CHAPTER THREE CERVICAL SPINE

AXIOMS IN ASSESSING THE CERVICAL SPINE

INTRODUCTION

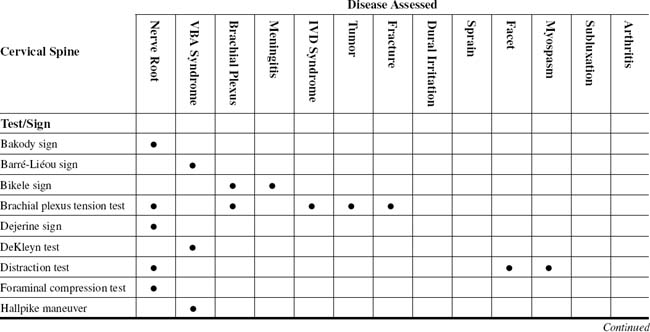

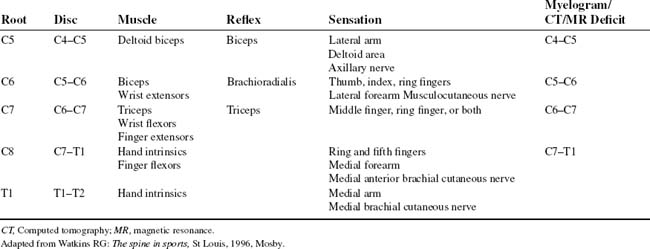

The nerve roots in the neck are particularly vulnerable to injury because of their relatively horizontal position in comparison with those of the lumbar spine. Stretching of the spinal cord itself is greatest at the cervical spine, which also predisposes the cord and nerve roots to trauma (Tables 3-1 and 3-2).

TABLE 3-2 CERVICAL SPINE CROSS-REFERENCE TABLE BY SYNDROME OR TISSUE

| Arthritis | |

| Brachial plexus | |

| Dural irritation | |

| Facet | |

| Fracture | |

| Intervertebral disc syndrome | |

| Meningitis | |

| Myospasm | |

| Nerve root | |

| Sprain | |

| Subluxation | |

| Tumor | |

| Vertebrobasilar artery syndrome |

Many provocative tests can be used for the cervical spine. The anatomic structures commonly tested are dural tension, foraminal and vertebral canal patency, and muscle, tendon, or ligamentous injuries (Table 3-3). During investigation of the upper extremity, the examiner must differentiate between canal or nerve root lesions by physical examination and, if necessary, electrodiagnostic studies. Cervical spine canal stenosis, whether of bony or soft-tissue origins, can cause lower-extremity signs and symptoms. Most notable is long tract pain, or rhizalgia, appearing in an ipsilateral leg with a cervical nerve root lesion (Table 3-4).

TABLE 3-3 COMMON PROVOCATIVE TESTS TO EVALUATE THE SPINE

| Provocative Test | Anatomic Structures Being Tested | Positive Finding(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Cervical Spine | ||

| Jackson compression test | Dural sheath, nerve root, spinal nerve | Radicular pain |

| Spurling compression test | Dural sheath, nerve root, spinal nerve | Radicular pain |

| Maximal foraminal compression test | Dural sheath, nerve root, spinal nerve | Radicular pain |

| Distraction test | Dural sheath, nerve root, spinal nerve | Relief of radicular pain |

| Shoulder depression test | Dural sheath, nerve root, spinal nerve, brachial plexus | Radicular pain to one or more dermatomes |

| E.A.S.T. test | Subclavian artery | Vascular compromise |

| Eden test | Scalene musculature | Radiculopathy to multiple dermatomes or vascular compromise |

| Thoracic Spine | ||

| Wright hyperabduction test | Pectoralis minor | Vascular compromise, subclavian artery, TOS |

| Tests for anterior thoracic wall | Peripheral nerve, muscles | Radicular pain, dull ache |

| Lumbar Spine | ||

| Straight leg raise | Dural sheath, nerve root, spinal nerve | Radiculopathy to one dermatome usually |

| Braggard test | Dural sheath, nerve root, spinal nerve | Radiculopathy to one dermatome usually |

| Bekhterev (Bechterew) test | Dural sheath, nerve root, spinal nerve | Radiculopathy to one dermatome usually |

| Neri bow string test | Dural sheath, nerve root, spinal nerve | Radiculopathy to one dermatome usually |

E.A.S.T., Elevated arm stress test; TOS, thoracic outlet syndrome.

From Greenstein GM: Clinical assessment of neuromusculoskeletal disorders, St Louis, 1997, Mosby.

TABLE 3-4 CLASSIFICATION OF POST–SPINAL CORD INJURY PAIN STATES

| Acute Phase Pains | Chronic Phase Pains |

|---|---|

Adapted from Beric A: Post-Spinal Cord Injury Pain States, Anesthesiol Clin North Am 15(2):445-463, 1997.

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 3-1 CERVICAL SPINE PAIN

Differential diagnostic possibilities of cervical spine pain include:

ESSENTIAL CLINICAL ANATOMY

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 3-3 CATEGORIES OF INTRACTABLE SPINAL CORD INJURY PAIN

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 3-4 NEURAL RESPONSES

Pathologic neural responses to cervical injury can be grouped into four categories:

The intervertebral discs are fibrocartilaginous flattened structures interposed between adjacent vertebral bodies. Each disc consists of a gelatinous inner region (i.e., the nucleus pulposus), surrounded by a solid ring of stiffer material (i.e., the annulus fibrosus).

ESSENTIAL MOTION ASSESSMENT

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 3-5 VERTEBRAL MUSCLES

The vertebral muscles are divided into two large groups:

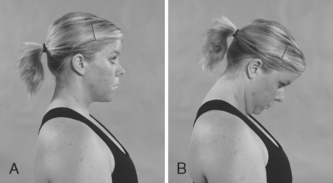

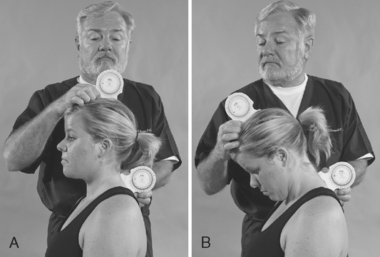

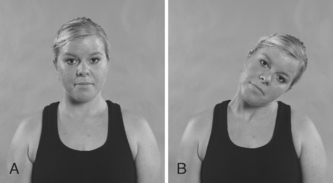

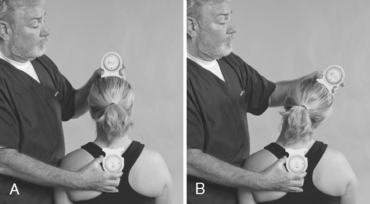

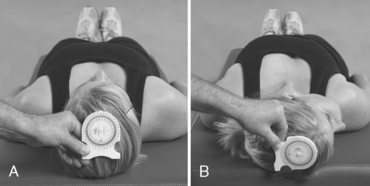

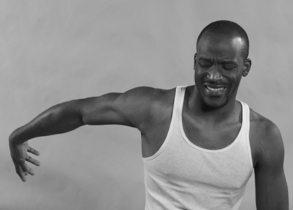

During a cervical spine range-of-motion assessment, the examiner should examine active then passive movements. For flexion, the patient brings the chin onto the chest; for extension, the patient bends the head backward as far as possible. For lateral flexion, the patient brings an ear toward the shoulder, first on one side and then on the other. For rotation, the patient looks over one shoulder and then the other. Repeating the movements while applying gentle pressure over the vertex of the skull may trigger pain or paresthesia in the arm if a critical degree of narrowing exists at an intervertebral foramen. In evaluating cervical spine range of motion, the examiner observes not only the total range of movement, but also the smoothness and comfort with which the patient accomplishes the motions (Figs. 3-1 to 3-8).

ESSENTIAL MUSCLE FUNCTION ASSESSMENT

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 3-6 CERVICAL SPINE MUSCLE STRENGTH

To evaluate cervical spine muscle strength, the patient takes the following actions:

The intrinsic longitudinal vertebral muscles, placed more superficially, are collectively called the erector spinae. The cervical region contains elongated muscles originating from the spinous process (the splenius muscles) and others from the transverse processes (the semispinalis muscles). The suboccipital muscles are a special group of muscles linking the atlas, the axis, and the base of the skull.

ESSENTIAL IMAGING

Plain-Film Imaging

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 3-8 CERVICAL SPINE PLAIN FILM SERIES

The typical cervical spine plain-film series consists of the following:

Specific views are used to evaluate complex regions of anatomy or spinal placement at extremes of motion (Box 3-1).

BOX 3-1 ACCEPTED ADDITIONAL CERVICAL SPINE PLAIN-FILM IMAGING

Data from Greenstein GM: Clinical assessment of neuromusculoskeletal disorders, St Louis, 1997, Mosby.

In assessing the sagittal diameter of the spinal canal, on a lateral view, the shortest distance from the posterior aspect of the vertebral body to the spinolaminar line is measured. The distance between the posterior aspect of the dens and the posterior cervical line is measured at C1. The ranges for diameter by level are listed in Table 3-5.

TABLE 3-5 ACCEPTED SAGITTAL CANAL DIAMETER OF THE CERVICAL SPINE

| Level | Diameter (mm) Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|

| C1 | 16 | 31 |

| C2 | 14 | 27 |

| C3 | 13 | 23 |

| C4 to C7 | 12 | 22 |

Adapted from Greenstein GM: Clinical assessment of neuromusculoskeletal disorders, St Louis, 1997, Mosby.

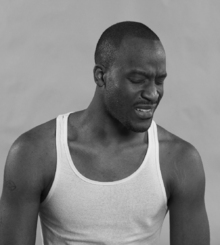

BAKODY SIGN

SHOULDER ABDUCTION RELIEF SIGN/TEST—CERVICAL FORAMINAL COMPRESSION TEST

Assessment for Cervical Nerve Root Compression

Comment

Cervical radiculopathy is more common than cervical myelopathy. Cervical radiculopathy consists of pain and neurologic dysfunction produced by irritation or injury to a spinal nerve. The injury may be caused by a herniated cervical disc, cervical foraminal stenosis, tumors, fractures, or dislocations. The pathognomic characteristic of cervical radiculopathy is pain in the distribution of nerve (Table 3-6).

PROCEDURE

BARRÉ-LIÉOU SIGN

Assessment for Vertebral Artery Syndrome

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 3-10 VERTEBRAL ARTERY COMPRESSION

Three mechanisms of vertebral artery compression are:

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 3-11 TRAUMA TO THE VERTEBRAL ARTERY

Three areas in which the vertebral artery is most susceptible to trauma:

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 3-12 CLASSIFICATION OF LOCKED-IN SYNDROME

Locked-in syndrome is subdivided based on the extent of motor impairment:

ORTHOEPDIC GAMUT 3-13 THE AMERICAN CONGRESS OF REHABILITATION MEDICINE (1995) DEFINITION OF LOCKED-IN SYNDROME