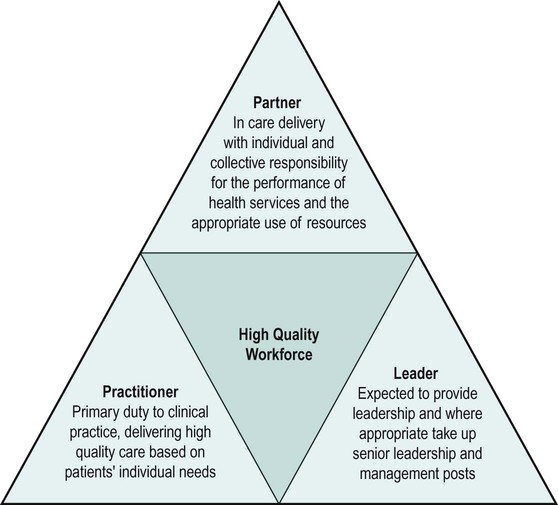

While the need for strong and effective leadership in healthcare is well recognised there is still the need for ongoing exploration of how leadership in healthcare contributes to improving health outcomes (Hardacre et al. 2010). Work by Hardacre et al. suggests that leadership for improvement is culturally sensitive, inclusive, team-based, personal and collective (p. 27). There is, however, a growing body of evidence that links leadership, culture in organisations and improved outcomes and quality (Corrigan 2000). Research into nursing leadership (Edmonstone 2011) suggests a direct link between effective nurse team leadership and the quality of team work. In essence, effective leadership is seen as essential to improving health outcomes. National Health Service (NHS) organisations have and continue to invest significant amounts of resources to developing existing and aspiring leaders, and leadership competence in healthcare. Work by Hardacre et al. (2010) suggests that some leadership behaviours appear to be positively associated with service improvement work and that service improvement work is beginning to show links to improved health outcomes. Narrative research utilises stories as a way of exploring and, therefore, understanding more fully the lived experiences of human beings (Mishler 1990, 1999; Reissman 1997). Leadership narratives are very powerful as a way of understanding human action and interaction. The stories of real leaders doing the very real job of leading NHS organisations have influenced the writing of this chapter. What this chapter does not do is provide the reader with leadership theory. Readers are able to access leadership theory through a wide range of leadership and management textbooks, and readers are directed to Jumaa and Jasper (2005) and Jarvis et al. (2003) as a starting point. Constraints of space and constraints of purpose have allowed the author of this chapter to take a practical approach to the subject, drawing upon published literature but, more importantly, drawing upon real examples of clinical leadership. In this way, the chapter attempts to bring clinical leadership to life and to drive home its importance to readers. By using the NHS leadership qualities framework (LQF) (NHSi 2009) alongside broader leadership concepts, the chapter includes descriptions and illustrations of clinical leadership in contemporary healthcare. It will provide a brief overview of the healthcare reform context (readers are directed to other chapters in this book for more detail), describe, in some detail, the elements of the LQF and, through this, explore some of the implications for today’s physiotherapists. The chapter concludes with some practical advice on how physiotherapists can take personal responsibility for developing their leadership credentials. When reading the leadership literature it is apparent that the concept of leadership is used in a wide variety of ways and tends to be described in behavioural terms (Jumaa and Jasper 2005; McDonald et al 2009; Hardacre 2010; King 2010; Edmonstone 2011). This varied use of nomenclature and definition can be confusing for those new to leadership writings. Put simply, leadership is concerned with individuals and teams achieving what it is they set out to achieve. The leader is someone who provides the focus and sets the direction of travel but achieves an outcome through the collective actions of the whole team. Contemporary healthcare is complex and undergoing the biggest change since its inception in 1948 (DH 2000, 2001, 2008, 2010). Although we all think of the NHS as one big organisation, in reality it is made up of many different organisations, each with its own culture and ways of working. These NHS organisations have been undergoing a radical change programme for over ten years and are currently in the middle of another reorganisation, probably its most radical yet. As the government’s white paper (2010) states, at its best the NHS provides world class care; however, there is still some way to go before world class care is experienced throughout the vast organisation(s) that we call the NHS. Just like any other large organisation in today’s climate of austerity and economic challenge, the NHS is charged with ensuring efficient and effective working, raising standards and redesigning services to improve the quality of the patient experience (DH 2008, 2010). This is a particularly challenging time for the NHS: redesigning services and the workforce that delivers the service, raising standards, and improving efficiencies and real-term savings requires strong leadership. Leadership is not just the responsibility of the most senior managers but the responsibility of all staff, of whatever level, who work within the NHS and who are charged with improving healthcare outcomes (NHS North West Leadership Academy 2008; DH 2008). Also, the creation of a new Public Health Service located within local government rather than as an integral part of the NHS will require professionals to work much more collaboratively, with a greater impetus toward ensuring that multi-service, interprofessional, inter-agency working and collaboration are the norm (DH 2010). Readers are directed to Chapter 2 for more details and references on collaborative working. All organisations need financial investment, technical knowledge, access to a market, political impetus, professional expertise and quality equipment, etc. (NHSi 2009) and the NHS is no different. All organisations need leaders who can utilise resources effectively and efficiently in order to create success (NHS Alliance 2007). Strong leadership creates an environment where success is more likely to happen. The size and scale of NHS reorganisation and proposed health reform creates a highly challenging and complex context. This context creates an environment where many organisations are focussing on identifying and developing existing and potential leaders as a way of effectively leading and managing the reform agenda. Arguably, organisations that survive are those that have a strong focus on leadership development practices and have a shared understanding of what good leadership means (NHS Alliance 2007; McDonald et al. 2009; Towill 2009). A lot of attention has been focussed upon developing individual leaders; Edmonstone (2011) calls for a rebalancing to refocus attention on context and relationships rather than individual leaders, thus emphasising the importance of a collaborative approach to improving services through a distributed leadership model (NHS North West Leadership Academy 2008; NHSi 2009). The Department of Health’s (DH) ‘High Quality Care for All: Next Stage Review Final Report’ and the ‘High Quality Workforce: Next Stage Review Report’ (2008) were two important documents that provided the impetus for leadership development throughout the NHS. These documents put the spotlight on the quality of care provided, as well as the concept of care for all, as a means of ridding the NHS of inequity and inequality of provision inherent in some parts of the system (DH 2008). The most recent white paper continues to emphasise the centrality of the quality agenda in the provision of patient-centred care. The shift to a truly patient-centred health service – ‘no decision about me without me’ (DH 2010: 9) – requires clinicians to rise to the leadership challenge. A ‘High Quality Workforce: Next Stage Review’ (DH 2008) highlighted three aspects of every clinician’s role, now and in the future. These aspects remain relevant today and are likely to remain so for a long time. The three aspects are described as: Practitioner, Partner and Leader. Figure 3.1 describes how each different aspect can contribute to the high quality workforce required to deliver high quality, improved healthcare. The planned NHS reconfigurations as outlined in ‘Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS’ (DH 2010) along with existing NHS service reconfigurations, for example transforming community services and the quality, improvement, prevention and productivity (QUIPP) agenda (DH 2009), provide a context that demands effective leadership. From an Allied Health Professions (AHP) perspective, leadership development is a high priority. The Department of Health Leadership Challenge events (2009, 2010) are testament to this and readers are directed to the DH website for further details (www.dh.uk). Across England there are regional AHP networks all engaged in regional leadership development as a way of framing the contribution of AHPs in delivering a world-class patient-centred service (e.g. www.nhsnw.uk/ahpnetwork). Also, the AHP career framework (Skills for Health 2007), which was created in response to the ‘Modernising Allied Health Professions Careers’ project (DH 2002), emphasises the importance of leadership. The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy’s newly published physiotherapy framework (CSP 2010) includes the knowledge, skills and values required of effective clinical leaders. This framework was the product of a lengthy project called ‘Charting the Future’, and defines and illustrates the knowledge, skills, behaviours and values required for contemporary physiotherapy practice (CSP 2010). This framework not only underpins contemporary practice, it is also the basis from which undergraduate and postgraduate physiotherapy education is developed. It describes physiotherapy practice at all levels, across different professional roles, across a variety of settings and across all four nations of the UK. Readers are directed to www.csp.org.uk for further details. Just as there is a lack of commonality in the use of the concept ‘leadership’, the term clinical leadership is still being defined and refined (Cook 2001; Stanley 2006).As this chapter is primarily about leadership in the NHS, it is useful to provide a definition of clinical leadership. The definition below is useful in that it emphasises the importance of leadership as action rather than as leadership relating to position: The LQF was created specifically to provide a common language and approach for leadership in the NHS (NHSi 2009). It was designed over a two-year period by the Hay Group and launched in 2002 by the then NHS Chief Executive and Permanent Secretary to the Department of Health Sir Nigel Crisp. It was reviewed most recently by the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement (NHSi) in 2006. It is said to reflect the culture of the NHS and is designed to be flexible and intuitive, and allows for individual self-reflection (see Chapter 5 for further details). A widely-available framework, the LQF allows individual clinicians to analyse their own leadership roles and therefore can be a useful self-development tool. The LQF sets the standards for outstanding leadership and describes the qualities expected of existing and aspiring leaders. Within the LQF there are 15 leadership qualities clustered into three groups: Each cluster describes the key characteristics, attitudes and behaviours required for effective leaders at all levels (NHSi 2009). Full details of the LQF can be found at www.nhsi.nhs.uk. This next section will describe each cluster of leadership qualities and relate them to how you may begin to reflect upon your own abilities and strengths, as well as begin to identify your development needs. The descriptions below are adapted from the LQF. A complete version of this can be found at www.nhsi.uk. Readers are also directed to Griffin (2009) for examples of use in practice.

Clinical leadership

Introduction

Context

The allied health professions and physiotherapy

NHS leadership qualities framework (LQF)

Clinical leadership