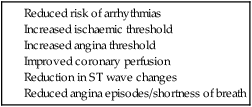

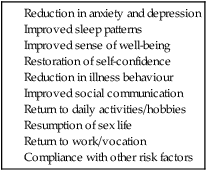

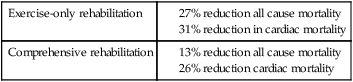

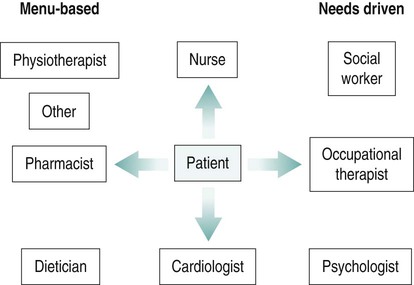

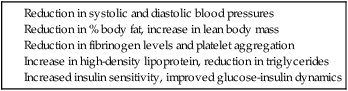

Over the last two decades of the twentieth century in the UK, there was a decline in the death rates from CHD. In a study by Unal et al. (2004), the authors concluded that 58% of CHD mortality decline in the 1980s and 1990s was owing to a reduction in major risk factors, primarily smoking. The remaining 42% of the decline in mortality was explained by treatments, including secondary prevention. The WHO defines cardiac rehabilitation as: The Cochrane Review 2004 (Jolliffe et al. 2004) (Table 8.1) established the importance of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation. Cardiac mortality was reduced by 31% in the exercise-only cardiac rehabilitation and by 26% in comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation groups. Table 8.1 Cochrane review 2004: The WHO estimates that around 6% of all disease burden and around 30% of CHD burden to be caused by physical inactivity (WHO 2010). Physical activity levels are low in the UK. The Health Survey for England data (2008) show that only 39% of men and 29% of women meet the government guidelines of 30 minutes of moderate physical activity five or more times a week. The proportion of both men and women who met the recommendations decreased with age. Therefore, structured exercise as a therapeutic intervention is essential to the cardiac rehabilitation programme. Incidence of CHD tends to be higher in men; however, this difference decreases with increasing age. According to the BHF statistics 2010 (BHF 2010), every year 44,000 women in the UK have a MI. Uptake of cardiac rehabilitation among women is low. When women attend cardiac rehabilitation programmes, the outcomes are as good as, or better than, for men. Their need may be greater as they suffer greater loss of function in relation to return to work, activity and sexuality, and experience high levels of anxiety and depression. More gender-specific information, individualised and flexible programmes, and suitable environment are required to address the specific needs of this group. Phase II: early post-discharge period. Phase III: supervised outpatient programme, including structured exercise. • assessment of physical, psychological and social needs; • negotiation of a written informal plan for meeting these identified needs; • initial advice on lifestyle, e.g. smoking cessation, physical activity (including sexual activity), diet, alcohol consumption and employment; • education about prescribed medication, its benefits and possible side effects; • involvement of relevant informal carer; • provision of locally written information about cardiac rehabilitation; This service shows variation in different regions and can vary from as little as a telephone helpline to group sessions or individual appointments (Figure 8.1). The National Service Framework recommendation includes: • comprehensive assessment of cardiac risk, including physical, psychological and social needs for cardiac rehabilitation, and a review of the initial plan to meet these needs; • provision of lifestyle advice and psychological interventions according to the agreed plan by the multi-disciplinary team; • maintaining involvement of relevant informal carer; • risk stratification and identification of the high-, medium- and low-risk patient for exercise; • individualised progressive exercise prescription and supervised exercise sessions which vary from 4–12 weeks in different regions; • re-evaluation of risk factors for CHD and health promotion advice and education (Figure 8.2). • psychosocial interventions, such as stress management, counselling and vocational guidance. The cardiac rehabilitation package individualised for each patient requires expertise and skills from a multi-disciplinary collaborative team of professionals (Figure 8.4). The team includes a cardiologist and staff from nursing, physiotherapy, dietetics, pharmacy, occupational therapy and psychology with training in cardiac rehabilitation. Continuation of care in the community involves the primary healthcare team that is the general practitioner and cardiac nurse, phase IV exercise specialist and a link from a local cardiac patient support group (Figure 8.3). Research confirms that exercise training improves physical performance (exercise tolerance, muscular strength and symptoms), psychological functioning (anxiety, depression and well-being), and social adaptation and functioning in cardiac patients (Tables 8.2 and 8.4). It shows a reduction in mortality, morbidity, recurrent events and hospital readmissions. It is also found to have a positive impact on patients’ physical ability to exercise (Table 8.3). Therefore, exercise training as a therapeutic intervention is central to the cardiac rehabilitation programme. Table 8.2 In CHD patients, the increase in VO2 max is predominantly a result of peripheral adaptations. Central changes are associated with long periods of high intensity training. Although central changes have been shown with high intensity training in CHD patients in some studies, in the conventional cardiac rehabilitation programmes this regime is not suitable. Physical performance improvements are better seen in patients with low exercise tolerance. • a detailed history of the present condition and clinical presentation; • previous levels of activity and exercise; • physical limitations and disabilities; • risk factor assessment/profile; • screening for relative contraindications; • psychosocial assessment: objectives, beliefs, knowledge, interests, ethnicity; • Resting SBP >200 mmHg or resting diastolic BP (DBP) >110 mmHg. • Orthostatic BP drop >20 mmHg with symptoms. • Acute systemic illness or fever. • Uncontrolled atrial or ventricular arrhythmias. • Uncontrolled sinus tachycardia. • Uncompensated chronic heart failure. • Active pericarditis or myocarditis. • Resting ST segment displacement >2 mm on electrocardiograph (ECG).

Cardiac rehabilitation

Background

What is cardiac rehabilitation?

Research evidence for cardiac rehabilitation

meta-analyses of 8440 myocardial infarction, revascularisation and ischaemic heart disease patients

Exercise-only rehabilitation

Comprehensive rehabilitation

Evidence for physical activity and exercise

Patient groups in cardiac rehabilitation

Special needs groups

Women

Components of cardiac rehabilitation

Operation and delivery

Phase I: Inpatient period

Phase II: Early post-discharge period

Phase III: Supervised outpatient programme, including structured exercise

Cardiac rehabilitation team

Benefits of exercise training

Physiological adaptations to exercise training in healthy individuals and coronary heart disease patients

Adaptations at submaximal level of aerobic exercise

Increase in VO2 max

Assessment for exercise prescription

Contraindications to exercise