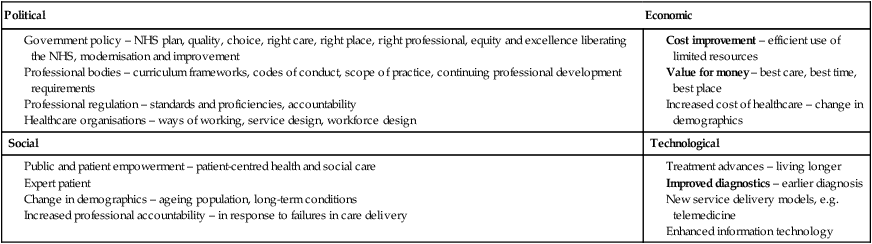

To new physiotherapy students it may seem strange to give prominence to a chapter on interprofessional education (IPE) and team working when they are already convinced they want to be physiotherapists; why would they need to know about other professions? It is well known that students start their professional training with deeply ingrained and historically informed views about what it means to be a particular health and social care practitioner (Hean et al. 2006). However, the inclusion of this chapter, which is new to this edition, signals a change in both professional education and in practice that acknowledges that no one profession can practise effectively in isolation and that a change to a more collaborative way of working is necessary to deliver the best outcomes for clients and service users. In fact, we argue that all practice is collaborative. It is important that students are aware from the outset that IPE is not a taken for granted concept, accepted unconditionally and embraced by all health and social care professions, or even individuals with equal enthusiasm. There has been a long history of concern over poor communication and professional rivalry between disciplines and competing professionals (Cleake and Williamson 2007). Inevitably, this has influenced how health professional education has been delivered and, as a consequence, it has been criticised for being ‘designed and delivered within silos’ (Ramsammy 2010: 134). Research confirms that silo models remain deeply entrenched in places (Barker et al. 2005). We aim to introduce students to the political, social and economic complexities of IPE that have resulted in its patchy implementation. However, we will also explore principles of best practice, different models, the extent of its global spread and point to evidence of impact where it exists. Moving full circle in justifying the focus of the chapter, we conclude by discussing the interface between professional and interprofessional identities. Mhaolrunaigh (2001) suggests that embracing the notion of working collaboratively requires students to reflect on their own profession and professional background, and to then see their own profession in relation to ‘new others’. These are fundamental issues which might seem of a lower priority than the more immediate concerns of proving competence and accumulating the vast knowledge base necessary for contemporary practice. However, rather than compromising uni-professional knowledge, IPE provides the means of adding to a different type of knowledge and confers a different type of capability. Collaborative learning ‘allows students to become members of knowledge communities whose common property is different from the common property of the knowledge communities they already belong to’ (Bruffee 1999: 3). IPE does not detract from the status of the professional; it makes for a flexible and open-minded practitioner capable of working across boundaries and providing collaborative holistic client care. IPE is simply defined as ‘Occasions when two or more professionals learn with, from and about each other to improve collaboration and the quality of care’ (CAIPE 1997). Although professionals may have shared their learning experiences and expertise since formal healthcare was conceptualised, specifically planned and structured opportunities for IPE were not established in the UK until the 1960s (Barr 2007), when the first interprofessional symposium exploring ‘Family Health Care: The Team’ was held in London (Kuenssberg 1967). In the UK, the evolution of IPE has been integrally linked with political change and social growth. Towards the end of the last century it became apparent that many hospital- and community-based services were essentially working in isolation, each with little knowledge of the other’s role, expertise or skills. This absence of communication and liaison between healthcare contributors led to fragmented service delivery and substandard patient care (Barr 2007). These collaborative failures sometimes resulted in tragedy, particularly in child protection (Colwell Report 1974; Laming Report, 2003) and psychiatric aftercare (DH 1994). The factors contributing to poor working relationships between health and social care professionals are extremely complex; many professions had their roots entwined with status, class and gender (Barr 2007), or provide identity to their members, promoting prejudice or professional mistrust (Carpenter 1995). Professional isolation was perpetuated through the use of specialist language or jargon (Pietroni 1992), or keeping individual patient records. Indeed, health and social care students were not only entering their professional training with established prejudice regarding other professions, but qualifying and leaving with their prejudices reinforced (McMichael and Gilloran 1984). This notion raised the possibility of using education to improve interprofessional understanding and successful collaborative working. In 1987, the Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education (CAIPE) was established in the UK. Initially, this charity organisation directed its attention to issues within primary care, but subsequently expanded with interests in local government, higher education and professional associations. The following year, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued a statement which highlighted the theory that if healthcare professionals learned to collaborate as students, these skills would translate to the workplace, facilitating effective clinical or professional team working (WHO 1988). Indeed, throughout the 1980s the Health Education Authority (HEA) launched a series of shared learning workshops throughout England and Wales, focussing on specific patient groups and their problems (Spratley 1990). The concept of collaborative learning was supported by the government white paper ‘Community Care in the next Decade and Beyond’ (DH 1989), which emphasised the importance of ‘multiprofessional training’ and was used in the foundations of the 1990 NHS and Community Care Act (DH 1991). These guidelines stated that ‘joint training’ was an expectation, which must be included in community care plans and training strategies (DH 1991; Barr 2007). The 2001 government white paper ‘Working Together, Learning Together: A Framework for Lifelong Learning for the NHS’ (DH 2001) provided a strategic framework and co-ordinated approach to continued professional development. It stated that ‘core skills, undertaken on a shared basis with other professions, should be included from the earliest stages in professional preparation in both theory and practice settings’. Most early IPE events were small-scale workshops or short courses focussing on aspects of primary or community care (Barr 2007). However, as many royal colleges, professional and regulating bodies pledged support and contributed to IPE evolution, educational initiatives grew in size and commanded increasing interest. Over the last 30 years, IPE has become an established movement. Shared learning between health and social care professionals is now embedded in most undergraduate curricula and continually extends through professional development. Governments continue to issue clear policy to encourage collaborative practice and partnership working, to develop students able to undertake, and contribute to, effective NHS interprofessional working (Finch 2000). The WHO identified IPE as a priority activity in 1984. In 1988, it published a report which drew on examples from developed and developing countries to inform a unifying definition and rationale for IPE (Barr 2009). The report suggested that ‘students should learn together during certain periods of their education to acquire the skills necessary for solving the priority health problems of individuals and communities known to be particularly amendable to teamwork’ (Barr 2009: 17). Since the late 1980s the call for a shift towards collaborative interprofessional practices has crossed international boundaries, inspired by a common goal of reducing health inequalities and improving the health of populations. These ideals were reiterated in the recent WHO Framework for Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Care (WHO 2010). WHO member states, eager to achieve equitable, fair, affordable and efficient care, are increasingly focussing on primary care as providing the most suitable means (Gilbert 2010). This focus is evident in the increase in interest in interprofessional collaboration and in policy commitments around the world, for example the Canadian government’s call for a move towards patient-centred interprofessional primary care (Health Canada 2003). In Japan, where longevity rates are among the highest in the world, IPE as a means of promoting collaborative working is considered essential to promoting quality of life (Takahashi and Sato 2009). Concerns about quality and safety issues in the USA healthcare system has resulted in resurgence in interest in IPE as a means of promoting interprofessional collaboration and reducing patient errors (Ragucci et al. 2009), while IPE in the UK has emerged through a series of government policies aimed at modernising health and social care. A recent edition of the Journal of Interprofessional Care (March 2010) drew attention to the development of IPE internationally, highlighting that notwithstanding additional challenges and resource constraints in developing countries, recognition of the benefits of a collaborative workforce is not confined to Western countries. In 2009 the WHO established the Health Professionals Global Network with the aim of maximising the potential of all health professionals through a virtual network, fostering interprofessional collaboration and contributing to the global health agenda (see http://hpgn.org/). In 2010, the network held a global consultation on IPE and collaboration, and more than 1000 delegates from 97 countries participated (Gilbert 2010). The recent Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice (WHO 2010) captures a sense of IPE practices at a global level. Representatives from 42 counties provided insight into practices from practice, administration, education and research perspectives. The findings of the scan show that IPE occurs in ‘many different countries and health care settings across a range of income categories’ (according to the World Bank’s Income Classification Scheme) and ‘involves students from a broad range of disciplines including allied health, medicine, midwifery, nursing and social work’ (WHO 2010: 16). Physiotherapy students in a wide range of countries can expect to find that IPE is a compulsory aspect of their curriculum at undergraduate level that is mostly delivered using a face-to-face approach, although the use of technology to foster IPE is growing, especially where large numbers of students from several professions are involved. • considering the concept of IPE as integral to your own learning; • exploring how your own practice relates to the concept of interprofessional working; • reviewing how to anticipate and improve interventions carried out by yourself and others; • understanding the importance of current evidence and policy, and how to take forward the learning from a simulated environment into the workplace; • developing the ability to interpret information by the use of student-led interprofessional learning. Having engaged with the learning you should have developed the ability to explore current practice utilising your reflective skills, knowledge and understanding to improve your personal and professional development, and thus enhance delivery of care to the service user in an interprofessional working environment. A good practitioner is, arguably, someone who is always punctual, who is respectful to clients and to other team members, and is considered to be reliable. What is the difference between a good and an excellent practitioner? An excellent practitioner is one who achieves best possible practice. While working through this section you should be considering what makes an excellent practitioner and at the same time reflecting upon your own practice to identify ways to always strive for excellence. There are certain factors that make being a practitioner easier. Physiotherapy students need to develop skills to enable them to work in an interprofessional environment. As well as the interpersonal skills required to work effectively in a range of environments with a range of personnel (at all levels), there is a need to develop confidence, clinical reasoning, evaluation and reflective skills (Smith and Green 2003). In fulfilling the ability to self reflect it is imperative to understand therapeutic use of self, self-awareness and constructive use of feedback. Exploration of these skills will make the application of interprofessional working more feasible. When exploring the literature concerned with IPE, it is evident that there is some confusion over descriptions and definitions. The nomenclature can be confusing, as Barr (2005: xvii) states: ‘interprofessional education is bedevilled by terminological inexactitude’. For the purposes of this chapter, the authors have used the CAIPE (1997) definition of IPE, emphasising learning from, with and about each other. Table 2.1 describes the nomenclature you may find in the literature and/or experience as part of your learning experiences. Table 2.1 Source: Barr (2005). As described in the previous sections, there is no definitive model of IPE; thus, organisations have developed their own models which best suit their organisational contexts and student mix. The Leicester Model of IPE is one example (Lennox and Anderson 2007); for further examples you are directed to the higher Education Academy occasional paper Piloting Interprofessional Education (Barr 2007). Irrespective of how different organisations have implemented IPE they share a common context in which they operate; this section will outline the political, social, economic and technical drivers that underpin the requirement for IPE (Table 2.2). Table 2.2 The imperative to expose pre-registration health and social care students to IPE has, for some time, been directed by a number of policy directives and is not new (DH 2000a, 2000b, 2001, 2009, 2010a, 2010b; Hammick et al. 2002). Since the NHS plan was published in 2000, there has been an increased emphasis on a patient-led NHS and, alongside that, the requirement for IPE to be an integral part of education and training programmes. UK health professional regulatory bodies also demand the inclusion of IPE in all professional curricula (NMC 2004; HCPC 2004). Within higher education, the quality assurance of health and social care education has as a central tenet the requirement to demonstrate where and how IPE is being taught within pre-registration curricula (QAA 2006). Recent policy documents (DH 2000a, 2000b, 2001, 2006, 2009, 2010a, 2010b) re-emphasise the continuing drive towards an agenda of modernisation and improvement in health and social care services, predicated upon the view that interprofessional working is key to its success. Also, the political imperative to ensure continual service improvement cannot be achieved without professionals working together: ‘if we are to achieve the aim of health care teams continuously improving the quality of care they provide to their patients, we need to deepen our understanding of what is needed to enable them to work and learn together’ (Wilcock et al. 2009: 88). As Davidoff and Batalden (2005: 80) suggest, ‘the ideal conditions for achieving this are when everyone working in health care recognises that they have two jobs when they come to work every day, to do their work and improve it’. In addition, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) supports the notion of creating a more flexible workforce that can operate across boundaries and promote partnerships (www.nice.org.uk). Failures in traditional care delivery have contributed to the call for greater collaboration of healthcare professionals. Examples such as the Bristol Royal Infirmary Inquiry (DH 2001), the Victoria Climbie Inquiry (Laming Report 2003) and, more recently, Baby P (Laming 2008) highlight the fact that uni-professional working may hinder optimum care while interprofessional working may help to avoid these failures. These very public failures have led to an increased scrutiny of health and social care professionals, with increased accountability. The demographic changes in the UK population – an increasingly ageing population and people living with long-term conditions as a result of improvements in diagnosis and treatment advances – has led for a call for healthcare professionals to work across traditional boundaries and create inter-agency partnerships, all requiring improved collaboration between professional groups (Wanless 2004). Within the Allied Health Professions (AHP) the publication in 2000 of the ‘Meeting the Challenge: A Strategy for Allied Health Professions’ document further emphasised the importance of collaboration and cross-boundary working outside of traditional uni-professional silos. Although primarily concerned with describing the changes in the roles of AHP within contemporary healthcare, one of the strategy’s main tenets called for undergraduate education programmes to be more flexible and more patient- and practice-centred via the inclusion of enhanced opportunities for IPE (DH 2000a, 2000b). In 2005, the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC 2012) standards of proficiency under the section relating to professional relationships states that: Registrants need to understand the need to build and sustain professional relationships Are able to contribute effectively as a member of a multidisciplinary team Are able to sustain professional relationships as an independent practitioner Despite all these initiatives around increasing the opportunity for IPE for health and social care students in practice, there is still a lack of substantive evidence that engaging in IPE impacts positively on interprofessional working in practice. In response to this, the Creating an Interprofessional Workforce (CIPW) project was initiated and findings were published in 2007. CIPW provides a strategic framework for IPE and training to underpin collaborative working practices and partnerships (DH 2006). Most recently, the new government published its NHS white paper ‘Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS’ (DH 2010a). Although in many ways this strategy moves away from the previous government’s strategy for the NHS, the imperative for a patient-centred NHS remains a key priority. The main tenets of this white paper are: • services designed around patient’s individual needs, lifestyles and aspirations; • giving citizens a greater say in how the NHS is run; • strengthening the collective voice of patients by creating Health Watch England; • shared decision-making – ‘no decision about me without me’; Over the past 10 years, the modernisation of the NHS has seen a significant cultural shift in the way that healthcare is delivered, requiring healthcare professionals to work in very different ways. Prior to the modernisation movement, healthcare was essentially profession-led, where professionals made decisions about patients for patients. The shift away from profession-focussed care to one where patients and the public are empowered to make decisions and choices in relation to their healthcare has required professionals to work in different ways. No longer is it acceptable for professionals to exist in professional silos. Service modernisation has resulted in service delivery models that are predicated upon care pathways and not profession focussed pathways. Practitioners increasingly work in multi-professional teams associated with a specific care pathway (e.g. long-term conditions, stroke, cancer, end of life, musculoskeletal) as described in the National Service Frameworks (DH 2006). The list below provides a checklist of the publications that outline the major drivers: World Health Organization (WHO) 1988 Learning Together to Work Together for Health 2010 WHO Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice 2000 A Health Service of All the Talents: Developing the NHS workforce 2000 The NHS Plan: A plan for investment, A plan for reform 2000 Meeting the Challenge: A strategy for the Allied Health Professions 2001 Working together, learning together 2003 The Victoria Climbie Inquiry: Report of an inquiry by Lord Laming 2004 The NHS Knowledge and Skills Framework and the Development Review Process 2006 Our Health, Our Care, Our Say 2007 Creating an Interprofessional Workforce 2008 Allied Health Professions Competence Framework 2008 High Quality Care for All: NHS Next Stage Review 2010 Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS 2010 Equity and Excellence: Developing the NHS workforce 2010 Equity and Excellence: Public Health Paper Professional, Regulatory and Statutory Bodies 2006 HCPC standards of proficiency IPE provides the vehicle for students to: • gain an understanding of the complexity of interprofessional health and social care delivery; • develop and practise team-working skills (communication, negotiation, value, respect, collective decision-making, joint goal-setting and outcome measurement); • be prepared for working across traditional boundaries; • practise their own professional role within the context of the wider healthcare team in a secure learning context where mistakes will not have real life consequences; • test out and reflect upon their own professional knowledge, skills and values against others; • test out negotiating skills around professional boundaries and learn about/from the difficulties inherent in the process. It can be argued that one of the most important lessons for you as undergraduates to take away from your experiences of IPE is the recognition that no one individual professional or distinct professional group can meet all the health and social needs of individuals requiring health and social care intervention. In order to contribute to the improvement of health outcomes for their patients, today’s practitioners must be able and willing to work collaboratively, knowing when they have a contribution to make and, importantly, when they do not and therefore seek help from colleagues. IPE provides real opportunities for undergraduates and postgraduates to learn with and from each other in ways that uni-professional learning will never be able to do (Bokhour 2006; Lennox and Anderson 2007; Barr 2007). Learning together is never easy; students studying specific professional programmes commence those programmes with well-formed constructions of the professional they are learning to become. This can make learning together a difficult process. It is never easy when cultures collide (Jenkins 2004). IPE can provide an opportunity to improve understanding of self; Chambers (2009) suggests that during interprofessional exchanges students test out their emerging professional identity as a way of working out what they are not in order to work out what they are. She suggests that IPE is pivotal in the process of constructing a particular professional identity. A number of significant political and societal and professional changes have taken place over the past ten years and continue to do so. These influence how health and social students are prepared for a career likely to span 40 years. The changes as described above have had a major influence on the education and training of healthcare professionals as educators are charged with ensuring health and social care graduates are equipped to be effective practitioners in a complex, ever-evolving health and social care system. Educators are required to prepare graduates who are fit for practice and fit for award. The patient and public empowerment agenda continues to be a priority. In order to attend to this, healthcare professionals will need to practise in ways that empower patients to be partners in their own care (DH 2009). Remember … … ‘No decision about me without me’ (DH 2009).

Collaborative health and social care, and the role of interprofessional education

Introduction

History of interprofessional education (IPE)

Is IPE an international phenomenon?

The IPE context within the UK

Term

Learning

Multi-professional

Learn side-by-side

Interprofessional

Learn with, from and about each other

Shared learning

Learn alongside each other with NO interaction

Common learning

Learning a common curriculum

IPE and collaborative working