Blood Management

E. Michael Keating and Trevor R. Pickering

Key Points

Introduction

Primary hip replacement and revision hip replacement surgery are often associated with significant blood loss and risk of allogeneic transfusion. Although this risk has changed dramatically over the past 15 years,1 a certain minimum amount of blood loss will always be due to the nature of hip replacement surgery, as bone bleeding is unsuitable for conventional cautery. The risk of blood loss is particularly high in areas consisting of inflammatory tissues. Furthermore, hip arthroplasty procedures are often performed on geriatric patients whose vessels are fragile, and who may be less tolerant of acute blood loss anemia. Blood loss from primary total hip replacement surgery has been reported to range from 500 to 2000 mL, with an average drop in hemoglobin of 4.0 ± 1.5 g/dL reported in the literature; this has not improved in recent years.1–5 Blood loss of this magnitude indicates that careful planning is required to decrease transfusion risk.6

Basic Science

In a multicenter study, Bierbaum and associates described blood usage in 9482 patients undergoing total joint replacement surgery.7 They found greater blood loss in patients who were in the revision joint replacement category. A total of 5741 patients (61%) had predonated autologous blood, of which 45% (4464 units) was not used and was discarded. In this study, patients undergoing primary hip or knee arthroplasty had the greatest number of wasted units. Also noted were 503 patients (9%) who predonated blood and received their autologous units, yet still required an additional allogeneic blood transfusion.7 Patients with a preoperative hemoglobin of 13 g/dL or less and those undergoing revision total joint replacement had the highest allogeneic transfusion risk.7 An Orthopaedic Surgery Transfusion Hemoglobin European overview study of 3945 patients in Europe showed similar results. In this study, 75% of patients received transfusions, 35% received only autologous blood, and 26% received only allogeneic blood.8 In the European study, allogeneic transfusions were associated with an increased wound infection rate of 4.2% versus 1%.8 Findings in both of these studies showed that patients requiring allogeneic transfusion had a longer hospital stay. Both studies also found that preoperative hemoglobin levels less than 13 g/dL increased allogeneic transfusion risk by about four times.7,8

Generally, the public has expressed its concerns regarding the safety of the blood supply with respect to the risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission through blood transfusion (Table 23-1).9–11 In the United States, transmission of disease through blood transfusion is less than it has ever been. An estimate of the risk is 1 in 1.6 million units for hepatitis C transmission and 1 in 1.8 million units for HIV transmission.10 However, in a national telephone survey, a substantial portion of responders did not consider the U.S. blood supply safe.9 Beyond the risks related to viral disease transmission, it is known that exposure to leukocytes in allogeneic blood can cause immunosuppression. The importance of this has not yet been clearly defined.12 The most serious immediate risks following allogeneic blood transfusion include ABO mismatch secondary to administrative error and transfusion-related lung injury.

Table 23-1

Risk of Infection From Blood Transfusion

| Agent | Risk |

| Virus | |

| HIV | 1 in 1,800,00010 |

| HCV | 1 in 1,600,00010 |

| HBV | 1 in 220,00010 |

| Bacteria | |

| Red cells | 1 in 500,00011 |

| Platelets | 1 in 200011 |

| Acute hemolytic reaction | 1 in 250,00011 |

| Delayed | 1 in 100011 |

| Transfusion lung injury | 1 in 800011 |

HBV, Hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Data from Busch MP, Kleinman SH, Nemo GJ: Current and emerging infectious risks of blood transfusions. JAMA 289:959–962, 2003; Goodnough LT: Risks of blood transfusion. Crit Care Med 31(Suppl):S678–686, 2003.

Current Controversies and Future Directions

Preoperative Evaluation

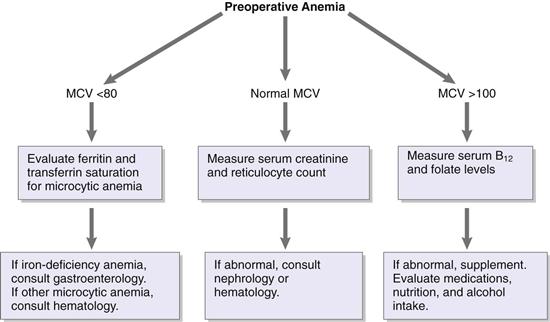

Because of the significant blood loss associated with hip replacement surgery, application of a blood management program is appropriate.1 This program should encompass areas such as preoperative evaluation protocols, surgical techniques, and intraoperative interventions, where appropriate. Most surgeons would not think of taking a patient to the operating room for major surgery without performing a thorough evaluation of the heart and lungs. Likewise, a clinical care pathway for the detection, evaluation, and treatment of preoperative anemia in surgical patients would involve a hemoglobin level test done a minimum of 30 days before the scheduled surgical procedure. This would allow for evaluation and management of anemia before surgery. It should be kept in mind that anemia can be a symptom of significant illness that may preclude elective surgery (e.g., infection, hepatic or renal disease, cancer). Patients with a hemoglobin level below the normal range should undergo additional testing. Although any number of workup algorithms can be adopted, the surgeon should be comfortable recognizing basic patterns of major anemias on blood tests, so that a referral can be made as needed for further evaluation. This testing should include serum B12 and folate levels if the mean corpuscular volume (MCV) is greater than 100. If the MCV is found to be less than 80, additional testing should be performed to measure ferritin and transferrin saturation levels to identify iron deficiency or other causes of microcytic anemia. In the presence of iron deficiency, a gastrointestinal evaluation is recommended. If the patient has a low hemoglobin level and a normal MCV, the reticulocyte count and serum creatinine should be measured. If either is abnormal, then appropriate consultation should be obtained (Fig. 23-1). Anemia of chronic disease is a diagnosis of exclusion.1

Figure 23-1 A simplified algorithm for evaluating common causes of anemia from a routine preoperative blood laboratory test. Abnormalities without a clear cause require additional workup and may indicate significant illness or chronic disease.

Preoperative Autologous Donation

Preoperative autologous donation is a blood conservation strategy that is widely used before elective orthopedic surgery is performed.13 However, evidence suggests that this practice is declining.1 The popularity of autologous donation can be partially attributed to its perceived safety and acceptance by the patient population, especially in light of public perception of the safety of the blood supply.13 Autologous blood does not eliminate all of the risks of blood transfusion. The risk of an untoward reaction from the transfusion is seen as an incidence of 20,000 to 30,000 units.14 The chance that autologous blood may be transfused to the wrong recipient is possible. The American College of Pathologists reporting that 1% of institutions surveyed issued allogeneic blood to the wrong patient on at least one occasion in 1 year, and half of those facilities had transfused autologous blood to the wrong patient. Other adverse events can occur in recipients of autologous blood, including febrile transfusion reactions and volume overload.15–17

Another problem with the use of preoperative autologous donation is preoperative anemia.18,19 When the patient donates blood, typically 2 units within 42 days of surgery, this donation has been shown to lower the patient’s preoperative hemoglobin and hematocrit levels by approximately 1.2 to 1.5 g/dL per donated unit.20 This preoperative anemia independently increases the need for perioperative transfusion.18–20 Hatzidakis and associates analyzed the risk factors of allogeneic transfusion in patients who had donated autologous blood.20 They reviewed 489 patients, 207 of whom underwent total hip replacement. They found that preoperative autologous donation reduced the need for allogeneic blood. They also reported that preoperative hemoglobin levels greater than 15 and patients with hemoglobin levels between 13 and 15 who were younger than 65 were at low risk for requiring allogeneic blood and did not benefit from preoperative donation.20 Billote and colleagues21 performed a randomized prospective study of preoperative autologous donations. These investigators found that an autologous donation was of no benefit for the nonanemic patient (preoperative hemoglobin >12) undergoing primary total hip replacement.

The cost-effectiveness of preoperative autologous donation has been questioned in large part as a result of the underuse of predeposited blood. Between 50% and 70% of predeposited blood is discarded; therefore, treatment of preoperative anemia may be more cost-effective than autologous donation.7

Preoperative Hematopoiesis

Preoperative hematopoiesis can be stimulated in total hip arthroplasty (THA) patients with the use of iron therapy and erythropoietin-α. Iron therapy has been used for many years; however, oral iron is poorly absorbed in the gut, is very slow-acting for hematopoiesis, and is much less effective than erythropoietin-α.13 Oral iron preparations are inexpensive; however, many patients do not tolerate these medications over the long term because of gastrointestinal side effects. Intravenous iron preparations, although very effective, have been associated with significant allergic reactions.

In patients with anemia of chronic disease, preoperative administration of erythropoietin-α has been shown to be a very effective means of improving the starting hemoglobin level before elective total hip replacement surgery. This preparation was initially used as an adjunctive method to improve autologous donation.22 It has been shown to be safe and effective in the treatment of preoperative anemia in orthopedic patients with anemia of chronic disease and a preoperative hemoglobin level between 10 and 13.3,22-25 In one randomized prospective study of 490 patients undergoing total hip replacement arthroplasty that compared preoperative autologous donation (PAD) with epoetin-α therapy, a smaller proportion of patients required allogeneic transfusion—12.9% compared with 19.2% in the PAD only group.26 This difference was not statistically significant (P = .078); however, it approached significance. When PAD, EPO, and the combination were studied, Bezwada and associates found that PAD and EPO combined were more effective in reducing allogeneic risk than was PAD or EPO alone.27 Despite its effectiveness, erythropoietin-α has been considered inconvenient because of its dosing regimen. Medicare fiscal intermediaries have approved the use of erythropoietin-α in patients undergoing elective surgery, with the following restrictions28: (1) the operation must be expected to cause loss of greater than 2 units of blood, (2) preoperative hemoglobin must be between 10 and 13 g/dL, (3) the patient must be unwilling or unable to donate autologous blood, and (4) the preoperative evaluation must suggest the presence of anemia of chronic disease.28 These stringent reimbursement requirements have made it more difficult for orthopedic surgeons to effectively treat preoperative anemia with erythropoietin-α. Studies have shown that the use of a blood conservation algorithm designed to predict which patients would likely need allogeneic transfusions, combined with use of a lower transfusion threshold, has been able to decrease the allogeneic risk of hip replacement patients to 2.8% without the use of an autologous donation program.6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree