Common Pedal Prominences

Thomas F. Smith

Leslie B. Dowling

Osseous and soft tissue prominences or bumps about the foot and ankle represent common patient concerns that can vary from pain to worry about the possibility of a tumor. Inadvertent bumping, irritation from shoes or straps, proximity to stirrups or bracing, as well as various work and leisure activities can all result in significant discomfort for the patient with foot or ankle, osseous or soft tissue prominences. Bony and soft tissue prominences of the foot and ankle can represent arthritic spurring of joint margins, malunited fracture fragments, accessory bones, malformed bones, malaligned bone structures, as well as irritation and thickening of the overlying soft tissues including bursa or ganglion formation. Clinical symptoms of the more common pedal prominences can be the result of pain about the prominence itself or irritation and damage to the intervening soft tissues including the skin, tendons, and nerves. Simple surgical resection of the bony prominence with soft tissue remodeling can many times provide satisfactory resolution of symptoms with little risk for complications. However, complications can arise when an inaccurate assessment results in a poor understanding of why the prominence is present and why it hurts. Foot deformity resulting in prominent normal joint contours would be little aided by surgical remodeling. Joint arthrodesis combined with resection of periarticular bony prominences may help not only reduce the prominence but prevent recurrence as well. Involvement of the surrounding soft tissues by preoperative irritation or intraoperative surgical injury or both can result in either a continuation of pain or new onset pain postoperatively.

Some of the most common osseous and soft tissue prominences of the foot occur at the medial and dorsal aspects of the midtarsal region (1). Painful prominences on the medial midtarsal area of the foot may involve the talus, the navicular, or a combination of both. Medial midtarsal prominences can not only involve an enlargement of the navicular tuberosity but also include accessory ossicles associated with the navicular. If a navicular prominence presents with pes valgus, then combination talus and navicular medial prominences may coexist. Painful medial prominences involving the talus are seen in the pes valgus foot type associated with such conditions as posterior tibial tendon dysfunction, subluxation of the talus, equinus, traumatic tendon rupture, ligamentous laxity, and various neuromuscular imbalances (2). Prominences may present on the dorsal aspect of the midfoot isolated to the first metatarsocuneiform joint (MCJ) or at multiple dorsal midtarsal joint margins as painful exostoses. These dorsal foot prominences are often related to an arthritic process such as osteoarthritis or traumatic arthritis, hypermobile first ray associated with hallux valgus, or a systemic disease processes such as Charcot arthropathy or rheumatoid arthritis. Because the dorsal midfoot has very little subcutaneous tissue, nerve and tendon irritation between the prominence and the shoe can result in neuritic pain as well as painful long extensor tendonitis. To most appropriately manage dorsal or medial midfoot prominences both operatively and nonoperatively, careful clinical and radiographic evaluation is important to accurately identify not only why they exist but also the causation for the pain.

MEDIAL MIDFOOT PROMINENCES

Pedal prominences over the medial arch area of the foot could include the head of the talus, the tuberosity of the navicular, accessory ossicles, or any combination of both talus and navicular components (1). Pain can result from shoe irritation against the prominence itself, a deep achy soreness within the area of prominence, or irritation of the local soft tissues. Medial midfoot prominences result in not only shoe fit and comfort challenges but difficulties with fitting and wearing the custommolded foot orthoses or ankle bracings utilized in their nonoperative management. The diagnosis of the type of medial midfoot prominence is primarily based on correlating clinical evaluation and foot radiographic findings. Bone scanning can help localize a nidus of inflammation as well as differentiate bone or soft tissue inflammation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to assess the integrity of the medial arch soft tissues such as the posterior tibial tendon can be very helpful in the diagnostic process. Posterior tibial tendonitis with the potential for dysfunction and progressive foot deformity is a critical differential diagnosis, especially in the adult population presenting with medial midfoot prominences. Conservative treatment measures can include custom-molded foot orthoses and ankle bracing, shoe modifications and padding, physical therapy modalities, and topical or oral anti-inflammatory medications. Surgical management varies from simple resection to reconstructive procedures to realign the foot based on the specific osseous structures involved in creating the prominence.

TALAR PROMINENCE

Upon palpation of the medial arch prominence, the head of the talus is typically the entity involved when an exaggeration is noted with pronation and a reduction with supination during tarsal range of motion (1). Subtalar joint motion alters the articular congruity of the head of the talus with the corresponding cup of the navicular (3). Supination of the subtalar joint abducts the head of the talus into a more fully articular

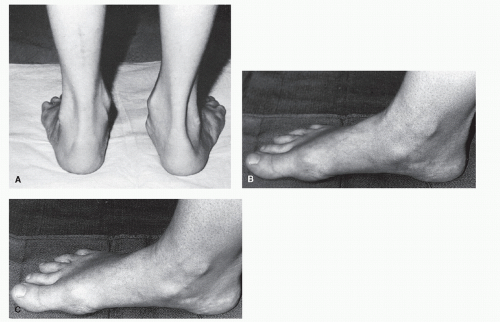

relationship with the navicular as Kite’s angle reduces. This is seen in tarsal supination and certain pes cavus foot types. Pronation of the subtalar joint adducts the talus exposing the medial articular margin of the head of the talus from behind the navicular as Kite’s angle increases. This is seen in tarsal pronation and certain pes valgoplanus foot types. The functional position of the subtalar and midtarsal joints in stance and gait determines the degree of medial talar head prominence clinically and radiographically. The more pronated the subtalar joint, the more prominent the medial head of the talus will become, especially in more transverse plane dominant pes valgoplanus deformities (Fig. 38.1A). Tarsal joint pain, as part of the symptom complex with progressive arthritic degeneration, can be associated with medial talar head prominences. The origin of this type of medial arch prominence is any condition that can result in significant subtalar joint pronation especially in the transverse plane. Congenital pes valgoplanus deformity in the pediatric patient and posterior tibial dysfunction in the adult are common conditions considered in the differential diagnosis. Rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, or Charcot arthropathy may be associated with subtalar joint pronation, adduction of the talus, and medial talar head prominence complaints (4).

relationship with the navicular as Kite’s angle reduces. This is seen in tarsal supination and certain pes cavus foot types. Pronation of the subtalar joint adducts the talus exposing the medial articular margin of the head of the talus from behind the navicular as Kite’s angle increases. This is seen in tarsal pronation and certain pes valgoplanus foot types. The functional position of the subtalar and midtarsal joints in stance and gait determines the degree of medial talar head prominence clinically and radiographically. The more pronated the subtalar joint, the more prominent the medial head of the talus will become, especially in more transverse plane dominant pes valgoplanus deformities (Fig. 38.1A). Tarsal joint pain, as part of the symptom complex with progressive arthritic degeneration, can be associated with medial talar head prominences. The origin of this type of medial arch prominence is any condition that can result in significant subtalar joint pronation especially in the transverse plane. Congenital pes valgoplanus deformity in the pediatric patient and posterior tibial dysfunction in the adult are common conditions considered in the differential diagnosis. Rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, or Charcot arthropathy may be associated with subtalar joint pronation, adduction of the talus, and medial talar head prominence complaints (4).

Nonoperative treatment of medial talar head prominences in more flexible deformities involves foot or ankle orthoses to reduce tarsal pronation and encourage talonavicular congruity. Padding or shoe accommodation of the prominent medial talar head is considered in more rigid deformities. Surgical resection of a medial talar head prominence is rarely indicated to relieve prominence symptoms. The clinical medial talar head prominence problem is not that the talar head is enlarged, but rather the malalignment through tarsal pronation of a normally structured talar head. Partial resection of the head of the talus creates incongruity at the talonavicular joint surface, which can potentiate the development of painful talonavicular joint arthritis. Medial talar head resection is typically only a consideration in a less active patient with a fairly rigid deformity who is unresponsive to nonoperative care and has difficulty with bracing options. Surgical correction of a medial talar head prominence more typically involves procedures to realign and stabilize the rearfoot. In flexible deformities, especially those of younger patients, reconstructive pes valgoplanus-type repairs are employed to address the medial talar head prominence, as well as correction of all components of the pes valgoplanus foot deformity. In more rigid deformities, often found in older patients, procedures such as joint arthrodesis are chosen to realign the foot deformity thus reducing the medial talar head prominence as well as stabilize the joints aiding reduction of associated joint pain (Fig. 38.2).

NAVICULAR PROMINENCE

Palpation of a medial arch prominence that remains relatively constant throughout tarsal range of motion is most likely associated with the navicular and associated accessory ossicles than the talus (4). The navicular medial arch prominence is typically more distal on the arch than the talar prominence, but can overlap the talus medially at the talonavicular joint level and be easily confused with the talus (Fig. 38.1B and C). Radiographic evaluation, particularly the lateral oblique view, helps to confirm that the prominence is the navicular as well as identify the presence of any accessory ossicles. Bareither et al credits Bauhin in 1605 with first describing an accessory bone adjacent to the navicular.

They credit Pfitzer with providing an anatomic description and the nomenclature os tibiale externum or accessory scaphoid (5). Sullivan and Miller (6) cite Geist as the first to study the incidence of the os tibiale externum and to review two possible types of accessory bones by radiographic appearance. The os tibiale externum becomes apparent radiographically at about the age of 9 to 11 years. The incidence of this ossicle in radiographic and cadaveric studies varies from 2% (7) to more than 20% (8). The incidence is evenly divided between men and woman and the condition is typically bilateral in presentation. The os tibiale externum is the second most frequently occurring accessory bone of the foot behind the os perineum and ahead of the os trigonum (9). The accessory bone is known by a multitude of synonyms including accessory navicular, os tibiale externum, navicular secundum, prehallux, bifurcate navicular, accessory tarsal scaphoid, extrascaphoid, and divided navicular. Veitch credits Dwight and later Kohler with developing a classification system that describes three congenital variations of navicular deformity (10). These three types of medial arch pathologies are based on anatomic variations and each specific presentation determines both symptoms and method of surgical correction (Fig. 38.3).

They credit Pfitzer with providing an anatomic description and the nomenclature os tibiale externum or accessory scaphoid (5). Sullivan and Miller (6) cite Geist as the first to study the incidence of the os tibiale externum and to review two possible types of accessory bones by radiographic appearance. The os tibiale externum becomes apparent radiographically at about the age of 9 to 11 years. The incidence of this ossicle in radiographic and cadaveric studies varies from 2% (7) to more than 20% (8). The incidence is evenly divided between men and woman and the condition is typically bilateral in presentation. The os tibiale externum is the second most frequently occurring accessory bone of the foot behind the os perineum and ahead of the os trigonum (9). The accessory bone is known by a multitude of synonyms including accessory navicular, os tibiale externum, navicular secundum, prehallux, bifurcate navicular, accessory tarsal scaphoid, extrascaphoid, and divided navicular. Veitch credits Dwight and later Kohler with developing a classification system that describes three congenital variations of navicular deformity (10). These three types of medial arch pathologies are based on anatomic variations and each specific presentation determines both symptoms and method of surgical correction (Fig. 38.3).

Type I

The Type I navicular deformity represents a small 4 to 6 mm round ossicle proximal to the navicular tuberosity (Fig. 38.3A and B). It is a true sesamoid within the deep substance of the tibialis posterior tendon. This discrete round ossicle is generally referred to as os tibiale externum. It is typically separated from the navicular by 5 to 7 mm. This bone is rarely symptomatic in terms of size and medial arch prominence and does not typically cause irritation with shoe gear. It can become symptomatic if associated with a posterior tibial tendonitis; however, attenuation or thickening of the posterior tibial tendon with resultant compromise to strength and function is more of a clinical issue than the ossicle itself. The os tibiale externum may be a factor in the development or exaggeration of a posterior tendonitis, but its excision alone as a surgical option in such a situation is rarely indicated. Once the ossicle is identified radiographically, especially in the adult with medial arch pain or a medial prominence, MRI can be very helpful in identifying the presence of a posterior tibial tendonitis. The os tibiale externum is not necessarily considered the reason for the pain in this situation, but considered more of a coincidental finding. Surgical interventions for tibialis posterior dysfunction address such concerns as tarsal realignment and tendon repair and may or may not even involve excision of the os tibiale externum when present. Removal of the ossicle itself can be performed as part of the tendon repair process. Simple excision of a Type I accessory navicular may be accomplished by exposing the superior margin of the posterior tibial tendon in the medial arch from the surface of the navicular

distally to the talar neck area proximally. This sesamoid bone is then carefully shelled out from the deep surface of the posterior tibial tendon proximal to the insertion into the navicular. Identification can be difficult if the sesamoid is buried deep within the tendon. If visual inspection or palpation of the os tibiale externum is inconclusive, assistance with the C-arm is helpful to verify the location and avoid damage of the posterior tibial tendon. The insertion of the posterior tibial tendon need not be compromised to effect excision. Surgical exposure of the talonavicular joint is not necessary since the sesamoid does not articulate with the joint. More extensive subperiosteal exposure of the navicular and arthrotomy of the talonavicular joint are indicated if concomitant resection of an enlarged navicular tuberosity is performed in combination with excision of an os tibiale externum.

distally to the talar neck area proximally. This sesamoid bone is then carefully shelled out from the deep surface of the posterior tibial tendon proximal to the insertion into the navicular. Identification can be difficult if the sesamoid is buried deep within the tendon. If visual inspection or palpation of the os tibiale externum is inconclusive, assistance with the C-arm is helpful to verify the location and avoid damage of the posterior tibial tendon. The insertion of the posterior tibial tendon need not be compromised to effect excision. Surgical exposure of the talonavicular joint is not necessary since the sesamoid does not articulate with the joint. More extensive subperiosteal exposure of the navicular and arthrotomy of the talonavicular joint are indicated if concomitant resection of an enlarged navicular tuberosity is performed in combination with excision of an os tibiale externum.

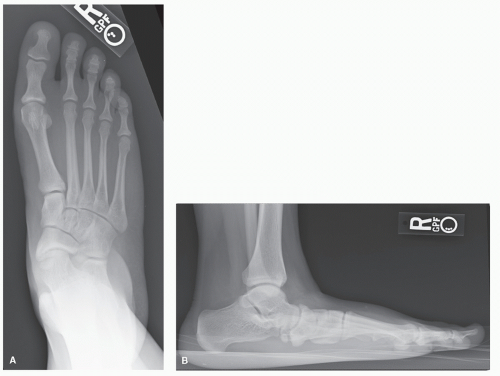

Figure 38.3 Radiographic presentation of navicular prominences. A,B: Type I AP and lateral radiographs. |

Type II

The Type II navicular deformity is a separate ossicle appearing radiographically as an extension of the navicular tuberosity, but connected to it by a radiolucent nonossified zone (Fig. 38.3C and D). This condition is generally referred to as a bifurcate navicular. A Type II navicular deformity presents as a clinical enlargement of the navicular resulting in a medial arch prominence over the tuberosity of the navicular or slightly more proximally overlying the talonavicular joint. The ossicle may be triangular or heart shaped. The radiolucent or nonossified zone can measure 1 to 3 mm and may be fibrous, cartilaginous, fibrocartilaginous, or partially osseous. Lemont et al (11) found this area to represent a true joint within the navicular. Histologic specimens from symptomatic patients simulated microfracture and cellular proliferation suggestive of attempted repair (12,13 and 14). Weight-bearing forces across this area of compromised bone, which is similar to a nonunion, can result in a deep achy type of medial arch pain.

Diagnostic testing can assist in isolating the exact pathology associated with the navicular prominence. The Type II navicular prominence on the lateral radiograph extends rather proximally overlapping the distal calcaneus far more than a normal navicular contour. The size and location of the radiolucent zone within the navicular should be assessed to determine whether the zone is articular or nonarticular with the talus.

CT scanning can help identify the size and shape of the accessory bone as well as the degree of possible talonavicular joint involvement. MRI can be helpful to evaluate for the presence of possible associated posterior tibial tendonitis (15). Bone marrow edema on MRI, as an indication of stress within the navicular, has been demonstrated as a consistent finding (16). This nonossified zone tends to run medial to lateral within the navicular and is typically accompanied by an enlarged navicular tuberosity. In virtually all cases, bone scans show increased activity in painful Type II navicular prominences. This finding was only noted on the symptomatic side in bilateral presentations (13,14,17,18). Patient complaints may include not only medial midfoot prominence shoe irritation but also a deep achy soreness within the navicular itself. If not present preoperatively, resection of a Type II navicular can result in posterior tibial tendonitis and progressive pes valgoplanus postoperatively (19).

CT scanning can help identify the size and shape of the accessory bone as well as the degree of possible talonavicular joint involvement. MRI can be helpful to evaluate for the presence of possible associated posterior tibial tendonitis (15). Bone marrow edema on MRI, as an indication of stress within the navicular, has been demonstrated as a consistent finding (16). This nonossified zone tends to run medial to lateral within the navicular and is typically accompanied by an enlarged navicular tuberosity. In virtually all cases, bone scans show increased activity in painful Type II navicular prominences. This finding was only noted on the symptomatic side in bilateral presentations (13,14,17,18). Patient complaints may include not only medial midfoot prominence shoe irritation but also a deep achy soreness within the navicular itself. If not present preoperatively, resection of a Type II navicular can result in posterior tibial tendonitis and progressive pes valgoplanus postoperatively (19).

Generally, corrective surgery involves excision of the ossicle and remodeling of any enlargement to the navicular tuberosity, combined with supplementary procedures to address any associated pes valgoplanus deformity (Fig. 38.4). Debate exists concerning whether ossicle resection can result in weakness to the tibialis posterior tendon, potentially worsening preexisting pes valgoplanus deformity. Kidner, supported by other early authors, felt this was possible and advocated advancing the posterior tibial tendon following ossicle resection (20,21 and 22). Giannestras noted Type II naviculars in nonpronated feet that did well without tendon advancement (23). Other authors have agreed with this finding noting no advantage to tendon advancement (24,25). There has been no evidence of pes valgoplanus correction with tibialis posterior advancement alone (10,26). If significant pes valgoplanus deformity is present preoperatively with a Type II navicular, it is not unreasonable to include additional procedures to correct or at a minimum prevent progression of the pes valgoplanus deformity following excision. If the foot is relatively rectus preoperatively with a Type II navicular, then advancement of the tibialis posterior tendon to the navicular to maintain functional tension would be a reasonable approach (27,28,29 and 30). The size and extent of the Type II navicular can vary. The nonosseous zone of the ossicle is typically nonarticular with the talus, but it can involve the talonavicular joint. Resection of the nonunion zone with internal fixation without ossicle excision is not unreasonable (31,32). This approach avoids exposing a portion of the talar head that would then be nonarticular with navicular thus protecting and maintaining talonavicular joint congruity. Navicular repair over

resection helps to maintain vital ligamentous insertions that can be compromised with removal of especially larger Type II navicular fragments (Fig. 38.5).

resection helps to maintain vital ligamentous insertions that can be compromised with removal of especially larger Type II navicular fragments (Fig. 38.5).

Figure 38.4 (Continued) D,E: Postoperative AP and lateral radiographs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|