Chapter 3 Clinical Examination of the Knee

Observation and Inspection

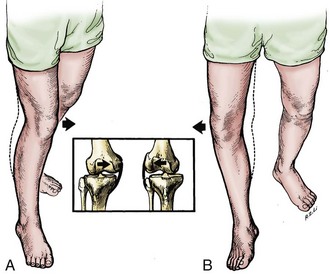

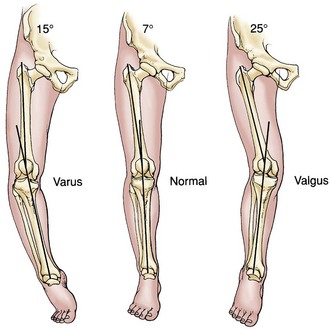

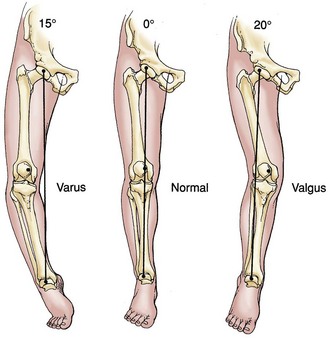

The examination should begin with observation. Observation of the patient’s gait provides critical information. The examiner should note the patient’s ability to ambulate, the use of gait aids, the speed of ambulation, and the amount of discomfort present with attempted ambulation. Evaluation of the gait pattern and the stance position of the lower limb is performed while the patient ambulates. A shortened stance phase of gait (antalgic gait) will confirm the side of involvement. A short leg gait requires confirmation of limb length. This may be accompanied by a significant varus or valgus deformity at the knee or may represent an extra-articular deformity requiring further evaluation. Varus or valgus alignment should be noted, as well as any medial or lateral thrust in the stance phase of gait (Fig. 3-1). The clinical alignment of the lower part of the leg (anatomic axis) measures the femorotibial angle (Fig. 3-2) and is different from the mechanical axis of the limb (Fig. 3-3), as measured from the femoral head through the knee to the center of the ankle on a standing roentgenogram. With a goniometer applied to the anterior aspect of the thigh and the lower part of the leg and centered on the patella, the examiner can report the clinical varus or valgus alignment. This measurement should be used along with the roentgenographic measurements.

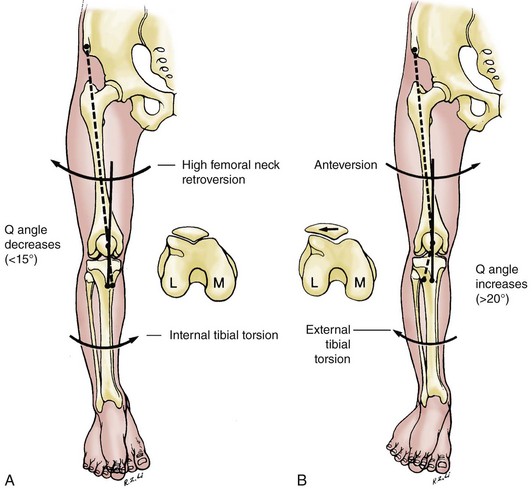

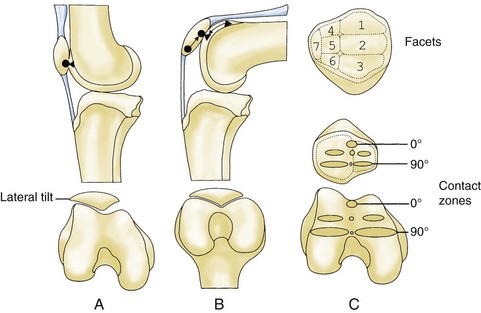

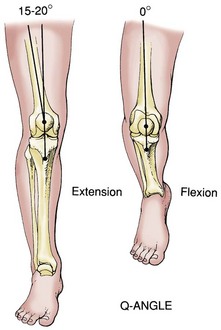

Patellar alignment must also be observed. It is influenced by femoral neck anteversion, tibial torsion, the anatomy of the individual patellar facets, and the depth and angle of the femoral sulcus (Fig. 3-4). The Q angle is drawn from the middle of the tibial tubercle to the middle of the patella and then to the anterior superior iliac spine of the pelvis. The normal angle is 10 to 20 degrees.

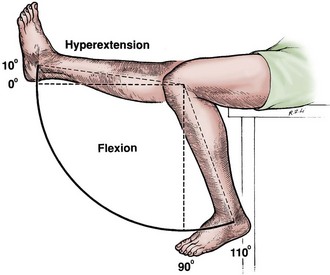

Clinical effusion may be apparent visually. Active range of motion should be recorded, along with any limitations to full extension or flexion. Active range of motion will be further evaluated with palpation and should be compared with passive range of motion of the knee (Fig. 3-5). It is customary that full extension should be considered 0 degrees, and flexion is recorded as an increasing number or as the distance of the heel of the foot from the buttocks. An inability to fully extend may represent lag, a locked knee, or a flexion contracture. An inability to fully flex may be due to an effusion, pain, or extension contracture.

Figure 3-5 Full extension of the knee is the zero or neutral point.

(From Tria AJ Jr, Klein KS: An illustrated guide to the knee, New York, 1992, Churchill Livingstone.)

Palpation

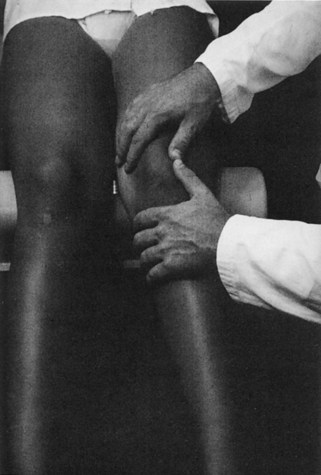

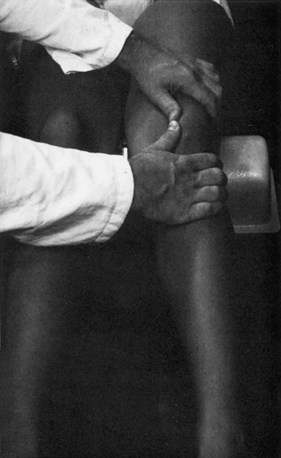

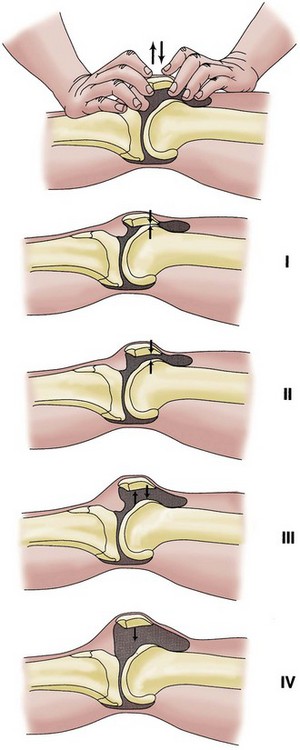

Effusions can be graded in size by compressing the suprapatellar pouch and then noting any fluid (grade 1), slight lift-off of the patella (grade 2), a ballotable patella (grade 3), or a tense effusion with no ability to compress the patella against the femoral sulcus (grade 4) (Fig. 3-6).

Figure 3-6 Effusions of the knee are graded from 1 to 4.

(From Tria AJ Jr, Klein KS: An illustrated guide to the knee, New York, 1992, Churchill Livingstone.)

The Patellofemoral Joint

Examination of the patellofemoral joint includes both static and dynamic evaluation. Visual inspection should be performed to note any evidence of quadriceps atrophy or vastus medialis obliquus hypoplasia. Prepatellar swelling or erythema may be present, suggesting prepatellar bursitis. The Q angle should be measured with the patient supine and the hip and knee in full extension. If the knee is allowed to flex slightly, the Q angle will decrease with internal rotation of the tibia on the femur (Fig. 3-7). The average male Q angle is 14 ± 3 degrees, and the average female Q angle is 17 ± 3 degrees.1 A Q angle greater than 20 degrees must be noted as excessive. Tracking of the patella from full extension into flexion should be recorded visually. In full extension, the patella begins with contact of the median ridge and the lateral facet with the lateral side of the sulcus. The patella moves more centrally and the facets increase their contact with the femoral condyles as flexion increases (Fig. 3-8). Excessive lateralization of the patella with full extensions will result in a pathologic “J-sign.” This may be seen in patients with recurrent lateral subluxations or excessive ligamentous laxity, or following a traumatic lateral patellar dislocation.

Figure 3-8 Flexion of the knee decreases the Q angle as the result of internal tibial rotation.

(From Tria AJ Jr, Klein KS: An illustrated guide to the knee, New York, 1992, Churchill Livingstone.)

Because the patellar facets do not begin to contact the femoral sulcus until the knee is flexed 30 degrees, the medial and lateral patellofemoral articulation should be palpated at this degree of flexion. This can be accomplished by allowing the leg to bend slightly over the edge of the table or by placing a small pillow below the knee. Direct patellar compression is performed and may elicit pain over the medial or lateral facet, depending on the location of the pathology (Fig. 3-9). Direct compression can be performed at progressively increasing degrees of flexion to further isolate the location of a chondral lesion. The patellar grind test consists of quadriceps contraction while direct compression is placed on the patella. When performed in full extension, entrapped synovium can cause pain even with a normal patellofemoral joint. This is especially true in the patient with patella alta. This is an unreliable test and is not recommended. The examiner should complete the static aspect of the examination by evaluating for the presence of tenderness over the medial and lateral facets of the patella, the medial and lateral retinacula, the insertion of the quadriceps tendon, and the insertion of the patellar tendon.

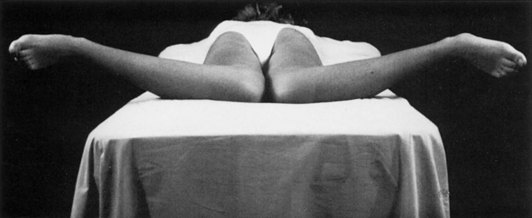

Dynamic evaluation should include observation of patellar tracking with active knee flexion and extension. This is performed with the patient seated on the edge of the examination table and the knees bent over the side (Fig. 3-10). The patella can be seen engaging the trochlea at 10 to 30 degrees of flexion.2 Any excessive lateral displacement with full extension or any maltracking should be noted. After patellar tracking is assessed, the examiner should place one hand over the anterior aspect of the patella and provide resistance to knee extension with the opposite hand. Knee extension against resistance will elicit any patellofemoral crepitus or pain from chondral pathology. The half-squat test is a different technique to load the patellofemoral joint in a similar manner. With this test, the patient is asked to hold the position of a half-squat and report the presence of anterior knee pain.

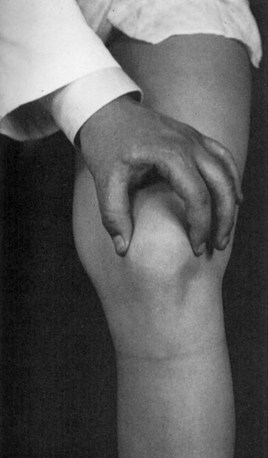

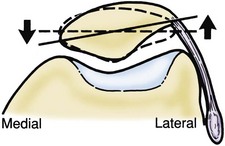

Patellar tilt, mobility, and the presence of patellar apprehension are then evaluated. The patient is placed in a supine position. In full extension, neutral or slight lateral tilt of the patella is normal. The inability to tilt the patella past neutral indicates an excessively tight lateral retinaculum (Fig. 3-11). With the knee flexed 20 to 30 degrees, patellar mobility is assessed. Both medial and lateral translation should be noted. Translation should not exceed two quadrants in either direction.3 If less than one quadrant of medial translation is present, this suggests an excessively tight lateral retinaculum. Patellar apprehension should also be assessed with the knee flexed 20 to 30 degrees (Fig. 3-12).4 Medial apprehension may be seen but is much less frequent and often iatrogenic in nature following an excessive lateral release. Lateral apprehension is more common and may suggest recurrent subluxations, traumatic lateral patellar dislocation, or excessive ligamentous laxity.

Examination of the patellofemoral joint is not complete until the hip is examined. Passive and active range of motion of the hip should be recorded. Excessive internal rotation of the hip secondary to increased femoral anteversion will result in an increased Q angle and may be part of a “miserable malalignment” type syndrome.5 Hip rotation and femoral anteversion should be assessed with the patient in a prone position (Fig. 3-13). Internal rotation that exceeds external rotation by greater than 30 degrees is considered pathologic and should be noted.6 Limited range of motion or pain with hip range of motion may signify hip pathology as a source of referred pain. This suggests that further evaluation of the hip should be performed before an accurate diagnosis can be made.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree