Chapter 46 Communication devices and electronic aids to activities of daily living

Various forms of assistive devices and equipment have become part of the daily life of most, if not all, people with disabilities. These devices can allow persons with a disability to participate in activities that otherwise may not be available to them while decreasing dependence on caregivers. They can encourage participation in community or social activities that increase quality of life. They facilitate participation in vocational opportunities that allow for economic self-sufficiency. Assistive technology (AT) can help persons with a disability to live independently rather than in a long-term care facility. Patients who are independent with a given activity when using equipment (as opposed to requiring assistance) have been noted to experience higher levels of autonomy and self-sufficiency.36 Two studies have found that equipment was the most efficacious method of reducing and resolving limitations35 (over assistance from caregivers or other people). This chapter addresses equipment options for basic self-care through high-level community, leisure, or vocational pursuits.

Clinical team

Clients who have significant difficulty with verbal communication will benefit from augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) (as discussed later in the chapter). A speech and language pathologist who specializes in AAC can be a valuable member of the team to address this area. They also may play a significant role in remediation/compensation of cognitive deficits that can impact use of technology.

Funding issues

For many lower-cost items, some clients will be required to pay out of pocket. Otherwise, alternative funding can be investigated. Some hospitals fund equipment from a charity care fund. Clients with certain diagnoses may be able to acquire funding through organizations dedicated to that diagnosis. Pediatric clients may be eligible for benefits through a variety of charitable organizations. Some clients may belong to community groups or churches that maintain or can raise funds to meet some of these expenses. Some U.S. states maintain programs for clients with disabilities to purchase adaptive telephones. For higher-cost items, some clients may qualify for low-interest loans through state AT programs.

Equipment options

An occupational therapist is versed in the use of many lower-technology options that assist with basic or complex ADL. Many larger rehabilitation hospitals have a number of these devices available for trial and resale. These hospitals may offer an ADL apartment that provides clients with an opportunity to trial these devices prior to purchase. Clients who do not have access to these services may be able to find more information on the Internet from vendors, suppliers, and other web sites dedicated to the consumer of assistive devices (see resource list37).

Basic self-care devices

Self-feeding

Mobile arm supports (MAS) are used by persons with limitations in shoulder movement and for feeding. The MAS is a portable device that can attach to a wheelchair It helps with hand-to-mouth movements by assisting with raising the arm against gravity. Several adaptations with the MAS allow clients to more adequately obtain food with their utensil, raise the utensil to their mouth, and reach for a cup. Combined with the proper adaptive feeding devices and splints, many clients with quadriplegia or other upper extremity dysfunction require only setup with a MAS to feed themselves. Clients using a MAS will require minimal shoulder flexion/abduction and minimal elbow flexion to allow for successful use (Fig. 46-1).

Upper extremity dressing

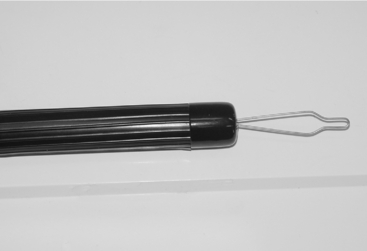

Most clients with significant bilateral upper extremity dysfunction probably are not able to participate physically (with orthoses or not) with their dressing. They can and should be active participants through direction of the task. However, those who have adequate function in one arm will benefit from adaptive methods to don their clothing. Hook-and-loop fasteners can be used in place of standard buttons or ties. An orthosis such as a button hook with a zipper pull can allow people to access buttons and zippers with one hand. It can benefit clients with impaired grip (Fig. 46-2).

Toileting/bathing

Many appliances are useful for toileting. Clients with limited reach may be able to use tongs for perineal cleansing. Similarly, clients with limited reach may benefit from a long-handled sponge or brush for washing their feet or other areas. Some people will consider using a bidet for cleaning themselves. An elevated toilet seat can allow standing or sitting with greater ease. Clients with limited mobility may benefit from use of a male urinal or a freshette (www.freshette.com) for women. A bedside commode can facilitate clients toileting themselves in a timely manner as opposed to use of a standard toilet in another room.

Safety during bathing and toileting should always be addressed. Bathroom safety devices as addressed have been demonstrated to decrease the risk of falls and injuries in elderly people.4 Bathtub transfers have been noted as one of the most difficult transfers for seniors. This can be an even greater challenge for persons with a mobility deficit due to disability. A well-placed grab bar or tub seat can help prevent potentially serious falls for all people but even more so for persons with a disability. Despite the safety advantages offered by access to bathing and toileting aids, these devices are woefully underutilized. Naik and Gill28 found that only 54% of people with a disability related to their bathing had access to bathing aids that could facilitate function and enhance their safety.

Home/office work

Reading

Clients who are unable to hold a book or other reading material may benefit from a number of devices. A book holder with an elastic string can hold pages in place while other pages are being turned. Clients unable to reach a book holder may be able to use a mechanical page turner. These devices can be accessed by either switches or joysticks to activate a combination of rollers and a sticky substance to allow the page to be grabbed and turned. These devices usually are expensive and can be unreliable for certain kinds of books or magazines. If clients are unable to look down (i.e., cervical spine is immobilized), they may benefit from use of prism glasses, which reflect light at a 90-degree angle and allow clients to read a book in their lap. Clients with low vision may benefit from book magnifiers that use external screens or closed circuit television systems that allow for contrast of text on anything from books to bills to prescriptions labels. A number of books are available for reading on a computer (given consistent access to the computer as described later). Commercially available books frequently are available in electronic format designed for reading on a computer screen. Many books that are past their copyright are available for free downloading, and some web sites for downloading copyrighted books are designed for people with disabilities.34

Telephone access

A variety of telephones can assist persons with placing and receiving calls. Clients who cannot hold a standard telephone (because of impaired grip) can use a built-up handle or palm hook on the receiver. A speakerphone or a telephone with a headset can allow for access. Clients who have difficulty with hitting multiple buttons to dial in a timely manner can use speed dial functions. A cordless phone can be used by clients if access is needed from the bed or other areas. Cellular telephones are readily available for the same purpose. People who need more features than the readily available commercial options may benefit from other options discussed later in the chapter.

Call systems

Clients can use a variety of call systems. Clients who are nonverbal may benefit from use of a hand bell or other device. If clients need a device that will sound for farther distances, a wireless doorbell available at most hardware stores may work. Clients activate the button to sound a doorbell placed in a central location where the caregiver can hear it. If clients with limited upper extremity function cannot push the small button, then they may benefit from a personal pager.7 This device allows larger buttons such as switches (see section on switches) to activate a pager. Some clients who can manipulate an intercom can call for assistance. An intercom can be latched on or a baby monitor can be used; however, many people prefer other options so that they do not have to listen to the client’s activities (e.g., telephone conversations or television shows).

If clients are alone during the day, they need a system that allows them to summon assistance from outside the home. Clients who can operate a cordless phone can attach one to their wheelchair with hook-and-loop closure. If clients are at risk for falling while alone, a button worn as a pendant or wristwatch can be used to activate an emergency call system. A monitored emergency call system will contact a 24-hour monitoring service. The service will automatically receive the call along with previously provided information about the client’s condition and contact numbers. Clients who can speak to the monitoring service (with the included speaker phone) can instruct the service to take appropriate action (call neighbor, call 911, etc.). If clients are unable to speak, the service will follow a prearranged plan. Some studies have found that use of an emergency call system can decrease utilization of hospital days and increase the amount of time that elderly persons can remain in the home (as opposed to a long-term care facility).19 If clients are physically unable to push the pendant, alternate switches can be used (see section on switches).

Meal preparation

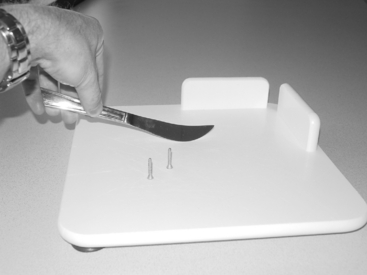

A variety of options allow clients to prepare their meal more efficiently. Stoves with dials on the front can be reached by persons in a wheelchair (as opposed to dials located above the stove). A wooden push–pull stick can be used to extend reach when pulling oven racks in and out of the oven. A rope or cord attached to a refrigerator door handle can be used to pull open the door. Clients who are ambulatory may benefit from a rolling cart that can be used to transport items from the stove or refrigerator to a countertop or dining table. Clients who already are using a walker can use a walker tray or basket (Fig. 46-3), although they must be educated to not overload the tray and possibly unbalance the walker. A variety of tools are available to assist persons having limited upper extremity function with food preparation. Cutting boards with a spike protruding up through it will hold food in place so that persons using one hand can cut or chop the food. Other cutting boards come with a variety of stabilizers to hold food in place (Fig. 46-4). A variety of jar openers allow persons with a weak grip to use stronger forearm pronators and supinators to open a tight lid.27 Electric can openers, food processors, and blenders can reduce energy expenditure and time. Clients may prefer to use a microwave oven for food preparation given the decreased time and ease of use over a standard oven. People who have reduced sensation may need protective equipment to prevent burns from a stove or hot containers.

Higher-technology options

Other team members who may be involved are rehabilitation engineers. Rehabilitation engineers have specific training in biomedical sciences that allows them to match, modify, or create technology to assist clients to perform a given task. A rehabilitation engineer may be involved in making custom devices that allow clients to access paperwork and multiple office documents through a motorized rotating shelf. They may be involved in working with a wheelchair modification that allows clients to more effectively transport a laptop or portable communication device. Ambulatory clients may benefit from a custom carrying case that will allow them access to a device while they are standing and walking. A cellular phone headset can be modified to allow clients with limited hand function to activate the speech recognition features to place or answer calls. Although some of these products are commercially available, a rehabilitation engineer may be able to provide the custom “tweaking” to make a device truly functional for a given client.

Closing The Gap is an organization that addresses AT needs and is designed for consumers and their caregivers. They have an online database of AT products and a large bulletin board system for exchange of ideas. The California State University at Northridge and Closing The Gap offer a yearly conference with presentations related to AT and large vendor exhibits. Abledata maintains a web site (www.abledata.com) that contains reviews, purchase options, and other information related to all types of assistive devices. It is notable for its inclusion of products related to leisure activities and a variety of articles related to consumer information for people with disabilities.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree