Athlete with Knee Pain

Carolyn Saluti

INTRODUCTION

Running is an excellent activity to keep a person healthy. Many people choose to run because of its convenience and affordability. It has many health benefits, but along with the benefits, there are also injuries. Knee pain is a common symptom seen in runners with up to 50% of running injuries occurring at the knee.1 There are many etiologies of knee pain, but a good history and physical exam can differentiate between the causes.

FUNCTIONAL ANATOMY

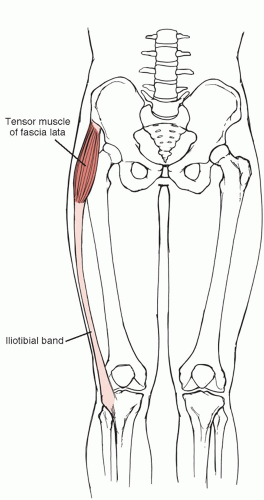

The tibiofemoral joint is the largest joint in the body (see Figs. 18.1 and 18.2). The femur sits on the articular surface of the tibia with the meniscus acting as a cushion between the two bones. The menisci are essential parts of the knee joint for weight bearing, stabilization, energy absorption, and joint lubrication. The capsule of the tibiofemoral joint is continuous with the capsule of the patellofemoral joint. The patellofemoral joint is comprised of the femoral trochlea in which the patella glides. The patella lies within the quadriceps tendon. The quadriceps tendon becomes the patellar tendon distal to the patella, which inserts onto the tibial tuberosity. Smooth hyaline cartilage covers the undersurface of the patella, which protects the patella during weight bearing. This is actually the thickest articular cartilage in the body. The iliotibial band (ITB) originates in the lateral hip region, crosses the knee joint, and attaches on the lateral tibia at Gerdy’s tubercle. The pes anserinus lies just medial to the tibial tuberosity and is the insertion site of the semitendinosus, sartorius, and gracilis tendons. There is a bursa located at this area known as the pes anserine bursa.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The knee is the most common site for injury in a runner. Studies have shown that the predominant site of lower extremity injury in runners is the knee, with the incidence ranging from 7.2% to 50%.1 Females have a greater incidence of lower extremity injuries compared to males.1 Greater training distance per week (more than 64 km/wk) is a risk factor for lower extremity injury in men, while an increase in training distance per week is a protective factor against knee injuries in both men and women.1 History of previous injuries is a risk factor for future injuries while running. High endurance strength in adolescence is a predictor of knee injury in men.2

NARROWING THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

History

A thorough history may give enough information for the diagnosis. Important questions to ask are if the athlete has had any changes in training surface, intensity of exercise, mileage, or footwear. Inquire if the athlete has had an injury in the knee before, how long they have had pain, what the pain inhibits them from doing, and if they have done any rehabilitation. Find out if they have any joint swelling, locking or giving out of the knee, any night pain, systemic symptoms, or pain in joints other than their knee.

The location of the pain can help focus the differential to particular conditions (see Fig. 18.9).

Anterior knee pain may be caused by patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS), patella subluxation, chondromalacia patellae, osteochondral defect, patellar tendinopathy, Osgood-Schlatter disease (OSD), Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome, prepatellar bursitis, quadriceps tendinopathy, fat pad syndrome, or degenerative joint disease (DJD). Lateral knee pain may be due to ITB friction syndrome, lateral meniscus tear, or lateral collateral ligament sprain. Medial knee pain may be secondary to plica, medial collateral ligament (MCL) sprain, medial mensical injury, or pes anserine bursitis. Posterior knee pain can be from popliteal cyst, hamstring strain, or posterior horn meniscal cyst.

Evidence-based Physical Exam

It is important to examine the asymptomatic knee so that a comparison can be made between the two. While examining the knee, keep in mind that knee pain can be referred from

other areas, such as the hip, particularly with young children. Description of specific knee exam maneuvers as related to overuse knee injuries is listed later in the chapter. Examination of acute injuries is reviewed in Chapter 18, Athlete with Acute Knee Injuries. Key point to remember is that the presence of an effusion in overuse knee pain strongly suggests intra-articular pathology including a degenerative meniscal tear, osteoarthritis (OA), osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), articular cartilage injury, or occult intra-articular fracture. Majority of overuse knee injuries, however, do not result in knee effusion as the structures are extra-articular (patella tendon, ITB) or are functional in nature (patellofemoral syndrome). Pain that radiates down the leg, dysthesias, or paresthesias is typically secondary to lumbar spine etiology. The following is a systematic approach to the knee exam with focus on overuse etiologies.

other areas, such as the hip, particularly with young children. Description of specific knee exam maneuvers as related to overuse knee injuries is listed later in the chapter. Examination of acute injuries is reviewed in Chapter 18, Athlete with Acute Knee Injuries. Key point to remember is that the presence of an effusion in overuse knee pain strongly suggests intra-articular pathology including a degenerative meniscal tear, osteoarthritis (OA), osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), articular cartilage injury, or occult intra-articular fracture. Majority of overuse knee injuries, however, do not result in knee effusion as the structures are extra-articular (patella tendon, ITB) or are functional in nature (patellofemoral syndrome). Pain that radiates down the leg, dysthesias, or paresthesias is typically secondary to lumbar spine etiology. The following is a systematic approach to the knee exam with focus on overuse etiologies.

Inspection

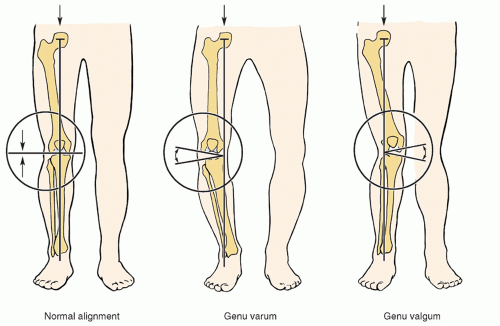

The exam can begin with observation of the patient standing. Focus should be on any evidence of genu valgum or varum (Fig. 19.1). Genu valgum can be associated with patellofemoral syndrome, while genu varum is most often associated with medial compartment knee OA. While standing, observe for any quadriceps atrophy by having the patient contract their quadriceps. Note the position of the patellae, whether they face in or out. Patellae that face in are a sign of femoral anteversion or increased medial femoral torsion and can be seen in patients with PFPS. The examiner should also observe the patient’s gait for signs of a painful or antalgic gait. Once supine, observe the knee for any swelling, erythema, or ecchymosis of the knee.

Palpation

After observing the knee, the examiner should palpate it for signs of an effusion, warmth, or tenderness. An effusion tends to signify an intra-articular injury such as anterior cruciate ligament, posterior cruciate ligament, or mensical injury, none of which are common in straightforward activities such as running.

Tenderness at the distal pole of the patella is found in patellar tendinopathy and also in Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome. Tenderness in the patellar tendon itself can also be found in patellar tendinopathy. OSD will exhibit tenderness and prominence at the tibial tuberosity. Palpate the medial and lateral patella facets by displacing the patella medially and laterally to feel the undersurface of the patella. Tenderness is seen in PFPS, chondromalacia, plica syndrome, and patella joint OA. Palpate for the pes anserinus, which is located medial and slightly distal to the tibial tubercle. Tenderness is seen in pes anserine tendonitis and bursitis. Moving lateral from the tibial tubercle, the insertion of the ITB can be felt at Gerdy’s tubercle. Palpate along the entire ITB. Tenderness may indicate ITB friction syndrome.

Palpate the medial and lateral joint lines with the knee flexed to 90 degrees. Athletes with mensical injuries will have tenderness along the joint line. Tenderness at the medial or lateral tibial plateau or along the distal femur could indicate a stress fracture.

Range of Motion

Normal range of motion is 0 to 140 degrees. It is common to be able to extend into 3 to 5 degrees of hyperextension. Loss of passive range of motion may be due to effusion, loose body, or mensical injury.

Strength

Having the patient perform a single leg squat is another method to look for quadriceps atrophy and weakness. Patients with PFPS tend to have quadriceps atrophy and weakness especially of the vastus medialis oblique.3

Special Tests

Examine the mobility of the patella. It should move about half of its width medially and laterally with the knee in extension. A tight ITB may cause the patella to track laterally. Assessment of the ligaments and menisci can be done via joint line palpation and McMurray’s test. Meniscal tears and their exam are fully reviewed in Chapter 18, Athlete with Acute Knee Injuries.

Special tests found to be helpful in the assessment of knee pain in the runner include the patella grind test, the patella apprehension test, Ober’s test, and Noble’s test. The sensitivity and specificity of these tests have not been documented in the literature.

The patellar grind test assesses for patellofemoral dysfunction. It is performed by pressing on the area just proximal to the upper pole of the patella and having the patient contract their quadriceps. If they have pain with this maneuver, it is a positive patella grind test.

The Ober’s test examines the flexibility of the ITB. The patient should lie on their side with the affected leg facing up. The lower hip and knee should be straight. Standing behind the patient, place one hand on the hip to stabilize it and the other hand on the patient’s knee of the upper leg. The hip of the upper leg is then passively abducted and extended to about 40 degrees while the knee is in a flexed position. Finally, lower the leg into adduction as far as gravity will allow. If the ITB is tight, the leg will remain abducted, or not fall below horizontal, which results in a positive Ober’s test.

The Noble’s test assesses for ITB friction syndrome. While the patient is in the supine position, flex the knee to 90 degrees. The examiner should place their thumb on the lateral femoral epicondyle and move the leg into extension. Pain with this maneuver (a positive Noble’s test) is caused by the ITB rolling over the lateral femoral epicondyle.

Diagnostic Testing

Laboratory

Laboratory work is usually not required when diagnosing the etiology of knee pain. If the patient has systemic or infectious symptoms, then there may be a need for appropriate serology or cultures. A knee effusion without history of trauma should raise suspicion for possible autoimmune or infectious etiology and prompt serologic evaluation including lyme titers in endemic regions.

Imaging

X-rays should be the initial study when attempting to diagnose knee pain. Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views should be obtained. AP weight bearing of the knees in 30 degrees of flexion (tunnel view) should be assessed for joint space narrowing if concerned about OA; this will also show evidence of an osteochondral defect if one is present. The lateral view should be obtained to evaluate for OSD. An axial view (also known as sunrise, skyline, or merchant view) will show the position of the patella in relation to the femur. It is common to see laterally displaced patellae in patients with patellofemoral syndrome.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), and bone scintigraphy may be needed if patient requires further evaluation. MRI is the preferred study for soft-tissue structures, while a CT can delineate bony structures including cortical defects not appreciated on plain radiographs. Due to the relatively high radiation exposure with CT, its use should be limited to cases where imaging results would significantly alter management. Bone scintigraphy (bone scans) may be utilized to rule out metabolically active bone lesions or bone stress injuries.

Other Testing

Other diagnostic testing is generally not required in the routine evaluation of overuse knee injuries.

APPROACH TO THE ATHLETE WITH PATELLOFEMORAL PAIN SYNDROME (RUNNER’S KNEE)

PFPS, also called “runner’s knee,” is the most common cause of overuse anterior knee pain in athletes, and studies have shown it to be the most common cause of knee pain in runners.4,5 PFPS is pain localized to the patellofemoral joint with unaffected articular cartilage. Among adolescents and young adults, patella disorders are the most common knee problems seen.6 Incidence has been reported to be as high as one in four in athletes. PFPS is typically an overuse injury, but can be a traumatic injury as well. PFPS affects 15% to 33% of adults and 21% to 45% of adolescents, being more common in female adolescents. The exact etiology of pain is unknown, but the syndrome is felt to be secondary to abnormal tracking of the patella in the femoral groove. Contact stresses on the patellofemoral joint are higher than any other weight-bearing joint. Predisposing factors have been suggested to be a lateral tracking patella,7 tight lateral retinaculum, tight

ITB, hip musculature weakness, abnormal vastus medialis oblique/vastus lateralis reflex timing, or an excessive Q angle (>20 degrees).8 PFPS should be differentiated from other causes of anterior knee pain including chondromalacia, patellar tendinopathy, and patellofemoral joint OA.

ITB, hip musculature weakness, abnormal vastus medialis oblique/vastus lateralis reflex timing, or an excessive Q angle (>20 degrees).8 PFPS should be differentiated from other causes of anterior knee pain including chondromalacia, patellar tendinopathy, and patellofemoral joint OA.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAM

Patients will complain of anterior knee pain, or pain behind the patella. They may isolate the pain to the medial or lateral aspect of the patella. When asked where the pain is, patients often draw a circle around the patella with their finger. Running, jumping, and walking up- and downstairs tend to exacerbate PFPS. They may also have pain after prolonged periods of sitting (theater sign), getting up from a chair, and squatting. The onset of pain is insidious and will often stop the athlete from participating in activity when severe.

On physical exam, conditions such as femoral anteversion and external tibial torsion should be noted as they may lead to patellofemoral joint pain. Increased patella mobility may play a role in PFPS.6 A tight ITB or lateral retinaculum may cause a lateral tracking patella and create pain. Palpate the medial and lateral patella facets for tenderness by medially and laterally deviating the patella and palpating its undersurface. Patella grind test will generally recreate patients’ pain with PFPS. Check the flexibility of the quadriceps and gastrocnemius muscles because decreased flexibility has been shown to be a risk factor for PFPS.6 A single leg squat performed by the patient enables the examiner to evaluate the quadriceps strength, in particular the vastus medialis oblique. Also, patients with PFPS tend to have pain with squats. Studies have shown that runners with higher knee abduction impulses are at increased risk for PFPS.9

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

For athletes with chronic knee pain or history of trauma, imaging helps to rule out more serious conditions. Radiographs, especially the sunrise or merchant view, of the knees may show lateral tracking of the patella. The presence of patella spurring indicates patellofemoral OA rather than PFPS. If symptoms persist, consider an MRI to look for osteochondral defects, chondromalacia, or occult intraarticular pathology.

TREATMENT

Nonoperative

Nonoperative treatment is the mainstay of therapy.

Activity modification involves limiting bending, kneeling, squatting, or excessive stairs.

Physical therapy (PT) to increase strength of quadriceps, especially the vastus medialis oblique, and the gluteus muscles.

One study showed that by strengthening hip flexors, stretching the ITB, and improving iliopsoas flexibility, patients were able to decrease their knee pain.10

A randomized placebo-controlled study found a 6-week, once weekly program significantly reduced PFPS symptoms compared with a sham PT program.11 The program consisted of quadriceps muscle retraining, patellofemoral joint mobilization, patellar taping, and daily home exercises.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) help alleviate the pain of PFPS on a short-term basis, but have not been proven to help in the long term.12

Operative

Surgery is rarely required and reserved for recalcitrant cases that have not responded to a prolonged course of conservative treatment.

The type of surgical procedure depends on the characteristics of patellar maltracking.

Patients with a tight lateral retinaculum associated with a rotational tilt of the patella may benefit from a lateral release surgery, usually done by arthroscopy. Side effect of the surgery is medial patellar subluxation.

Arthroscopic patellar debridement alone may be enough for some patients to decrease their pain.

Other surgeries are proximal realignment or distal realignment: both procedures are often done with anteromedialization of the tibial tubercle.13

One study of patients with chronic PFPS concluded that when arthroscopy was used in addition to a home exercise program, there was no better outcome compared to when a home exercise program was used alone.14

Prognosis/Return to Play

Patients generally have a good prognosis and respond well to conservative treatment.

Athletes may return to play on an as-tolerated basis as pain improves.

Complications/Indications for Referral

Prolonged symptoms, progressively worsening symptoms, or failure of conservative measures are indications for referral to a sports medicine physician. Consider surgery when the athlete has completed a thorough rehabilitation program for 6 to 12 months, yet pain persists. Indications for surgery include inability to perform activities of daily living. Complications are rare, but include patella dislocation if PFPS is associated

with patella instability. A large knee effusion or signs of infection are red flags warranting immediate attention.

with patella instability. A large knee effusion or signs of infection are red flags warranting immediate attention.

APPROACH TO THE ATHLETE WITH ILIOTIBIAL BAND FRICTION SYNDROME

ITB friction syndrome is an overuse injury and is the second most common overuse injury in runners.5,9 It is the most common running injury of the lateral knee and has an incidence of 1.6% to 12%.15 The ITB originates in the lateral hip region, crosses the knee joint, and attaches on the lateral tibia at Gerdy’s tubercle (Fig. 19.2).

Pain is caused by friction between the ITB and the lateral femoral epicondyle; friction is maximized when the knee is flexed to 30 degrees. Contact with the epicondyle occurs near foot strike, and in runners, the repetitive contact may cause inflammation of the ITB, which then leads to degenerative changes or bursitis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree