Clinical Assessment and Patient Selection for Hip Arthroscopy

Olusanjo Adeoye

Marc R. Safran

There has been a recent increase in interest and awareness of nonarthritic hip injuries in the active population. As our understanding of hip pathology progresses, noninvasive imaging techniques improve, and arthroscopic and other minimally invasive operative techniques continue to evolve, the focus is shifting toward earlier identification and treatment of hip pathology. Emerging treatment options may address some of these conditions in the early stages and prevent or slow the progression of hip degeneration.

The differential diagnosis of hip pain is quite broad in the active population. Hip pain can be caused by intraarticular or surrounding extra-articular pathology or be referred to the hip from a variety of truncal sources. Intraarticular sources of hip pain include labral tears, chondral damage, ligamentum teres tears, loose bodies, femoroacetabular impingement, hip dysplasia, and hip instability (15). Periarticular sources include greater trochanteric bursitis, snapping hip syndrome, hip flexor strains and tendinopathy, hamstring strain and tendinopathy, piriformis syndrome, and gluteus medius tendinopathy and tears. Furthermore, the hip is commonly a location of referred pain from the lumbar spine and sacrum as well as the abdomen and pelvis. It is important to examine the spine, pelvis, and abdomen to rule out referred pain from those areas. Details of those examinations are beyond the scope of this chapter.

Making a correct diagnosis is imperative to appropriate management of hip injuries. A careful history, physical examination, and standard radiographs may provide important clues, with advanced imaging, such as MRI arthrography, helping confirm the diagnosis. Arthroscopy has also been advocated as a diagnostic tool for intraarticular hip pathology, although this is necessary in only a small minority of patients. As we begin to understand hip anatomy, mechanics, and pathomechanics better, improvements and refinements in examination and imaging will also advance, along with management options.

CLINICAL EVALUATION

Pertinent History

The first step in evaluating the hip is to obtain a thorough history from the patient. The presence or absence of trauma (including mechanism of injury), as well as the location of the pain, onset, duration, and severity of symptoms should be determined. Exacerbating and alleviating factors along with specific limited activities of daily living should be identified. The examiner should inquire about prior hip consultations, past surgeries, old injuries, and prior treatments including activity modifications, oral medications, physical therapy, injections, and assistive devices. Recreational history and athletic participation should also be probed. It is important to discern a history of ligamentous laxity or treatment for acetabular dysplasia as an infant. It is also important to obtain a history of hip pain as an adolescent that may be a clue to previous hip problems such as slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) and Legg-Calve-Perthes (15).

A thorough history will help delineate intra-articular versus extra-articular sources of pain. Patients with symptomatic intra-articular problems, such as chondral flaps and labral tears, will often complain of pain and mechanical symptoms (17). Typically, the pain is deep and localized in the anterior groin or inguinal region, although this pain may be referred to the medial thigh, the region proximal to the greater trochanter laterally, or in the buttocks. Frequently, patients will note the pain is deep within the joint, grabbing their hip with the thumb in the inguinal region and the long finger posterolaterally, stating the pain is at the junction of the fingers—known as the C-sign (Fig. 45.1) (1, 2 and 3). This can be misinterpreted as lateral soft tissue pathology; however, the patient often describes deep interior hip pain. Posterior-superior pain requires a thorough evaluation in differentiating hip and back pain.

Other characteristics of intra-articular sources of mechanical hip pain include discreet episodes of sharp pain

with weightbearing that may be exacerbated by pivoting or twisting, discomfort with sitting with the hip flexed, and pain or catching on arising from a seated position. Patients may also complain of catching, clicking, popping, or locking within the joint with ambulation or other hip motion, although this is less specific for intra-articular sources of symptoms.

with weightbearing that may be exacerbated by pivoting or twisting, discomfort with sitting with the hip flexed, and pain or catching on arising from a seated position. Patients may also complain of catching, clicking, popping, or locking within the joint with ambulation or other hip motion, although this is less specific for intra-articular sources of symptoms.

FIGURE 45.1. Depicting the “C-sign,” a characteristic sign, patients with intra-articular hip pain will often demonstrate. |

Patients with extra-articular sources or referred pain will have varying complaints. Pain located in the thigh or buttocks, or pain that radiates distally below the knee, is likely to originate from the lumbar spine or buttock and proximal thigh musculature. Pain located in the lower abdomen and/or at the adductor tubercle can indicate athletic pubalgia or osteitis pubis. Pain located around the greater trochanter and associated with snapping can be external snapping hip syndrome. External snapping hip is often visible, or seen by the patient and others, and sometimes is described as the hip dislocating by the patient. Internal snapping hip is usually audible or palpable and felt deep inside or in the groin. Identification of associated symptoms such as weakness or numbness, back pain, and exacerbation with coughing or sneezing, may indicate thoracolumbar pathology. Individuals with athletic pubalgia may also note pain with sit-ups. Furthermore, one must remember that hip problems may present as pain in the knee.

A general medical and surgical history, as well as any developmental problems, should be explored. Patients should specifically be asked about systemic illnesses such as malignancy, coagulopathies, and inflammatory disorders. Various coagulation and metabolic disorders such as abnormality of lipids, thyroid, homocysteine, and clotting mechanisms have been shown to impede vascular supply to the femoral head. Social history should be reviewed to determine current or prior use of alcohol, steroids, and tobacco, or altitude issues, which might place the patient at risk for osteonecrosis.

The report of present illness, surgical and medical history, and family history should provide the clinician with enough information to develop a preliminary differential diagnosis. This differential diagnosis will allow the clinician to pay special attention to specific areas of the complete hip examination.

Physical Examination

Physical examination of the hip follows the same basic principles of any other area of the body. However, the hip is difficult to examine due to it being a deep structure, surrounded by a thick envelope of muscles and other soft tissues, that is also well constrained. Furthermore, examination of the hip is difficult because hip pain may be a result of intra-articular hip pathology as well as a myriad of extra-articular and referred sources of pain. It is crucial to perform a consistent, comprehensive physical examination to best identify the underlying diagnosis. A systematic approach includes inspection, palpation, range of motion, strength, and special or provocative tests (4, 16, 17). A complete examination of the hip must be performed, even if the differential diagnosis appears very narrow, to help reduce the likelihood of an incorrect diagnosis. The order of the examination should be easy on the patient and flow for the physician. An efficient order of patient positioning for the examination begins with standing tests followed by seated, supine, lateral, and ending with prone tests (2).

Inspection

Observe the patient as they walk into the room, how they are sitting, how they get up from the interview chair, and how they transfer to the examination table—these may be essential initial clues in the examination of the hip. Notation is made with regard to favoring, splinting, or compensating for the injured limb. Patients with piriformis syndrome may lean off the affected hip, whereas some patients with femoroacetabular impingement or anterior labral tear may slouch in the chair to reduce hip flexion. Antalgic gait, with decreased stance phase, shortened swing phase, or avoidance of hip extension is noted. Also, Trendelenburg gait may be seen because of abductor weakness or as the patient tries to place their center of gravity over the hip, reducing the forces on the joint. Abductor weakness is present if the pelvis drops contralateral to the stance leg or the patient shifts his/her entire body over the stance leg to compensate for the deficient abductors. As this weakness progresses, a compensatory shift of weight toward the affected side may occur. Known as an abductor lurch, this gait pattern places the center of gravity closer to the hip and thus decreases the force required from the abductors.

Observation for swelling and bruising at the greater trochanter for bursitis or at the iliac crest for hip pointers or avulsion fractures, for example, may also provide a clue to the diagnosis. Observation of the pelvic region and spine for asymmetry, deformity, masses, redness, atrophy, malalignment, and pelvic obliquity is also made. Leg lengths are measured standing (assessing from the back for pelvic tilt) and laying supine (measured from the anterosuperior iliac spine [ASIS] to the medial malleolus bilaterally).

Palpation

Intra-articular pathologies usually do not have palpable areas of tenderness, although compensation for longstanding intra-articular problems may result in tenderness of muscles or bursae. Palpating bony prominences around the hip is an essential part of the physical examination and is very useful in delineating extra-articular causes of pain. Common areas of tenderness include the greater trochanter with trochanteric bursitis and snapping hip from the iliotibial band (Fig. 45.2). Tenderness posterior to the greater trochanter is suggestive of piriformis tendonitis, whereas tenderness just superior to the greater trochanter may be because of gluteus medius tendonitis. The ASIS is the origin of the sartorius, a common location of apophyseal avulsion fractures in adolescent athletes. Just medial to the ASIS, the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve crosses under the inguinal ligament. Compression of the nerve at this site, known as meralgia paresthetica, may produce dysesthesias over the proximal anterolateral aspect of the thigh. Reproduction of symptoms with deep palpation just medial to the ASIS is diagnostic for this condition. Tenderness and swelling at the iliac crest following direct trauma is commonly known as a “hip pointer” or in the skeletally immature athlete may be related to iliac crest avulsion injury. The anterior inferior iliac spine (AIIS) is the origin of the rectus femoris. Tenderness at this location in a skeletally immature athlete suggests an apophyseal avulsion injury.

Tenderness at the pubic symphysis or ramus may occur as the result of recurrent stress created by powerful adductors. This condition, termed pubic symphysitis or osteitis pubis, is most frequently seen in soccer and hockey players. The ischial tuberosity may be palpated with the patient either in the prone or in the supine position with the hip flexed. Acute tenderness at this site is found in hamstring avulsion injuries, but tenderness may also be seen with hamstring tendinopathy. Tenderness in the absence of acute injury may be attributable to inflammation of the overlying bursa. Ischiogluteal bursitis, or weaver’s bottom, is most commonly found in seated athletes such as rowers, bikers, and equestrian athletes.

Other areas of pain, as located by the patient, should be palpated. It is important not to forget to palpate other potential areas of referred pain to the hip, including the lumbar spine, sacrum, and sacroiliac (SI) joint. Palpation of the femoral artery should be included in the general hip examination as well as the neurovascular evaluation because an aneurysm of this artery may uncommonly cause swelling and pain about the hip.

Range of Motion

Range of motion is assessed checking the normal, unaffected limb first (Table 45.1). It is important to evaluate hip range of motion with the patient in the seated, supine, and prone positions. Excessive femoral anteversion will present with increased internal rotation and decreased external rotation. It is important to distinguish motion from the hip joint itself from compensatory motion occurring in the pelvis and lumbar spine. Flexion contracture is measured with the contralateral hip flexed and the lumbar spine stabilized with the examination table using the Thomas test (Fig. 45.3). This is performed properly by having the subject flex hip to the chest. If there is no

flexion contracture, the hip being tested remains on the examining table. If a flexion contracture is present, the patient’s contralateral leg will rise off the table.

flexion contracture, the hip being tested remains on the examining table. If a flexion contracture is present, the patient’s contralateral leg will rise off the table.

Table 45.1 Active normal range of motions of the hip | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

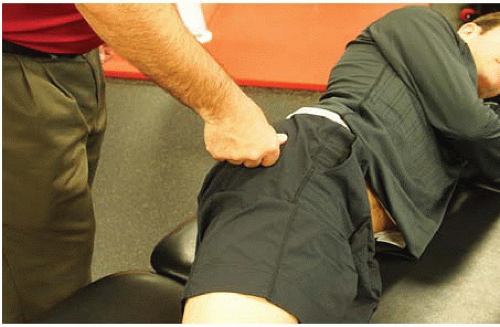

FIGURE 45.3. Thomas test. Utilized to evaluate for hip flexion contractures. If there is no flexion contracture, the extended hip and extremity will be flat on the examination table. |

Hamstring tightness is also evaluated by measuring the popliteal angle. With the subject supine, the hip is flexed 90° with the knee flexed. The knee is then passively extended. The degree of knee extension is indicative of hamstring tightness, with full extension indicative of hamstring flexibility.

Hip abductor tightness or tensor fascia lata contracture is measured using the Ober test (Fig. 45.4) (2, 4, 5). In the lateral decubitus position, the lower hip and knee is flexed for stability. The examiner then passively flexes the hip being examined to 90° and then abducts the hip fully and extends the hip past neutral with the knee in 90° of flexion. At this point, the hip and knee are allowed to adduct while the hip is held in neutral rotation. If the knee does not reach to midline, then the hip abductors are tight.

Rectus femoris tightness can be assessed in the prone position. The patient’s knee is passively flexed. If on flexion of the knee the ipsilateral hip also flexes, then the rectus femoris is tight and the test is positive. This test is also known as Ely’s test (2, 4, 5). The degree of knee flexion should also be compared between the two sides to assess for rectus femoris tightness (Fig. 45.5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree