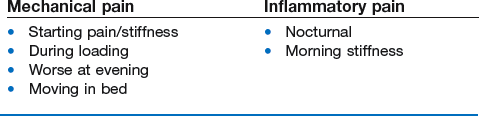

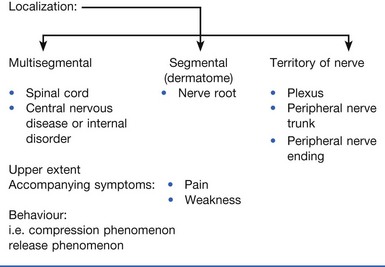

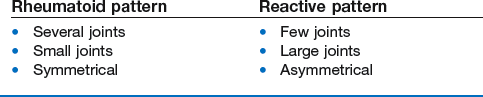

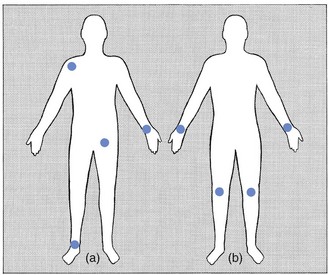

4 First of all, not every detected anatomical lesion causes pain or dysfunction. Asymptomatic lesions do exist and are present in numbers that are much larger than previously assumed: asymptomatic herniations in cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine are present in up to 50% of the population.1,2,3 Also the high prevalence of rotator cuff tears in elderly asymptomatic individuals is very well known.4,5 It is estimated that in the general population, approximately two-thirds of all rotator cuff tears are asymptomatic.6,7 Large numbers of asymptomatic lesions have also been demonstrated in the knee. A recent MRI study on asymptomatic soccer players demonstrated one or more MRI abnormalities in no less than 64%. Another study with MRI scans performed on the knees of asymptomatic male professional basketball players demonstrated an overall prevalence of articular cartilage lesions of 47.5%8 and meniscal lesions of 20%.9 • Some regions in the body are always tender to touch (e.g. lesser tuberosity at the shoulder, lateral epicondyle at the elbow, border of the trapezius muscle). • Some structures lie too deeply and cannot be reached by the palpating finger (e.g. capsule of the hip joint, cruciate ligaments at the knee). • The painful area does not always correspond to the site of the lesion (referred pain) and referred dural tenderness is sometimes present. • Some patients with altered perception or desire to deceive the examiner may produce misleading responses. This approach has some advantages: • The structures that participate in the movement are well known (applied anatomy). • The movements are easily controllable and reproducible. Pain may be provoked, but also limitation can be seen and weakness is not difficult to detect. The inter- and intra-tester reliability is quite high.10–15 • Patterns can be found: pain patterns, patterns of limitation and patterns of weakness. The recognition of a known pattern confirms the symptoms and signs presented.16 This distinction is one of the pillars on which the whole system of orthopaedic medicine rests. The soft tissues of the locomotor system can be divided on the one hand into tissues that can contract (the contractile structures) and on the other hand, tissues that do not possess this capacity (the non-contractile or inert structures) (Box 4.1). The complex of muscle origin, muscle belly, musculotendinous junction, body of tendon, tenoperiosteal junction and also the bone adjacent to the attachment of the tendon are considered clinically as contractile (Fig. 4.1). Orthopaedic medical disorders produce symptoms and signs that may be difficult to analyse objectively. Patients who have a reason to assume disorders for some type of personal gain, therefore, commonly use clinical features in the locomotor system to try to establish their credibility (see online chapter Psychogenic pain). Cyriax said: ‘Every patient contains a truth. He will proffer the data on which diagnosis rests. The doctor must adopt a conscious humility, not towards the patient, but towards the truth concealed within the patient, if his interpretations are regularly to prove correct’.17 The symptoms may be present without interruption from their onset. However, it is also possible that the patient describes a recurrence (see Box 4.2). A very important distinction should be made between the following definitions. Referred pain is a very typical feature in non-osseus lesions of the locomotor system. It is mostly segmental and thus experienced in a single dermatome, which indicates the segment in which the lesion should be sought. Reference of pain is influenced by the severity of the lesion: the more severe it becomes, so giving rise to a stronger stimulus, the further distally does the pain (usually) spread. The reverse also holds: reduction in the distal distribution is synonymous with improvement.18,19 Pain coming on in one place as it leaves another indicates a shifting lesion. The same happens in soft tissue lesions. A good example is central backache, which becomes unilateral, then later on shifts to the buttock and finally to the lower limb – the backache has become sciatica. This shift can only be explained as follows: a structure lying in the midline and originally compressing the dura mater (backache) has shifted to one side and now compresses the dural sleeve of the nerve root (root pain). To be able to shift, that structure has to lie in a cavity and, because the pain was originally central, this has to be a central cavity. The only structure lying in a central cavity and able to change its position is the intervertebral disc: there is no other possibility (Fig. 4.2). There are many different ways of describing pain: it is amazing how much variation patients can achieve in their vocabulary and how many different descriptive terms can be used for the different sensations perceived. The reason lies in the fact that pain is mainly an unpleasant emotional state that is aroused by unusual patterns of activity in specific nociceptive afferent systems. The evocation of this emotional disturbance is contingent upon projection to the frontal cortex.20,21 The nature of the pain may have some diagnostic value: everybody knows the throbbing pain of migraine, the stabbing pain of lumbago or the burning sensation of neuralgic conditions. Although the way the patient describes the pain may sometimes point to a certain disorder, it can also indicate the emotional involvement of the patient with the lesion. Pain may have either a mechanical or an inflammatory character (Box 4.4). Mechanical pain (e.g. in arthrosis) is characterized by pain and stiffness at the beginning of a movement; augmentation when load is put on the joint; pain at the end of the day and absence of pain at rest, although moving in bed may also be uncomfortable. Inflammatory pain (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, gout or infectious arthritis) wakes the patient at night and gives rise to frank stiffness early in the day.22 A momentary subluxation of a loose fragment of cartilage in a joint This happens quite often in the lumbar spine, the knee and the hip and less frequently in the elbow, ankle and subtalar joints. If there are any signs found during clinical examination, they will be articular – a non-capsular pattern (see p. 74). The combination of twinges and articular signs is pathognomonic of the existence of internal derangement. Non-painful sensory disturbances, paraesthesia, are strongly indicative of a condition that originates in a nerve (Box 4.5). They may result from an intrinsic lesion (primary neuritis or secondary polyneuropathy) or from an extrinsic cause (compression). They may also vary in quality and in intensity. In orthopaedic medicine the variation lies between numbness and real pins and needles. It is very often described as ‘tingling’. In entrapment neuropathies, knowledge of what brings the pins and needles on will show whether a compression phenomenon or the release phenomenon is acting (see pp. 26–27). For example, pressure on a small distal nerve gives rise to paraesthesia and analgesia in the cutaneous area of that nerve during the time of compression (e.g. meralgia paraesthetica). However, when a nerve trunk or nerve plexus becomes compressed, the paraesthesia are felt in a larger area, corresponding with the territory of that nerve and occur only after the compression has ceased (e.g. thoracic outlet syndrome). Nerve root compression results in segmental pain and paraesthesia felt within the corresponding dermatome (e.g. sciatica). Multisegmental bilateral paraesthesia indicates a lesion in the spinal cord. When limitation of movement is mentioned, its nature will have to be determined during the functional examination: limitation of active movements only, or limitation of both active and passive movements, and in this case whether it is of the capsular or of the non-capsular type. End-feel at the end of the passive movements and the relationship between pain and end-feel must also be ascertained (see pp. 73–74). Other questions, if appropriate, are asked about similar symptoms, past or present, in other parts of the body, especially other joints (see Box 4.6). If the answer is positive, conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, spondylitic arthritis, Reiter’s disease and gout should be suspected and further examination is required. Disorders of rheumatoid type (rheumatoid arthritis, lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, dermatomyositis) are characterized by the symmetrical joint involvement, usually of the small joints (e.g. metacarpophalangeal joints). Arthritis of reactive type (e.g. peripheral joint involvement in ankylosing spondylitis, ulcerative colitis, Reiter’s disease, sarcoidosis or psoriatic arthritis) affects a few large joints (e.g. shoulder, hip or knee) asymmetrically (Fig. 4.3). Inquiries should also be made about previous treatments, which may give some idea of the chance of success of the proposed therapy. Previous surgery, its timing and indication are noted – it is not impossible that the present condition is the outcome of previous intervention (Box 4.7).

Clinical diagnosis of soft tissue lesions

Introduction

Principles of diagnostic procedure in orthopaedic medicine

2 Look for objective physical signs

3 Avoid palpation as much as possible

The function of the different tissues is known

4 Functional testing: the principle of ‘selective tension’

5 Use physiological movements as much as possible

Normal movements may become disturbed

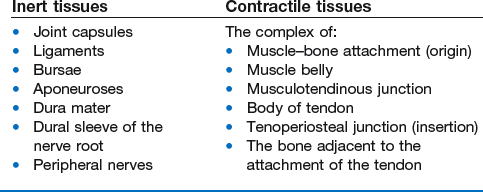

6 Distinguish between inert and contractile tissues

Soft tissues are either inert or contractile

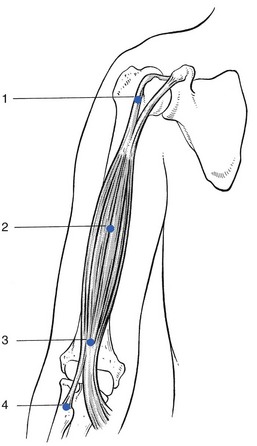

Contractile structure

10 Keep the balance between credulity and excessive scepticism

Objectivity is a fair attitude

11 Request technical investigations only when necessary

Clinical evaluation

History

Taking the history

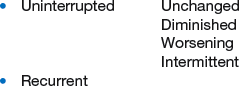

Progression/evolution

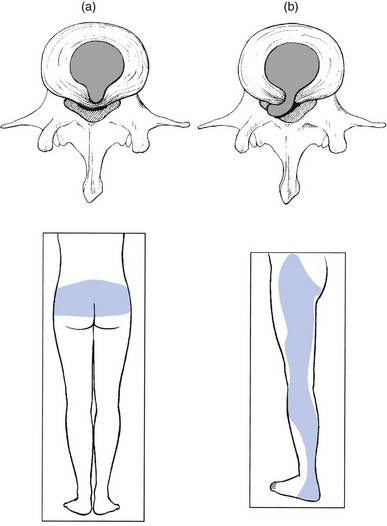

Reference of pain

Shifting pain

Actual symptoms

Pain (Box 4.3)

Paraesthesia

Functional disability

Further questions