Chapter 4 Care of the Elderly Patient

Geriatric Assessment

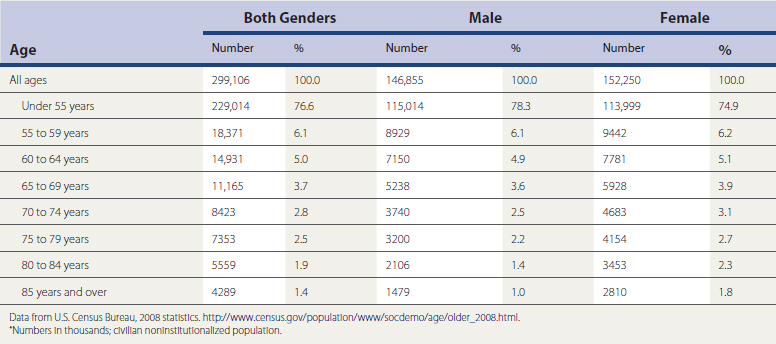

Longer life spans and aging “baby boomers” will double the population of Americans age 65 years and older over the next 25 years. The dramatic increase in life expectancy in the United States is the result of improved medical care and prevention efforts. In 2006, persons 65 years or older numbered 37.3 million and represented 12.4% of the U.S. population, about one in every eight Americans. The population 65 and over increased from 35 million in 2000 to about 40 million in 2010, a 15% increase, and then will increase to 55 million in 2020, a 36% increase for that decade. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2007), by 2030 there will be about 71.5 million older persons, more than twice their number in 2000 and about 20% of the U.S. population (Table 4-1).

There has been a significant shift in the leading causes of death for all groups from infectious disease and acute illnesses to chronic diseases and degenerative illnesses. Of the elderly population, approximately 8% experience severe cognitive impairment, 20% have chronic disabilities and vision problems, and 33% have restrictions in mobility and hearing loss (Freedman et al., 2002). There are also the predictable age-related structural and physiologic changes that occur with aging. External factors such as diet, occupation, social support, and access to health care can significantly influence the extent and speed of the physiologic decline (Arif et al., 2005; Sarma and Peddigrew, 2008; Tourlouki et al., 2009).

A comprehensive geriatric assessment is a systematic approach to the collection of patient data. The approach varies greatly, from single-physician evaluation with referral as needed, to full teams of professionals evaluating all patients. The geriatric assessment can assist in developing an individualized approach to each patient (Table 4-2). It is imperative to recognize the unique “blueprint” of what characterizes each elderly patient, including age, ethnicity, education, religious or spiritual beliefs, traditions, diet, interests/hobbies, daily routines, medical illness and disabilities, language barriers, functional status, marital status, sexual orientation, family and social support, occupation, life experiences, and socioeconomic position.

Table 4-2 Goals of Geriatric Assessment

3. Provide a long-term solution for “difficult to manage” patients with multiple physicians, recurrent emergency department visits, and hospital admissions with poor follow-up. |

Medical Assessment

Four shared risk factors—older age, baseline cognitive impairment, baseline functional impairment, and impaired mobility—have been identified within the five most common geriatric syndromes: pressure ulcers, incontinence, falls, functional decline, and delirium (Inouye et al., 2007). It is important that health care providers familiarize themselves with the common geriatric body area or system disorders that can directly influence these risk factors. Understanding the basic mechanisms involved in geriatric syndromes is essential to targeting therapeutic options.

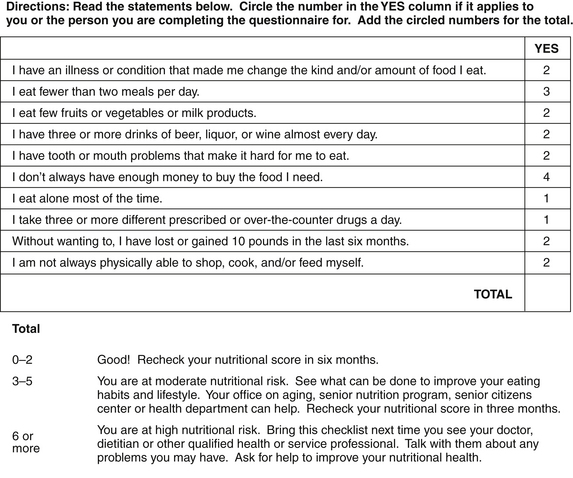

Nutritional evaluation is an integral part of the geriatric assessment. The type, quantity, and frequency of food eaten should be determined. Malnutrition and undernutrition can lead to health problems that include delayed healing and longer hospital stays. A reliable marker of nutritional problems is weight loss, specifically, more than 5% in the past month and 10% or greater weight loss in the last 6 months (Huffman, 2002). Clinicians should ask about any special diets (e.g., low carbohydrate, vegetarian, low salt) or self-prescribed “fad” diets. A nutritional screen can aid in further assessment of the patient’s nutritional health and help guide interventions (Figure 4-1). Additional questioning should include weight loss and change of fit in clothing; amount of money spent on food; and accessibility of grocers with a variety of fresh foods.

Social Assessment

It is important to assess the patient’s living situation and social support when performing a geriatric assessment. The living situation should be evaluated for potential hazards, especially if the patient is identified as being at risk of falling. The social assessment also includes questions about financial stressors and caregiver concerns. Advance planning is a key component of the assessment and includes clarifying the patient’s values and setting goals for care in case of future incapacity, including identifying the patient’s “power of attorney” for health care.

Summary

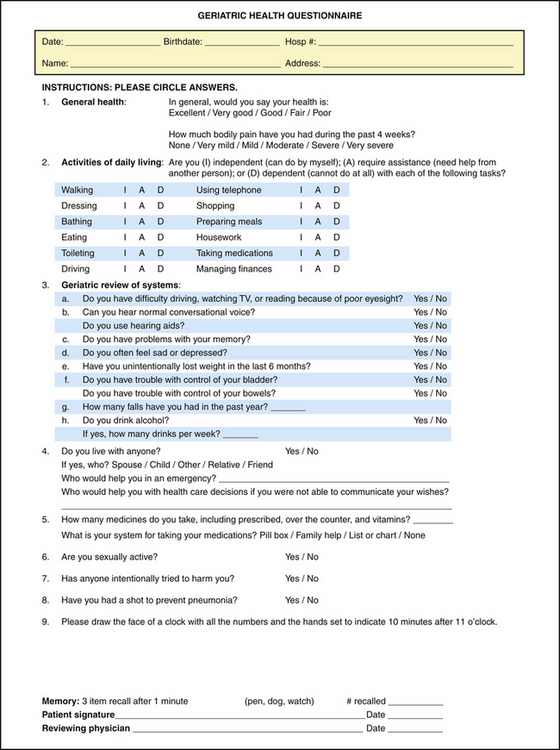

The key to a successful geriatric assessment is to establish trust and effective communication between the patient and the physician. Allotting for adequate time during appointments and, if needed, scheduling frequent office visits are essential to the gathering of information. Inquiring about recent socioeconomic changes, functional losses, or life transitions is also important. The physician should obtain the patient’s medical records before the first visit. A questionnaire targeted to the geriatric assessment domains should be completed by the patient, with family assistance if needed (Figure 4-2). Language, education, social support, economic status, and cultural/ethnic factors play a vital role in the patient’s health care outcome. A multidisciplinary approach is used to interventions and management. Preserving function and maintaining quality of life are the primary goals of the geriatric assessment (Miller et al., 2000).

Falls

Risk Factors

The multiple risk factors for falling can be categorized as intrinsic or extrinsic. Intrinsic risk factors include age-related physiologic changes and diseases that affect the risk of falling (Table 4-3). Extrinsic risk factors include medications and environmental obstacles. The risk of falling increases significantly in people with multiple risk factors. A prospective study found that 19% of older patients with one risk factor have a fall in a given year, compared with 60% of older patients with three risk factors (Tinetti et al., 1998).

Table 4-3 Intrinsic Risk Factors for Falls

| Age-related changes in: Age >80 years Cognitive impairment Depression Functional impairment History of falls Visual impairment Gait or balance impairment Use of assistive device Arthritis Leg weakness |

Falls Assessment

Falls assessment should include a multifactorial evaluation beginning with the circumstances surrounding the fall(s), associated symptoms, risk factor assessment, and medication history (Table 4-4). The physician should ask about the environment (e.g., indoors or outdoors, dark or well lighted, time of day), environmental obstacles (e.g., throw rugs, door thresholds, stairs), and footwear worn at the time. The history should also include questions about prodromal symptoms (e.g., lightheadedness, dizziness), if there was a loss of consciousness or other symptoms of arrhythmias (i.e., palpitations). If available, obtain information from a witness. The evaluation should also include questions about risk factors, functional abilities and medication history (AGS et al., 2001).

Table 4-4 Initial Evaluation of Falls

| History |

| Circumstances of fall Presence of risk factors Medical conditions Medication review Functional abilities |

| Physical Examination |

| Postural blood pressure Visual acuity Cardiovascular examination: rhythm, murmurs Neurologic examination: strength, proprioception, cognition Musculoskeletal examination: range of motion (ROM), joint abnormalities Gait and balance assessment |

| Diagnostic Studies |

| None required routinely. |

Postural blood pressure and pulse are important assessments in the examination. Up to 30% of older persons have orthostatic hypotension, and although some may be asymptomatic, others become lightheaded and dizzy (Luukinen et al., 1999). The musculoskeletal examination should focus on range of motion in the legs, inflammatory or degenerative conditions of the leg joints, kyphosis, and abnormalities of the feet. The neurologic examination should include proprioception, coordination, muscle strength, and cognition. The cardiovascular examination should focus on detecting potential causes of falls (e.g., arrhythmias, aortic stenosis). Visual acuity and hearing should be assessed. Disturbances in gait and balance can be identified through the patient or caregiver’s direct report or a simple office-based assessment, such as the “get up and go” test (Podsiadlo and Richardson, 1991). This test may be scored, timed, or used as an overall assessment of the patient’s gait, stability, balance, and strength. The patient is asked to stand from a seated position, walk about 10 feet (3 meters), turn around, walk back, and sit down again. If the patient needs to push off the chair or rock back-and-forth several times to arise, leg strength is diminished. The task should be completed within 10 seconds. Gait abnormalities, such as poor step height, decreased stride length, and shuffling, may be observed. A wide-based stance and slow, multiple-point turning may reveal poor balance.

Management

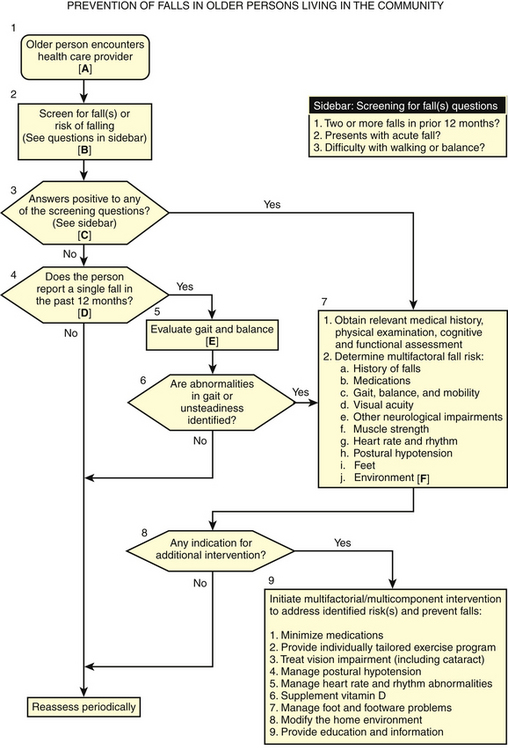

Evidence has demonstrated that a multifactorial approach and intervention strategy is needed to reduce the rate of falling in older patients (Figure 4-3). Because one of the most modifiable risk factors is medication use, medication review is a key component of management (Hanlon et al., 1997). The review should focus on decreasing the dose or discontinuing sedating medications. If orthostasis is present, adjustment of diuretics and antihypertensive medications should be considered. The role of vitamin D in fall prevention is questionable. Although, it probably does not decrease the risk of falls, except in patients with low levels of vitamin D, supplementation should be started in patients with osteopenia or osteoporosis (Gillespie et al., 2009).

Figure 4-3 Practice guideline for the prevention of falls in older persons.

(From American Geriatrics Society (AGS), British Geriatrics Society, and American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Panel on Falls Prevention: Guideline for the prevention of falls in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001;49:664-672.)

KEY TREATMENT

persons, particularly those with visual impairment and multiple risk factors (Gillespie et al., 2001; Stevens et al., 2001).

Elder Abuse

Definition

The National Center on Elder Abuse (2009) defines elder abuse as “a term referring to any knowing, intentional, or negligent act by a caregiver or any other person that causes harm or a serious risk of harm to a vulnerable adult.” Although terms vary across states, elder abuse can be generally categorized into several types: physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, exploitation, neglect, self-neglect, and abandonment (Table 4-5). Elder abuse is also classified by its setting. Domestic abuse occurs in the home of the victim. Institutional abuse occurs in a nursing home, hospital, assisted-living center, or group home.

Table 4-5 Elder Abuse: Definitions

| Physical abuse: Inflicting, or threatening to inflict, physical pain or injury on a vulnerable elderly person, or depriving the person of a basic need. Emotional abuse: Inflicting mental pain, anguish, or distress on an elderly person through verbal or nonverbal acts. Sexual abuse: Nonconsensual sexual contact of any kind. Exploitation: Illegal taking, misuse, or concealment of funds, property, or assets of a vulnerable elder. Neglect: Refusal or failure by those responsible to provide food, shelter, health care or protection for a vulnerable elder. Abandonment: The desertion of a vulnerable elder by anyone who has assumed the responsibility for care or custody of that person. Self-neglect: Characterized as the behavior of an elderly person that threatens his or her own health or safety. |

Modified from National Center on Elder Abuse. http://www.ncea.aoa.gov/NCEAroot/Main_Site/Index.aspx. October 2009.

Risk Factors

Awareness of risk factors for abuse can increase the chance of identification and early intervention. Although research is ongoing, several characteristics of both the victim and the abuser should trigger further screening questions. Risk factors associated with the victim include shared living situations, history of dementia, and social isolation. Perpetrator risk factors include a history of mental illness (specifically depression), alcohol abuse, and financial dependency (Lachs and Pillemer, 2004).

Screening

There is no consensus that asymptomatic patients should be screened for elder abuse. The American Medical Association (AMA, 1992) suggests that all outpatients be screened for family violence, but the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2009) concluded that there was insufficient evidence for or against screening for older adults or their caregivers for elder abuse. Patients should be screened if there is a suspicion of elder abuse. The questions should be open-ended, nonthreatening, and asked in a variety of ways to assess for the different forms of elder abuse (Table 4-6). A positive response should be followed by more direct questions as to the nature of the abuse. Direct questioning by physicians has been shown to increase reporting (Oswald et al., 2004).

Table 4-6 Screening Questions for Elder Abuse

| Are you afraid of anyone at home? Are you alone a lot? Has anyone at home ever hurt you? Has anyone taken anything that was yours without asking? Does anyone at home make you uncomfortable or afraid? Has anyone ever forced you to sign a document that you did not understand? Are you kept isolated from friends or relatives? |

Clinical Manifestations

Certain behavioral and physical signs should raise suspicion for elder abuse. Behavioral signs in the caregiver include answering for the patient, insisting on being present for the entire visit, failing to offer assistance, and displaying indifference or anger. Behavioral signs in the elderly patient include poor eye contact, hesitation to talk openly, or fearfulness toward the caregiver. Other indicators of possible abuse include confusion, paranoia, anxiety, anger, and low self-esteem. Physical signs that may signal neglect include poor hygiene, malnutrition, dehydration, pressure ulcers, and injuries (Table 4-7). Medication nonadherence may also be a warning sign for abuse.

Table 4-7 Physical Signs of Elder Abuse

| General |

| Weight loss Dehydration Poor hygiene |

| HEENT |

| Traumatic alopecia Poor oral hygiene Absent hearing aids, dentures, or eyeglasses Subconjunctival or vitreous hemorrhage |

| Skin |

| Hematomas Welts Burns Bruises Bites Pressure sores |

| Genitorectal |

| Inguinal rash Fecal impaction |

| Musculoskeletal |

| Fractures Contractures |

HEENT, Head, ears, eyes, nose, throat.

Management

Because the cause of elder abuse is often multifactorial, management involves a multidisciplinary approach with social workers and legal, financial, and APS representatives. The immediate management is determined by the safety and capacity assessments. Is the patient in any immediate danger? If so, acute hospitalization, safe home placement, and a protective court order may be indicated. If the patient lacks capacity, the physician should work with APS on options, including guardianship, financial management resources, and order of protection if indicated. In other cases, management should focus on utilizing community resources to maintain the patient in the least restrictive environment. The emphasis is to decrease social isolation and caregiver stress. Interventions can include respite care, home health or custodial services, counseling, and drug or alcohol rehabilitation.