Clinical Approach to The Patellofemoral Joint

John P. Fulkerson

CLINICAL EVALUATION

Diagnosis of the patellofemoral joint has been challenging for orthopedic surgeons and other musculoskeletal clinicians. Because diagnosis around the anterior knee can be complicated, the prudent clinician will allow the time necessary to acquire a full history of the problem and also time for a thorough clinical evaluation. Designing proper treatment is only possible with a thorough understanding of each patient’s problem.

History

Of paramount importance with regard to diagnosis in patients with anterior knee, pain is establishing the nature of the problem. Has the patient experienced instability? Has the patient had predominantly pain or instability and pain? Confusing this issue, at times, is the fact that instability or imbalance of forces around the anterior knee can also lead to pain. It is the clinician’s responsibility to discern the differences here and determine what is going on.

Listening to the patient has proven very important. William Post (1) published an article regarding the importance of pain diagrams, he established through asking patients to fill in a picture of the knee, specifically identifying location of pain, that patients will generally point the clinician in the right direction. By the same token, if pain is not the primary consideration, then patient may not be able to complete the pain diagram and therefore the clinician must help the patient to better address the nature of his/her problem, usually instability. So, a careful series of questions for the patient regarding the nature of his/her problem will be most helpful. In particular, the clinician should ask the location of pain, timing of pain (is it activity related?), and initial onset (was there an injury?). Any pattern of referral above or below the knee is important. One should recall also that a problem in the hip can cause pain radiating down to anterior thigh and sometimes to the region immediately above or around the patella. I have found that approaching diagnosis of the anterior knee with a few provocative questions often leads to important insights. For instance, trying to define the nature of the pain (sharp, dull, tingley, localized, diffuse, etc.) will provide some clues.

If the patient has instability, one must determine causes of instability events and whether the problem is really instability of the patella or giving away of the knee related to weak quadriceps, a meniscus tear, ligament deficiency, or some other dysfunction of the knee.

In the patient who has had previous surgery, one should be aware of the possibility of medial patella instability after lateral release or realignment of the anterior knee. Patients with medial patella instability will often give a history of very sudden collapse of the knee. The nature of these episodes is slippage of the patella from too far medial back laterally into the trochea, very suddenly. This can be misleading, as such patients experience their patella going laterally when in fact it is indeed going laterally but from too far medial. Failing to recognize this may cause the clinician to believe that the patient still has lateral patella instability and potentially lead to additional surgery aimed at moving the patella further medially. The only way to make this differentiation is to understand the problem and the nature of the episodes. A proper history aimed at differentiating these problems is of paramount importance. So regarding history, most important is listening to the patient. It is surprising how many times the patient will lead the clinician to accurate diagnosis simply by having a chance to express details of the problem, prompted by targeted questions. I had an overweight patient in my office yesterday who had twisted his knee 2 years ago. He had had extensive (and expensive) physical therapy and was miserable with pain. No one had put a finger on his tender semimembranosus tendon. After injecting it, his pain vanished for the first time in 2 years.

Physical Examination

Optimal physical examination with regard to the anterior knee should involve examination of the patient supine, prone, standing, and moving.

First, notice patient’s affect and body habitus. Particularly in adolescents and young adults, excessive attachment to the parent or domination by a parent may pertain as well.

With the patient supine, evaluate flexion and extension in the knee to see if there is any visible sign of lateral patella tracking. The J sign in particular will become evident at this time. In patients with patellofemoral, pain or ongoing pain is not uncommon for the apparent mechanical function of the patellofemoral joint to seem normal. On the contrary, many patients with an instability problem will manifest some evidence of lateral patella tracking or patella tilt. Of course, there are patients who complain of pain who have evidence of malalignment (a net imbalance of the patellofemoral joint, usually caused by multiple structural factors, leading to suboptimal or inappropriate load distribution in the patellofemoral articulation) and patients without any evidence of malalignment who have recurrent instability episodes. All of this will pertain to the nature of the specific deficiency or imbalance.

Next, the examiner should palpate the entire anterior knee methodically and precisely oriented to anatomic detail. Particularly in patients with a complaint of anterior knee pain, the examiner should search for tender spots and should again ask the patient to identify any specific source of pain. Together, the examiner and the patient may be able to “zero in” on a source of pain. It is surprising how often a patient will point directly to a source of pain in the peripatellar retinaculum that has been missed, sometimes for years. So, peripatellar examination is extremely important, particularly as small nerve injury, presumably related to aberrant retinacular stress, is common in the retinaculum of patellofemoral pain patients (2, 3). Palpate everything including the vastus lateralis tendon, lateral retinaculum, the patella tendon, the retro patella tendon region, the medial retinaculum particularly vastus medialis obliques (VMO) tendon insertion, and the quadriceps tendon itself. Any of these areas can be a source of anterior knee pain. If the patient has had previous surgery, be sure to palpate every portal and incision to identify if there might be a neuroma or tender scar causing pain. If a primary source of pain can be identified, this area should be prepped and injected with a local anesthetic to see if the pain disappears upon specific injection. If this is successful, adding corticosteroid to the injected site maybe warranted, and ultimately, resection of the painful tissue may be curative (4).

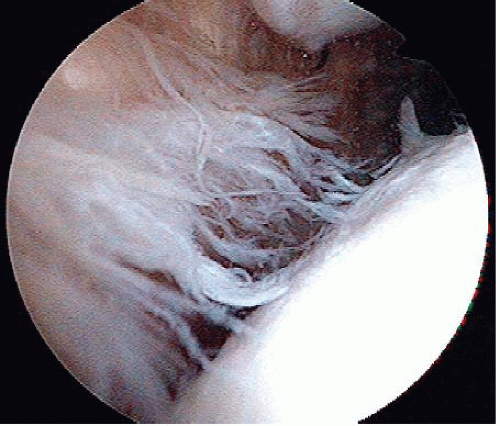

Once the retinacular examination is finished, the clinician should use palpation also to help with intra-articular diagnosis. Particularly, the medial infrapatella space should be palpated upon flexion and extension of the knee, looking for evidence of a pathologic plica (Fig. 59.1). Typically, patients who have a symptomatic plica will identify the nature of pain with this area palpated partially if there is a click associated with palpation.

Some examiners like to palpate the lateral facet of the patella by displacing the patella laterally and palpating. I have found this particular method to be confusing as the retinaculum is also stretched quite tensely with this technique. It is important to differentiate the nature of any pain noted on palpation.

Following this, patient should be displaced supine with the knee extended, pushing the patella medially, and then the knee is flexed suddenly. Contrarily, the patella should be displaced laterally and the knee flex abruptly. Using this particular method, the examiner would identify if there is a problem with relocation pain or instability such as is experienced in patient with medial patella subluxation (5). Such patients have a patella that “wanders” to far in one direction or the other and relocates suddenly. This is particularly striking in the patient with medial patella instability. In such patients, the patella sits slightly medial then immediately relocates very abruptly upon flexion of the knee, sometimes on stairs and unexpectedly causing the patient to fall to the ground as the patella relocates from too far medial back into the central trochlea with sharp intense pain and giving away. I have found this method to be helpful in differentiating medial from lateral patella instability.

To examine for integrity of the medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL), the patella is pushed laterally while palpating medially, and then the knee is slowly flexed to see if the MPFL is pulling the patella into the central trochlea. Normally, this occurs promptly and completely by 30° of knee flexion. If the patella stays lateral, the MPFL is deficient. One must be careful not to dislocate the patella (Fig. 59.2).

Following this, the patella should be compressed against the trochlea while the knee is flexed and extended looking for crepitus or pain. Using this method, the examiner can determine to what extent the pain may be elicited from articular compression, and the location of the painful articular lesion may be determined as well. In a distal pole patella articular lesion, the pain will be elicited in early flexion, whereas in a crush, proximal pole patella lesion, crepitus, and pain will more typically be found upon compression of the patella with the knee flexed 70° to 110°. This differentiation becomes very important in surgical planning. One must determine how best to unload a specific, painful lesion on the patella.

Some sense of laxity around the anterior knee should also be acquired looking at “quadrant laxity.” Essentially one is testing overall ligament laxity, and this, together with an appraisal of general joint laxity of the elbow thumb and fingers will help in determining quality of the patient’s connective tissue.

Patient’s hamstring flexibility should be examined and then place the patient prone to evaluate rotation of the hips and quadriceps tightness. With the knee extended in the prone position, one can also palpate the peripatellar retinacular tissue as the extensor mechanism relaxes well in this position.

The patient is then asked to walk while the examiner evaluates gait to see if there is evidence of antalgia pertaining to the hip or knee. A single leg knee bend is important both to establish quadriceps support but most importantly to evaluate core stability at the hip level as well as pronation at the foot and ankle. It is surprising how many patients will show evidence of inadequate support of the lower extremity with excessive internal rotation at the hip. Be sure to establish the level of lower extremity support in any patient with patellofemoral instability or pain such that physical therapy may be guided appropriately to improve over all lower extremity function and balanced tracking of the patella during activity.

I like to have the patient do a “step down” test in which the patient stands on a small step and steps down on one side and then the other, looking specifically for evidence of pain, the patient who experiences intense pain upon early step down may well have a distal patella articular lesion as a source of pain. This distal pole articular lesion will often be missed if this test is not done. In the patient with reproduction of pain upon doing this test, unloading the distal pole of the patella may be necessary by anterior or anteromedial tibial tubercle transfer at some point if other measures fail including a full program of core stability. Further evaluating core stability, the patient should jump down from a step while the examiner watches to see if there is excessive internal rotation at the hip level producing functional valgus at the knee and pronation at the foot and ankle level. Core stability training may be what is needed in such patients.

Imaging

In most patients with anterior knee pain or instability, I recommend four radiographic views, taken with precision, in the office. In addition to standard AP views, I like to take a 30° knee flexion weight-bearing PA radiograph of the knee. Third is the precise lateral, posterior condyles overlapped. Finally is the axial view. My preference is the 30° knee flexion Merchant axial view.

The lateral (6) and Merchant axial (7) are most important in the patient with anterior knee pain and instability. Without fluoroscopy, it is difficult to obtain a true lateral radiograph but our technicians developed a technique of palpating the posterior condyles while the patient stands next to the X-ray cassette. This technique has been surprisingly accurate in determining when the knee is truly lateral such as the posterior condyle will overlap on the radiograph. Although every picture will not be perfect, we have found that for screening purposes in the office, this has worked out quite well. Evaluating the lateral requires some experience. One must learn to identify the medial and lateral trochlear condyles in the central trochlea as seen on lateral radiograph. One must also learn to identify the appearance of a patella that is tilted, subluxated, and or subluxated versus normal on the lateral view.

Good office radiographs are all that is needed in the majority of patients. Ninety degrees knee flexion axial views are of very limited value in my experience. In order to obtain a good axial view, one will need either bolsters cut to the appropriate angle or a Merchant frame that will place the knee in a desired amount of flexion.

One can readily see evidence of subluxation and/or tilt on a standard radiograph. Ronald Grelsamer (8) has made the point that a simple visual impression is most helpful as well as understanding how to interpret the lateral radiograph. For most orthopedic surgeons, it will be apparent when the patella is grossly tilted or laterally displaced in the trochlea.

The precise lateral (9) is really a better index of patella displacement, particularly tilt, as the lateral edge of the patella and the center ridge of the patella will overlap, producing a single line when the patella is clinically tilted. This is a good objective parameter. Also, on the lateral radiograph, one can appreciate the depth and structures of the trochlea.

Displacing the patella laterally, one might also consider the axial linear displacement view advocated by Urch et al. (10) In this case, a Merchant axial view is taken with the patella displaced laterally, documenting displaceability of the patella as an index of propensity for dislocation.

Tomographic Imaging

MRI can be helpful in a detailed analysis of patella alignment; however, these studies are often not necessary in my experience. Good office radiographs, put together with accurate clinical, physical examination are all that is necessary in most patellofemoral patients. In more difficulty cases, and in cases when one wants to rule out other intra-articular pathology, MRI may be helpful. Essentially, I recommend obtaining MRI only very selectively. It has been useful for determining the medial-lateral distance between the tibial tubercle and the central trochlear groove (commonly known as the TT-TG index). Too often MRI is used instead of proper physical examination and when radiographs have not been done properly or evaluated thoroughly. Tomographic images with progressive knee flexion has been possible in some centers, even weight-bearing, but this is expensive and generally not available.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree