Clavicle Fractures: Open Reduction and Internal Fixation

Donald A. Wiss

INTRODUCTION

Clavicle fractures are common injuries and account for approximately 35% to 40% of fractures in the shoulder region. Most occur in the midshaft, and the majority are treated nonoperatively. Nonsurgical management of this injury was based on historic, retrospective, surgeon, or radiographic studies that equated union with success. These early studies concluded that the residual shoulder deformity was primarily cosmetic and that shoulder and upper limb function were satisfactory. In the past 15 years, there has been a paradigm shift in the evaluation and treatment of clavicle fractures because contemporary studies have reported that nonoperative treatment of widely displaced fractures in adults is associated with persistent anatomical deformity, residual shoulder pain and weakness, and subtle neurologic impairment. Furthermore, recent randomized clinical trials comparing nonoperative with surgical treatment of widely displaced clavicle fractures in adults have shown a 15% rate of nonunion and symptomatic malunion, respectively, in nonoperatively treated patients. These newer studies also used patient-oriented limb-specific outcome measures such as the Constant, Dash, or ASES scores and demonstrated statistically significant improvement in validated patient outcome measures following internal fixation. These studies lend support for the use of internal fixation in selected patients with widely displaced clavicle fractures in adults to decrease the incidence of nonunion and malunion. Surgery has proven to be safe and effective with the most common complication being prominent hardware necessitating removal.

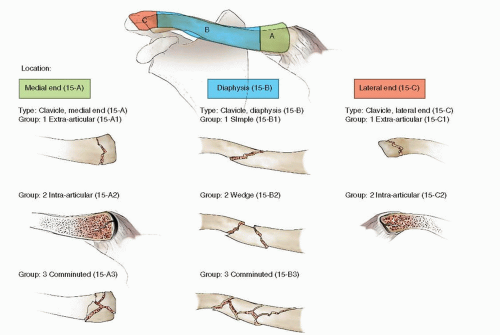

Most classification schemes for clavicle fractures divide them into three basic categories. Group I are middle third fractures, Group II are lateral third fractures, and Group III are medial fractures. Neer et al. further subdivided Group II fractures into three distinct subgroups based on associated soft-tissue and ligamentous injuries. In type I injuries, the coracoclavicular ligaments remain intact; in type II injuries, this ligamentous complex is disrupted allowing superior displacement of the lateral fragment; and type III injuries that involve the articular

surface of the acromial-clavicular joint. Several epidemiological studies show that approximately 80% of all clavicle fractures occur in the middle one-third, 15% in the lateral third, and only 5% occur medially. The AO/OTA classification of clavicle fractures is seen in Figure 1.1.

surface of the acromial-clavicular joint. Several epidemiological studies show that approximately 80% of all clavicle fractures occur in the middle one-third, 15% in the lateral third, and only 5% occur medially. The AO/OTA classification of clavicle fractures is seen in Figure 1.1.

ANATOMY

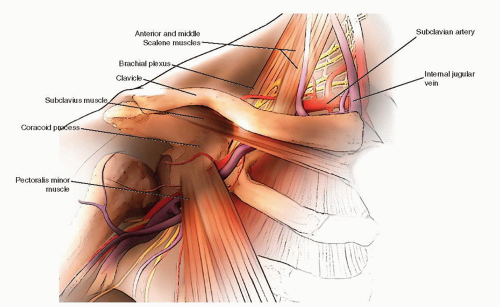

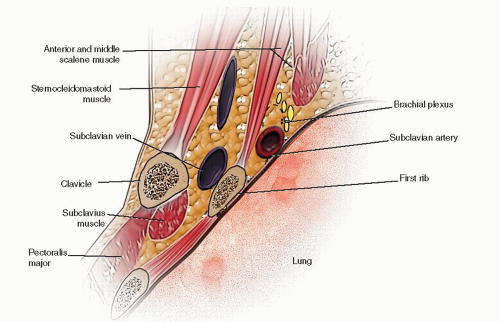

A thorough knowledge of the osseous, soft-tissue, and neurovascular anatomy of the shoulder is important if surgery is planned. The clavicle is an S-shaped bone and has an anterior convex to concave curvature when viewed from medial to lateral. The lateral end of the clavicle flattens while the medial end remains cylindrical. The midportion is densely cortical with a short and narrow medullary canal particularly in young adults (Fig. 1.2). Laterally, the clavicle is anchored to the scapula by the relatively weak acromioclavicular ligaments and the more robust coracoclavicular ligaments (conoid and trapezoid). Medially, the clavicle articulates with the sternum and is supported by the thick and strong sternoclavicular, costoclavicular, and interclavicular ligaments. Although the clavicle is predominately a subcutaneous structure, the deltoid muscle arises from the anterior-inferior portion of the lateral clavicle while the trapezius muscle arises posterior and superior in its midportion. Several other upper limb muscles take all or part of their origin from the clavicle including the subclavius, sternocleidomastoid, and pectoralis major (Fig. 1.3).

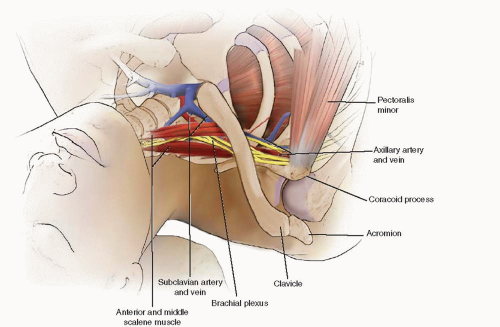

From a mechanical point of view, the clavicle functions as a strut between the shoulder girdle and the thorax, and it suspends the upper limb from the chest wall. The clavicle also provides significant protection to the subclavian vessels and the brachial plexus that lie in close proximity (Fig. 1.4).

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS FOR SURGERY

Most clavicle fractures in adults are managed nonoperatively. Nonsurgical treatment is indicated when fracture displacement is <12 to 15 mm, angulation is <10 degrees, and translation is less than a bone diameter. Treatment consists of support for the upper extremity in a sling, shoulder immobilizer, or figure-of-eight _clavicle strap to relieve pain. In adolescents, teens, and young adults, a figure-of-eight sling is simple and well tolerated. In adults, a sling or shoulder immobilizer is usually preferred. These treatment methods will not “reduce” a clavicle fracture; rather, they are intended to support the upper limb during the healing process. Within 2 to 3 weeks, most patients are able to remove their sling for simple activities of daily living, bathing, and hygiene. Serial radiographs usually show some callus by 3 weeks and substantial healing by 6 to 8 weeks. External support is discontinued when the patient has minimal pain and x-rays show progressive healing. Return to activities is dictated by local symptoms. Most patients can return to full activities by 12 weeks if the fracture is healed.

FIGURE 1.4 Cross section of the anterior chest wall showing the relationship of the subclavian vessels to the clavicle. |

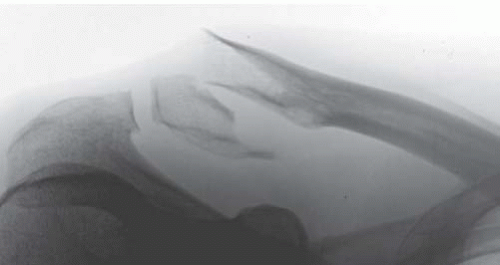

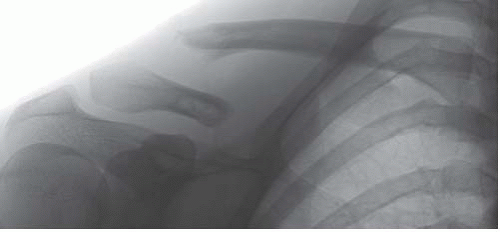

Until the turn of this century, the indications for internal fixation of clavicle fractures were very limited. Most major orthopedic textbooks supported surgery for open fractures, those with vascular compromise or progressive neurologic deficits, as well as in patients with scapulothoracic dissociation, or displaced pathologic fractures. Not surprisingly, these conditions represent a small minority of clavicle fractures seen in clinical practice. Current indications for clavicular surgery, based on recent randomized clinical trials, support the use of internal fixation in adults when there is shortening, displacement, or translation >15 to 20 mm (Fig. 1.5). Other strong indications for clavicular surgery include complex ipsilateral injuries to the scapula or proximal humerus, displaced group 2 type 2 lateral clavicle fractures, and symptomatic nonunion (Fig. 1.6).

FIGURE 1.5 X-ray of the clavicle showing a widely displaced fracture following a dirt bike accident. This is a strong indication for internal fixation. |

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

History and Physical Examination

Most clavicle fractures occur following a fall onto the upper extremity or by direct trauma to the shoulder region. Due to pain and inability to comfortably move the extremity, most patients are seen in an emergency room shortly after injury. In patients with clavicle fractures that occur following high-energy trauma such as motor vehicle, motorcycle, or a fall from a height, a full trauma workup is essential. As with all injured patients, a detailed history and thorough physical exam are necessary to accurately diagnose and treat the patient. Substantial trauma to the shoulder girdle can be associated with injuries to anatomically adjacent structures such as the head, cervical spine, chest wall, ribs, and lungs. In these patients, advanced imaging studies and consultation with other medical or surgical specialists may be required.

Most patients with clavicle fractures complain of shoulder or clavicle pain that is exacerbated by movement. Physical examination reveals swelling, tenderness along the clavicle, fracture crepitus, and deformity in displaced fractures. Ecchymosis in the supraclavicular infraclavicular or chest wall often takes 12 to 36 hours to develop (Fig. 1.7). In isolated shaft fractures, active range of shoulder motion is reduced while gentle passive motion is uncomfortable but usually tolerated. With displaced fractures, a clinical deformity is often obvious. The proximal fragment usually displaces upward and may tent the skin. The shoulder girdle is shortened and droops downward and forward. When viewed from the back, the scapula appears prominent or “winged.” Due to the close proximity of the clavicle to the subclavian vessels and brachial plexus, a careful neurologic and vascular examination must be performed and documented.

Imaging Studies

A simple AP and oblique x-ray of the clavicle will confirm the diagnosis of fracture in the vast majority of cases. To obtain an accurate evaluation of the fragment position, two projections of the clavicle are typically obtained: anterior-posterior view and a (25 to 45 degrees) cephalic tilt view. The AP view should include the upper third of the humerus, the shoulder girdle, and the upper lung fields, so that other fractures or a pneumothorax can be identified. In the AP view, the proximal fragment is typically displaced superiorly and posteriorly, while the distal fragment is inferior, shortened, and internally rotated. The cephalic tilt view brings the clavicle and acromial-clavicular joint away from the overlying bony anatomy. CT and MRI scans may be useful in sternoclavicular fractures and dislocations but are rarely necessary for diaphyseal fractures.

Treatment Paradigm

Most clavicle fractures in adults are managed nonoperatively. Nonsurgical treatment is indicated when fracture displacement is <12 to 15 mm, angulation is under 10 degrees, and translation is less than a bone diameter. Treatment consists of support for the upper extremity in a sling, shoulder immobilizer, or figure-of-eight clavicle strap to relieve pain. In adolescents, teens, and young adults, a figure-of-eight sling is simple and well tolerated. In adults, a sling or shoulder immobilizer is usually preferred. These treatment methods will not “reduce” a clavicle fracture; rather, they are intended to support the upper limb during the healing process. Within 2 to

3 weeks, most patients are able to remove their sling for simple activities of daily living, bathing, and hygiene. Serial radiographs usually show some callus by 3 weeks and substantial healing by 6 to 8 weeks. External support is discontinued when the patient has minimal pain and x-rays show progressive healing. Return to activities is dictated by local symptoms. Most patients can return to full activities by 12 weeks if the fracture is healed.

3 weeks, most patients are able to remove their sling for simple activities of daily living, bathing, and hygiene. Serial radiographs usually show some callus by 3 weeks and substantial healing by 6 to 8 weeks. External support is discontinued when the patient has minimal pain and x-rays show progressive healing. Return to activities is dictated by local symptoms. Most patients can return to full activities by 12 weeks if the fracture is healed.

FIGURE 1.7 Clinical appearance of the shoulder and chest wall following a motorcycle accident that fractured the clavicle. |

Until the turn of this century, the indications for internal fixation of clavicle fractures were very limited. Most major orthopedic textbooks supported surgery for open fractures, those with vascular compromise or progressive neurologic deficits, as well as in patients with scapulothoracic dissociation, or displaced pathologic fractures. Not surprisingly, these conditions represent a small minority of clavicle fractures seen in clinical practice. Current indications for clavicular surgery, based on recent randomized clinical trials, support the use of internal fixation in adults when there is shortening, displacement, or translation <15 to 20 mm. Other strong indications for clavicular surgery include complex ipsilateral injuries to the scapula or proximal humerus, displaced group 2 type 2 lateral clavicle fractures, and symptomatic nonunion.

Timing of Surgery

Whereas open clavicle fractures, and those with neurovascular compromise require immediate treatment, the vast majority of closed displaced fractures that require surgery can be done electively during the first week after injury. Patients with other injuries that require early surgery and who remain hemodynamically stable may benefit from early internal fixation. However, in most seriously injured patients with a displaced clavicle fracture, internal fixation should be delayed until the patient’s condition has been optimized.

Surgical Tactic

There are two methods of internal fixation for clavicle fractures: intramedullary nailing and plate osteosynthesis. The rationale for intramedullary nailing is the relative ease of the procedure with minimal soft-tissue stripping leading to high rates of union and favorable functional outcomes. However, the S-shape curve in the clavicle, its small medullary canal, and the presence of fracture comminution limit its use. By far, the most common method of treatment for displaced clavicle fractures in adults is plate fixation. With this method of treatment, stable internal fixation with restoration of length, rotation, and alignment can be achieved allowing early range of shoulder motion and rehabilitation of the upper limb. Furthermore, recent advances in internal fixation using locking plate designs may also improve results. Most manufacturers now make contoured clavicle-specific plates, which further improve reduction and fixation (Fig. 1.8).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree