Chapter 10 Clinical Problem Solving

Making Clinical Decisions

To make sound clinical decisions, the clinician must first check his or her mindline. If there are knowledge gaps in the mindline, it can be updated by asking a focused clinical question and using the techniques of evidence-based medicine. Next, the clinician discusses potential risks and benefits of treatment options with patients, determining their preferences. By integrating the medical evidence with patients’ preferences, a shared clinical decision is reached.

Focusing the Question

Finding the Evidence

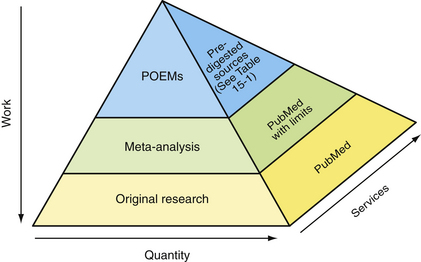

As shown in Figure 10-1, the work required to find useful medical information is inversely proportional to its quantity. At the bottom of the pyramid is original research. Although plentiful, much of it represents “medical chatter” among researchers (Slawson et al., 1994). Researchers are intimately familiar with published data in their narrow field of study and are able to place the article in its proper context. A busy clinician reading a single article in a relatively unfamiliar field is akin to overhearing a snippet of conversation at a dinner party. It may be dangerous to base decisions on such snippets without knowledge of the larger context. Checking the relevance and validity of such studies requires knowledge of statistical methods and study design. It is too time-consuming to be useful for answering clinical questions that arise during a patient visit.

At the peak of the pyramid are patient-oriented evidence that matters (POEM) reviews (Table 10-1). Clinicians must decide if the POEM is relevant to their clinical question, but the amount of work required is greatly reduced. POEMs offer the most useful type of information for answering clinical questions that arise during patient visits. Unfortunately, a POEM does not exist for every clinical question. In these cases the clinician must step down the pyramid until relevant information is found.

Table 10-1 POEM∗ Sources

| Source | Website |

|---|---|

| Free | |

| Bandolier | www.jr2.ox.ac.uk/bandolier |

| Cochrane Abstracts | www.cochrane.org/reviews/index.htm |

| National Guidelines Clearinghouse | www.guidelines.gov |

| Subscription | |

| American College of Physicians | www.acpjc.org |

| Clinical Evidence | www.clinicalevidence.org |

| Cochrane Reviews | www.cochrane.org/reviews/index/htm |

| Family Physicians Inquiries | www.fpin.org |

| Network InfoRetriever | www.infopoems.com |

| Journal of Family Practice | www.jfponline.com |

| Up To Date | www.uptodate.com |

∗ Patient-oriented evidence that matters.

Haynes (2001) defined another pyramid that is relevant to answering clinical questions. This is the pyramid of services for finding the best evidence. It is depicted as the third dimension of the evidence pyramid (Figure 10-1). At the bottom of the pyramid are tools to find the original studies. The National Library of Medicine maintains a database of more than 15 million articles, called MEDLINE. Various engines are available to search MEDLINE and other databases for articles that may be used to answer clinical questions. For example, PubMed (www.pubmed.gov) provides tools to help clinicians search for meta-analyses and systematic reviews through the use of limits and clinical queries (Ebbert et al., 2003; Haynes and Wilczynski, 2005; Sood et al., 2004).

As in Mrs. Smith’s case, there may not be a single study that addresses the specific question posed. In looking for the best evidence to inform clinical decision making, it is important to determine the standard of care for the patient’s condition. Clinical guidelines, which are typically updated every 2 years, may be a useful resource. An excellent clearinghouse for clinical guidelines is sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ, www.guidelines.gov), although the listed guidelines are neither reviewed nor endorsed by AHRQ. Clinicians must critique the guidelines for validity and relevance in their own setting. This resource is higher up the services pyramid and reflects some interpretation and synthesis of original research and clinical practice.

You review the Institute for Clinical Systems Integration guideline for osteoporosis prevention and HRT at www.guidelines.gov, as well as the risk/benefit data from the www.WHI.org site (Figure 10-2). These guidelines tell you that HRT should not be used simply for prevention of osteoporosis in the absence of other significant menopausal symptoms. You reflect on your colleague’s words: “Get everyone off that stuff!” It is time to have a discussion with Mrs. Smith regarding her estrogen therapy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree