Chapter 17 Care of the Adult HIV-Infected Patient

Box 17-1 presents a timeline on HIV/AIDS and antiretroviral therapy.

Box 17-1 Key Events in HIV/AIDS Crisis and Development of Therapy

| 1959 | African man dies of a mysterious viral illness, now recognized as the ancestor of HIV. |

| 1981 | CDC reports “gay-related immune deficiency” (GRID) as the cause of outbreaks of deaths of gay men in California and New York. |

| 1983 | |

| 1985 | |

| 1987 | Advent of zidovudine (AZT or ZDV) as first treatment for HIV infection. |

| 1992 | Combination therapy with zalcitabine (ddC) approved. |

| 1993 | |

| 1996 | |

| 1997 | |

| 1998 | |

| 2001 | First-entry inhibitor, enfuvirtide (Fuzeon), is developed. |

| 2004 | First generic antiretroviral approved by FDA. |

| Combination drugs Truvada (emtricitabine and tenofovir) and Epzicom (abacavir and lamivudine) and new protease inhibitors Reyataz and Lexiva become available. | |

| 2005 | As side effects of chronic HAART identified, experts recommend delay of HAART initiation. |

| 2006 | Current scientific opinion holds origin of HIV in the meat and bites of African monkeys. |

| 2009 | HIV genome is decoded. |

Epidemiology

About 33 million people worldwide are living with HIV/AIDS in 2007. Of these, 2.7 million have been newly infected, and 2 million people have died of HIV/AIDS. Developing countries account for more than 95% of these infections (UN AIDS, 2007). Since 1981, an estimated 1.7 million people have been infected; more than 1 million people in the United States are currently living with HIV/AIDS; and 565,927 have died of AIDS. The number of deaths has declined by 17% between 2003 and 2007. From 2004 to 2007, there has been an increase of 15% in the incidence of HIV/AIDS cases in the United States. This increase occurred mainly in persons age 40 to 44, who accounted for 15% of all HIV/AIDS cases, likely caused by both changes in reporting systems and increased HIV testing.

Modes of Transmission and Relative Risk

The three main modes of transmission of HIV are as follows:

Pathophysiology

Life Cycle of HIV and Relevance to Treatment

Step 1

The HIV adheres to and sequentially binds with the host CD4+ cell receptor and a co-receptor (CCR5 or CXCR4). Most wild-type viruses have the CCR5 co-receptor, but with prolonged infection, more and more CXCR4 appears. Binding with the host CD4+ cell allows the virion to enter the cell and, aided by the co-receptor, to release the two copies of the viral RNA. Drugs called fusion inhibitors interrupt this step.

Classification and Staging of HIV/AIDS

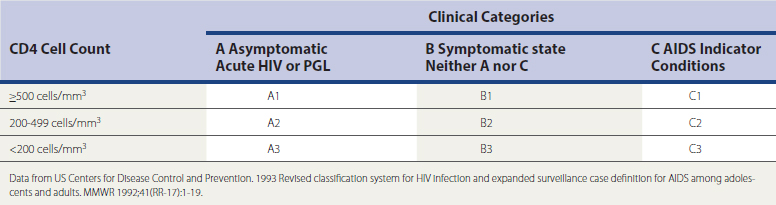

The two classification systems currently in use to monitor the severity of HIV illness and assist with its management have been developed by the CDC (Table 17-1) and the World Health Organization (WHO) (Box 17-2). The CDC classification, last modified in 1993, uses CD4+ counts and specific HIV-related conditions, whereas the WHO classification, developed in 1990 and revised in 2007, is guided by clinical observations and can be used in settings where access to CD4+ tests is unavailable.

Box 17-2 WHO Clinical Staging of HIV/AIDS

Modified from World Health Organization. Case definitions of HIV for surveillance and revised clinical staging and immunological classification of HIV related disease in adults and children. Geneva, WHO, 2007. www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/HIV.