to accept responsibility to promote healthier lifestyles among their patients/clients.15,16 This approach to health care, commonly referred to as health promotion, is believed by many to be most likely to significantly improve the health of the U.S. population.

Healthy people initiative

A major driving force behind this different perspective about the nation’s health is the Healthy People initiative—the disease prevention agenda for the United States.4 Healthy People has as its origin the 1979 Surgeon General’s Report, also called Healthy People, which stated that the nation’s health strategy must emphasize the prevention of disease.17 Healthy People 2020 is addressed in detail here because it represents a major touchstone and resource for health care professionals, including physical therapy practitioners, interested in applying their unique professional skills to positively influence the health of U.S. citizens. The Healthy People initiatives provide science-based 10-year national objectives for improving the health of all Americans. The program does this by establishing benchmarks and monitoring progress over time in order to accomplish the following:

• Encourage collaborations across a wide variety of organizations and stakeholders

• Guide individuals toward making informed health decisions

Preceded by Healthy People 2000 and Healthy People 2010, Healthy People 2020 (HP 2020) was launched in December of 2010 and strives to accomplish four overarching goals within the context of the program’s mission (Box 15-1).

Box 15-1 Goals and Mission of the Healthy People 2020 Initiative

Program Goals

1. Attain high-quality, longer lives free of preventable disease, disability, injury, and premature death.

2. Achieve health equity, eliminate disparities, and improve the health of all groups.

3. Create social and physical environments that promote good health for all.

4. Promote quality of life, healthy development, and healthy behaviors across all life stages.

From U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People.gov. Available at healthypeople.gov/2020. Accessed August 28, 2011.

Like the previous healthy people programs, the HP 2020 Framework was developed through an exhaustive collaborative process among the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and federal agencies, public stakeholders, and professional organizations, including the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA).18–20

The National Prevention, Health Promotion, and Public Health Council was established in June 2010 with the intent to move the nation’s focus from sickness and disease to prevention, wellness, and health promotion. The Council uses the following guiding principles19:

• Prioritize prevention and wellness

• Establish a cohesive federal response

• Focus on prevention of the leading causes of death and the factors that underlie them

• Prioritize high-impact intervention

• Promote high-value preventive care practices

• Promote alignment between the public and private sectors

The language of health promotion

To understand how the health of a community can be positively influenced, one must first understand the language of health promotion. The term health promotion is really an umbrella term that encompasses a wide range of concepts. Green and Kreuter21 describe health promotion as any combination of health education and related organizational, economic, and environmental supports for behavior of individuals, groups, or communities conducive to health. Fair describes it as the science and art of helping people change their lifestyle to move toward a state of optimal health.22 As the ultimate goal of health promotion, health is defined by the APTA as not only being free of disease and illness but also including a positive component (wellness) that is associated with quality of life and a positive well-being.23 Fair elaborates on the term wellness, describing it as a lifestyle that promotes physical, mental, and social health in the cognitive, psychomotor, and affective domains, both internally and externally.24 Others include additional aspects of health in their definition of wellness. For example, Hettler describes the dimensions of wellness as including emotional, intellectual, spiritual, occupational, social, physical, environmental, and cultural.25 Jonas added the environment and culture as important dimensions for wellness that should be considered.26 Wellness is not a fixed state of being; instead, it is a dynamic process in which most individuals experience hills and valleys in their state of wellness. Additionally, no dimension of wellness functions in isolation. For example, one’s social wellness likely influences one’s physical wellness. Physical therapists can, and should, address all dimensions of their patients’ wellness. Of these dimensions, physical wellness is most closely related to the physical therapist’s scope of practice. The term fitness is closely related to the dimension of physical wellness. The Guide to Physical Therapist Practice describes fitness as “a dynamic physical state—comprising of cardiovascular/pulmonary endurance, muscle strength, power, endurance, and flexibility; relaxation and body composition—that allows optimal and efficient performance of daily and leisure activities.”27 Many health promotion efforts incorporate aspects of prevention. The Guide defines prevention as activities that are directed toward the following27:

• Achieving and restoring optimal functional capacity

• Minimizing impairments, functional limitations, and disabilities

• Maintaining health (thereby preventing further deterioration or future illness

• Creating appropriate environmental adaptations to enhance function.

The Guide goes on to describe three types (levels) of prevention incorporated into the physical therapists practice; primary, secondary, and tertiary (Box 15-2).

Box 15-2 Three Levels of Prevention

• Primary prevention involves using health promotion strategies to avoid disease, before it occurs, in a susceptible or potentially susceptible population.

• Secondary prevention includes efforts to decrease the impact of existing disease states through early diagnosis and intervention.

• Tertiary prevention works to slow down or limit the degree of disability for persons with chronic and irreversible diseases.

A variety of strategies are used to foster health promotion. Health education is any combination of learning experiences designed to facilitate voluntary adaptations of behavior conducive to health.28 A related activity is consultation; rendering professional or expert opinion or advice.27 Finally, health promotion can be provided through advocacy or organized activism related to a particular issue—in this case, improved health for target populations. Taking a comprehensive approach to health promotion would involve integrating all these activities into one’s professional duties.

As explained by Green and Kreuter, health promotion can be delivered at the individual, group, or community level.21Community can be defined as a group of people with diverse characteristics who are linked by social ties, share common perspectives, and engage in joint action in geographic locations or settings.29 As such, a community can be described in terms of such diverse characteristics as geography, race, age, gender, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic status.

Freudenberg and colleagues listed 10 principles of effective health education programs (Box 15-3).30 These principles can also be applied to all health promotion initiatives. The principles are designed to build the capacity and guide actions of individuals and communities to promote health and prevent disease. Note that the key element in these principles is active participation from the target audience in planning, implementing, and maintaining health promotion programs. Reviewing these principles gives the therapist a sense of the skills needed to engage in community health promotion.

Box 15-3 Principles of Effective Health Education

1. Tailor to a specific population within a particular setting

2. Involve the participants in planning, implementation, and evaluation

3. Integrate efforts aimed at changing individuals, social and physical environment, communities, and policies

4. Link participants’ concerns about health to broader life concerns and to a vision of a better society

5. Use existing resources within the environment

6. Build on the strengths found among participants and their communities

7. Advocate for the resources and policy changes needed to achieve the desired health objectives

8. Prepare participants to become leaders

9. Support the diffusion of innovation to a wider population

10. Seek to institutionalize successful components and to replicate them in other settings

Community health promotion and health care professionals

Although addressing the chief medical complaint is most frequently the primary focus for the health care provider, activities that promote a healthier lifestyle are increasingly apparent in the day-to-day practice of most health care professionals. Although most health care providers provide the bulk of their services in the clinical setting, many are also providing health promotion in the community. A 1998 Pew Health Professions Commission Report advocated the inclusion of such activities.14 The Commission proposed the characteristics and needs of the health care system of the 21st century that clearly speak to promoting health at the community level. They include the following:

• Incorporating the multiple determinants of health into clinical care

• Improving access to health care for those with the unmet health needs

• Partnering with communities in health care decisions

• Rigorously practicing preventive care

• Integrating population-based care and services into practice

• Working in interdisciplinary teams

• Balancing individual, professional, system, and societal needs

• Advocating for public policy that promotes and protects the health of the public

These concepts are further supported in the more recent Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice.16

Helvie compared and contrasted the differences between clinic-based and community health practices in nursing.31 This comparison has been adapted for physical therapy services as shown in Table 15-2. In nursing professional education, alternative settings are commonly used for community health clinical experiences. These sites include public health agencies, schools, adult day care senior centers, neighborhood clinics, occupational health centers, social service clubs for boys and girls, hospices, homeless shelters, child day care centers, and day care centers for special needs children. Similar examples of alternative clinical education settings for physical therapy students are also becoming more common.

Table 15-2 Differences in Clinic-Based Physical Therapy and Community-Based Physical Therapy

| Clinic Based | Community Based | |

|---|---|---|

| Unit of service | Individual focused; hospitalized patient | Community groups and subgroups specific to age, health problem, condition, or setting |

| Activity focus | Treatment of disease, short-term intervention for restoration of health | Multiple focuses: health promotion, screenings, rehabilitation, and consideration given to socioeconomic and cultural factors that affect health conditions |

| Range and variability of work | Works with disease classifications, acutely ill patients | Works with entire spectrum of health and illness, all settings, all ages |

| Boundaries of service | One institution, treatment, and recovery | All institutions (e.g., schools, industries) |

| Coordination | Within the institution | Between a variety of medical and nonmedical personnel |

| Legal and medical authority | Institutional policy and state practice acts; always under medical care; diagnosis and treatment orders from referring physician provide framework for care | Health officer, health regulations and laws, and political jurisdiction; frequently no medical diagnosis from referring physician; services obtained through multiple public agencies |

| Autonomy | Physician is medical authority, workload regulated by admissions | Medical management and authority shared by multiple professionals |

| Family and patient autonomy | Individual autonomy of patient is restricted and must fit into institutional routine | Complete autonomy and control |

| Predictability of events | Treatment of patient in one time and place | Interplay of home environment; social, physical, and emotional climate; cultural background |

Several articles have been published related to the role of the primary care physician in community health. Study results suggest that physicians are inconsistent in promoting physical activity with their patients.32–34 These studies suggest that although most physicians ask their patients about their exercise habits, significantly fewer actually counsel their patients about exercise and rarely assist them with exercise prescription. Also concerning, surveys have found only a small percentage of physician participants were familiar with the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) recommendations for exercise. More recently, however, theory-based health promotion intervention strategies are being promoted among physicians in hope of positively influencing the adoption of healthier lifestyles with their patients.35

Referring to occupational therapists, Baum and Law36 point out that, because of changes in the U.S. health care system, practitioners must focus on the long-term health needs of clients so that clients can develop healthy behaviors and thus minimize the health care costs associated with disabling conditions.36,37 They state, however, that doing so requires a shift in thinking from a biomedical to a sociomedical framework and taking an active role in building health communities.

In response to the need for more professionals to address these issues, several certifications have been designed. Certified Health Educator Specialists (CHES) are health educators who have met the standards and passed the CHES examination established by the National Commission for Health Education Credentialing (NCHEC).38 They have skills and knowledge in the following areas: performing needs assessments of individual and community health education and planning, implementing, and evaluating research on effective health education strategies, interventions, and programs. In addition, they serve as resources and advocates for health and health education. They work in various settings, including schools, governmental agencies, and health care facilities. Their titles range from patient educators, to health coaches, to community organizers, to public health educators and managers.

The ACSM and the National Center of Physical Activity and Disability (NCPAD) have recently developed a specialty certification entitled the Certified Inclusive Fitness Trainer (CIFT).39 The CIFT is a fitness professional who conducts assessments and develops and implements exercise programs for persons with physical or cognitive disabilities who are medically stable to perform independent physical activities. A CIFT has knowledge of exercise physiology, exercise testing, programming, and inclusive facility design and awareness of social inclusion for people with disabilities and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). The CIFT is trained to lead safe, effective, and individually adapted methods of exercise and understands precautions for persons with particular disabilities.

Physical therapist’s role in community health promotion

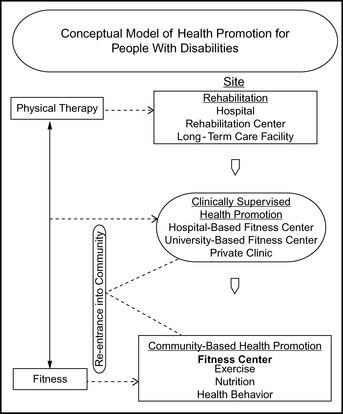

Physical therapists have much to offer to address community health, health promotion, and disease prevention efforts in the United States and globally. As early as 1970, Helen Blood wrote about the importance of developing community health content in physical therapy educational curricula.40 Over the ensuing years, however, physical therapist education and practice continued to be concentrated primarily on curative approaches for their patients’/clients’ chief movement complaint, with less attention paid to health promotion and community health. In 1999, Rimmer called for a greater emphasis to be placed on community-based health promotion initiatives for people with disabilities.41 He charged all rehabilitation professionals to participate in these initiatives but highlighted the physical therapist’s role as an important collaborator, educator, researcher, and program provider for individuals with disabilities. His conceptual model of health promotion for people with disabilities illustrates how physical therapists must extend their services beyond the clinical setting into community-based fitness centers (Figure 15-1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree