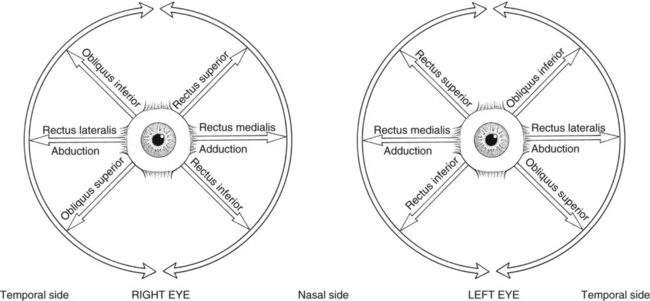

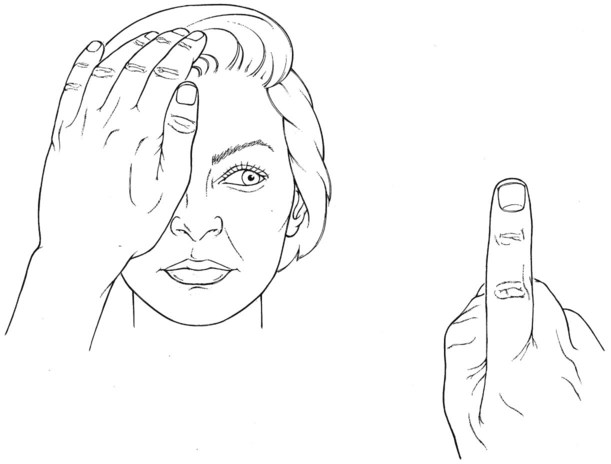

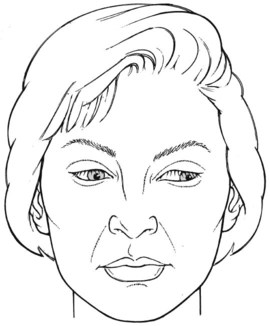

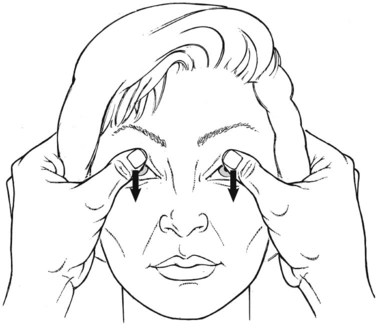

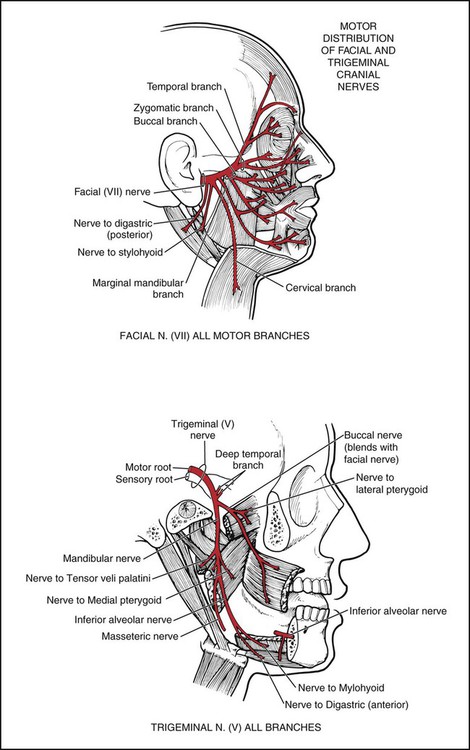

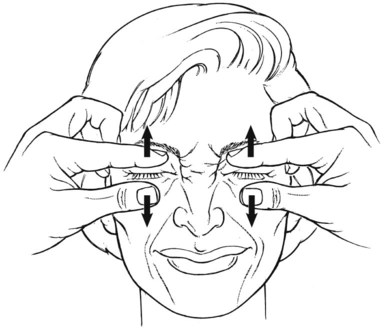

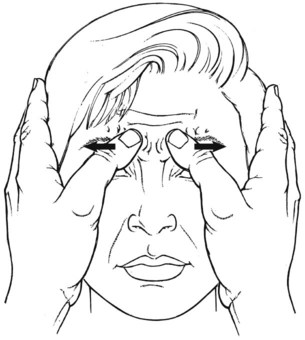

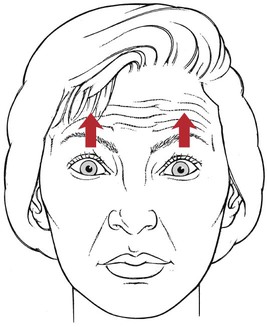

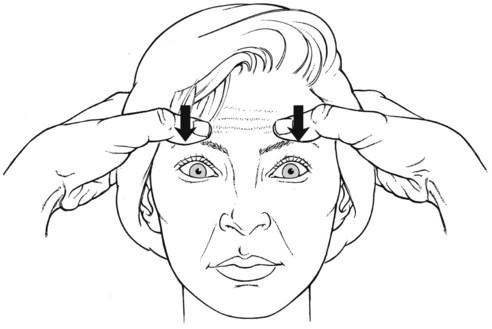

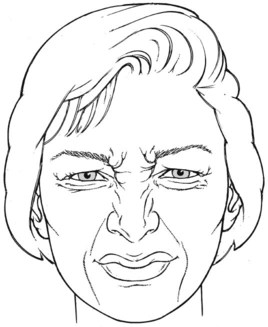

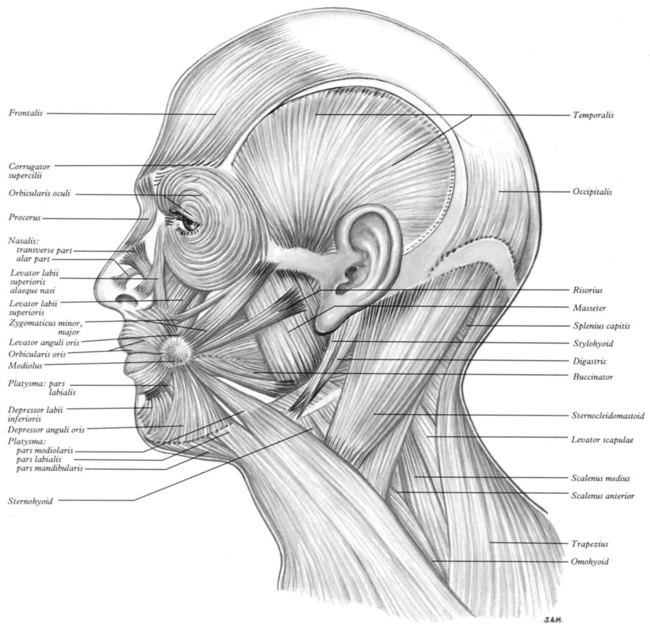

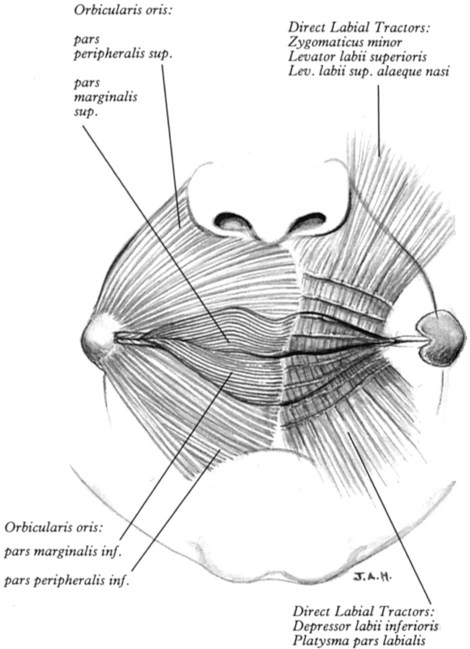

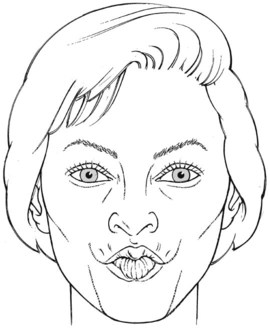

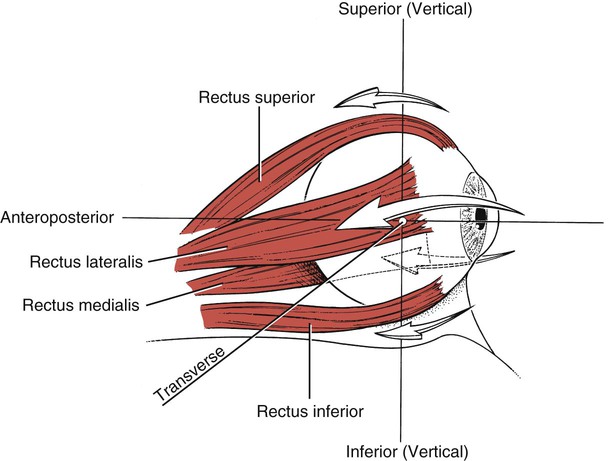

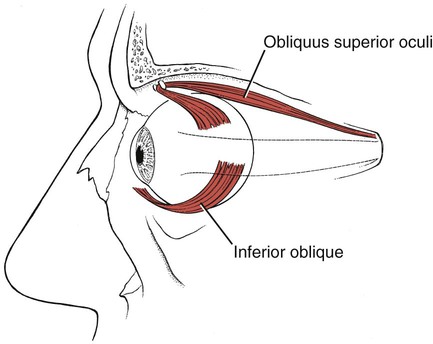

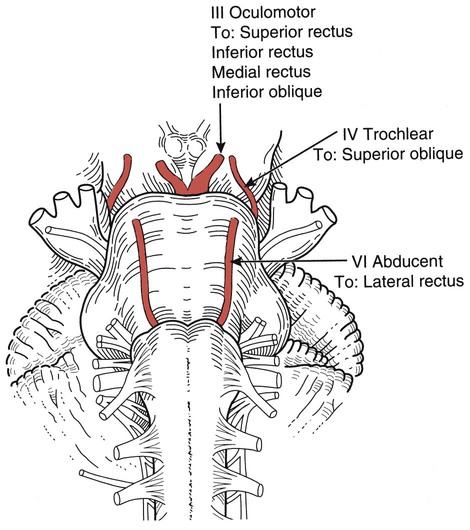

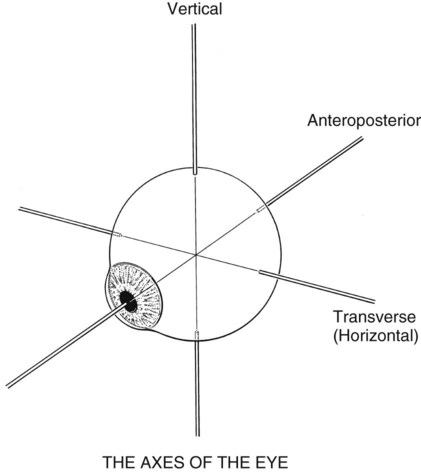

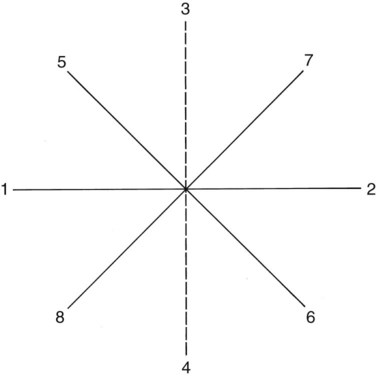

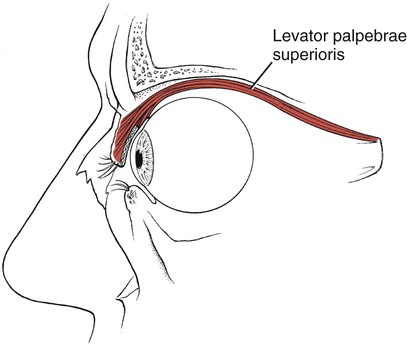

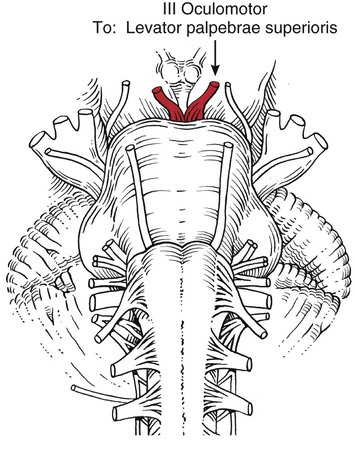

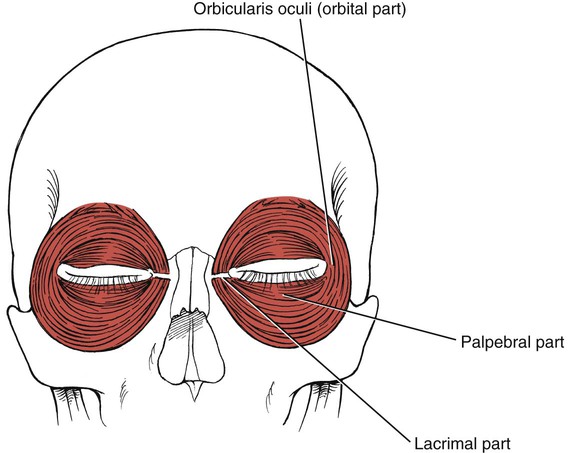

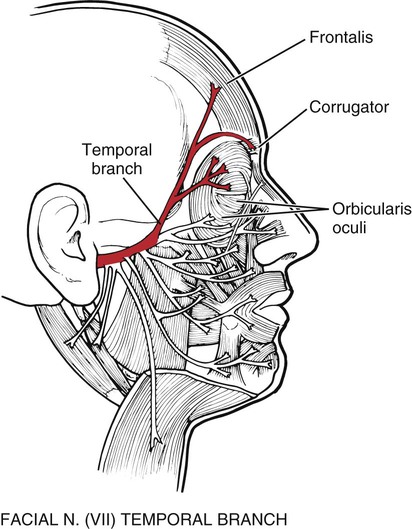

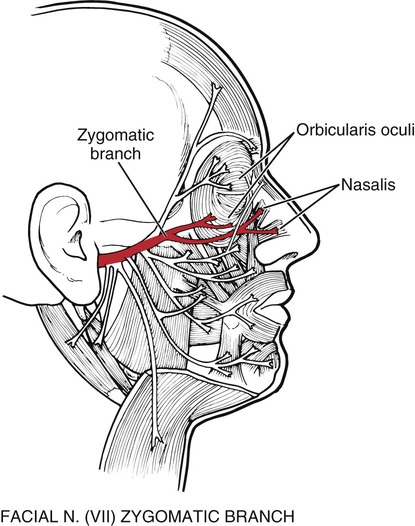

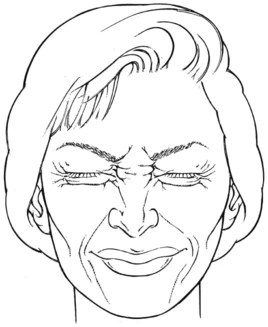

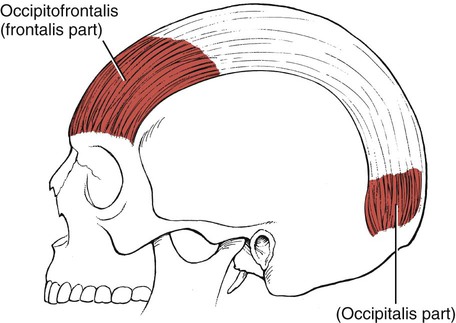

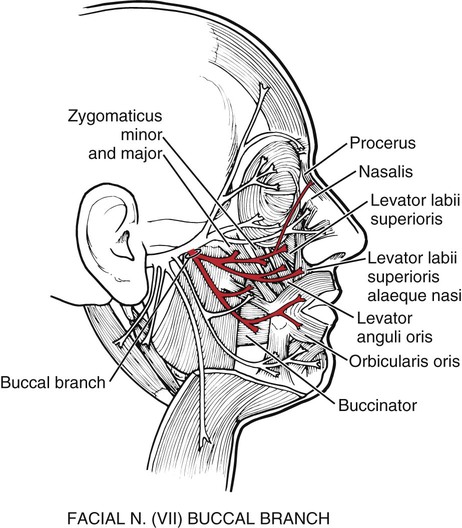

The six extraocular muscles of the eye (Figure 7-1 and Figure 7-2) move the eyeball in directions that depend on their attachments and on the influence of the movements themselves. It is usual that no muscle of the eye acts independently, and because these muscles cannot be observed, palpated, or tested individually, much of the knowledge of their function is derived from some variety of dysfunction. The extraocular muscles are innervated by cranial nerves III (oculomotor), IV (trochlear), and VI (abducent) (Figure 7-3). Table 7-1 The eyeball rotates in the orbital socket around one or more of three primary axes (Figure 7-4), which intersect in the center of the eyeball.1 Vertical axis: Around this axis the lateral motions (abduction and adduction) take place in a horizontal plane. Transverse axis: This is the axis of rotation for upward and downward motions. Anteroposterior axis: Motions of rotation in the frontal plane occur around this axis. The extraocular muscles seem to work as a continuum; as the length of one changes, the length and tension of the others are altered, giving rise to a wide repertoire of paired movements.2,3 Despite this continuous commonality of activity, the function of the individual muscles can be simplified and understood in a manner that does not detract from accuracy but simplifies the test procedure. Conventional clinical testing assigns the following motions to the various extraocular muscles (Figure 7-5).1–3 2. Rotation of the eyeball so the vertical axis is outward. 3. Note: In paralysis, the eyeball is deviated downward and somewhat laterally; it cannot move upward when in abduction. 4. Note: In a III nerve lesion, the eye is outward and cannot be brought in. This lesion also results in ptosis, or drooping, of the upper eyelid.2,3 Eye movements are tested by having the patient look in the cardinal directions (numbers in parentheses refer to tracks shown in Figure 7-6).2 All pairs in tracking are antagonists. Laterally (1) Upward and laterally (5) Medially (2) Upward and medially (7) Upward (3) Downward and medially (6) Downward (4) Downward and laterally (8) The range, speed, and smoothness of the motion should be observed, as well as the ability to sustain lateral and vertical gaze.2–4 The therapist will not be able to use these observational methods to distinguish movement deviations accurately because accuracy requires the sophisticated instrumentation used in ophthalmology. The tracking movements will appear normal or abnormal, but little else will be possible. Table 7-2 MUSCLES OF THE EYELIDS AND EYEBROWS The face should be observed for mobility of expression, and any asymmetry or inadequacy of muscles should be documented. A one-sided appearance when talking or smiling, a lack of tone (with or without atrophy), the presence of fasciculations, asymmetrical or frequent blinking, smoothness of the face, or excessive wrinkling are all clues to VII nerve involvement. Opening the eye by raising the upper eyelid is a function of the levator palpebrae superioris (see Figure 7-10). The muscle should be evaluated by having the patient open and close the eye with and without resistance. The function of this muscle is assessed by its strength in maintaining a fully opened eye against resistance. In the presence of a facial (VII) nerve lesion, the levator sign may be present.2 In this case, the patient is asked to look downward and then slowly close the eyes. A positive levator sign is noted when the upper eyelid on the weak side moves upward because the action of the levator palpebrae superioris is unopposed by the orbicularis oculi. The orbicularis oculi muscle is the sphincter of the eye (Figure 7-13).1 Its lids are innervated by the facial (VII) nerve (temporal branch and zygomatic branch) (Figures 7-14 and 7-15). Its palpebral portion closes the eyelids gently, as in blinking and sleep. The orbital portion of the muscle closes the eyes with greater force, as in winking. The lacrimal portion draws the eyelids laterally and compresses them against the sclera to receive tears. All portions act to close the eyes tightly (Figure 7-16). Observation of the patient without specific testing will detect weakness of the orbicularis because the blink will be delayed on the involved side. To examine the frontal belly of the occipitofrontalis muscle (Figure 7-21 and see Figure 7-14), the patient is asked to create an expression of surprise where the forehead skin wrinkles horizontally. The occipital belly of the muscle is not tested usually, but it draws the scalp backward. Table 7-3 *The depressor septi often is considered part of the dilator nares. The three muscles of the nose are all innervated by the facial (VII) nerve. The procerus (Figure 7-24) draws the medial angle of the eyebrows downward, causing transverse wrinkles across the bridge of the nose. The nasalis (compressor nares) depresses the cartilaginous portion of the nose and draws the ala down toward the septum (see Figure 7-15). The nasalis (dilator nares) dilates the nostrils. The depressor septi draws the alae downward, constricting the nostrils. Table 7-4 This circumoral muscle (Figures 7-28 and 7-29) serves many functions for the mouth. It closes the lips, protrudes the lips, and holds the lips tight against the teeth. Furthermore, it shapes the lips for such functional uses as kissing, whistling, sucking, drinking, and the infinite shaping for articulation in speech. (For innervation, see Figure 7-25.)

Assessment of Muscles Innervated by Cranial Nerves

Jacqueline Montgomery

Introduction to Testing and Grading

Extraocular Muscles

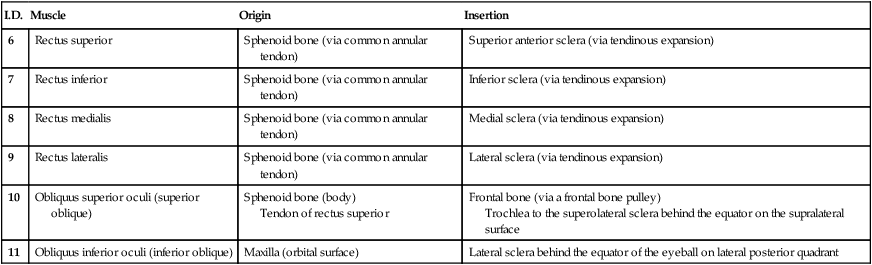

I.D.

Muscle

Origin

Insertion

6

Rectus superior

Sphenoid bone (via common annular tendon)

Superior anterior sclera (via tendinous expansion)

7

Rectus inferior

Sphenoid bone (via common annular tendon)

Inferior sclera (via tendinous expansion)

8

Rectus medialis

Sphenoid bone (via common annular tendon)

Medial sclera (via tendinous expansion)

9

Rectus lateralis

Sphenoid bone (via common annular tendon)

Lateral sclera (via tendinous expansion)

10

Obliquus superior oculi (superior oblique)

Sphenoid bone (body)

Tendon of rectus superior

Frontal bone (via a frontal bone pulley)

Trochlea to the superolateral sclera behind the equator on the supralateral surface

11

Obliquus inferior oculi (inferior oblique)

Maxilla (orbital surface)

Lateral sclera behind the equator of the eyeball on lateral posterior quadrant

The Axes of Eye Motion

Eye Motions

11 Obliquus inferior (III, Oculomotor)

Eye Tracking

Muscles of the Face and Eyelids

I.D.

Muscle

Origin

Insertion

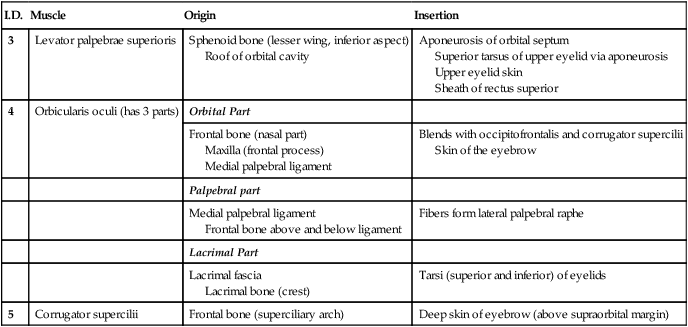

3

Levator palpebrae superioris

Sphenoid bone (lesser wing, inferior aspect)

Roof of orbital cavity

Aponeurosis of orbital septum

Superior tarsus of upper eyelid via aponeurosis

Upper eyelid skin

Sheath of rectus superior

4

Orbicularis oculi (has 3 parts)

Orbital Part

Frontal bone (nasal part)

Maxilla (frontal process)

Medial palpebral ligament

Blends with occipitofrontalis and corrugator supercilii

Skin of the eyebrow

Palpebral part

Medial palpebral ligament

Frontal bone above and below ligament

Fibers form lateral palpebral raphe

Lacrimal Part

Lacrimal fascia

Lacrimal bone (crest)

Tarsi (superior and inferior) of eyelids

5

Corrugator supercilii

Frontal bone (superciliary arch)

Deep skin of eyebrow (above supraorbital margin)

Eye Opening (3. Levator palpebrae superioris)

Closing the Eye (4. Orbicularis oculi)

Raising the Eyebrows (1. Occipitofrontalis, frontalis part)

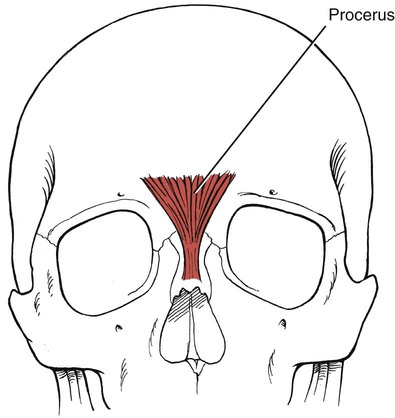

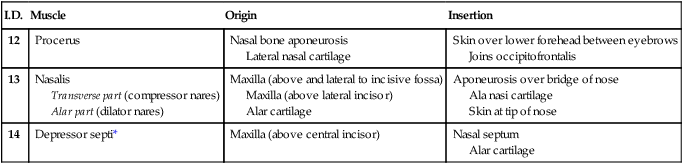

Nose Muscles

I.D.

Muscle

Origin

Insertion

12

Procerus

Nasal bone aponeurosis

Lateral nasal cartilage

Skin over lower forehead between eyebrows

Joins occipitofrontalis

13

Nasalis

Transverse part (compressor nares)

Alar part (dilator nares)

Maxilla (above and lateral to incisive fossa)

Maxilla (above lateral incisor)

Alar cartilage

Aponeurosis over bridge of nose

Ala nasi cartilage

Skin at tip of nose

14

Depressor septi*

Maxilla (above central incisor)

Nasal septum

Alar cartilage

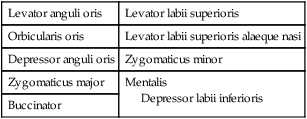

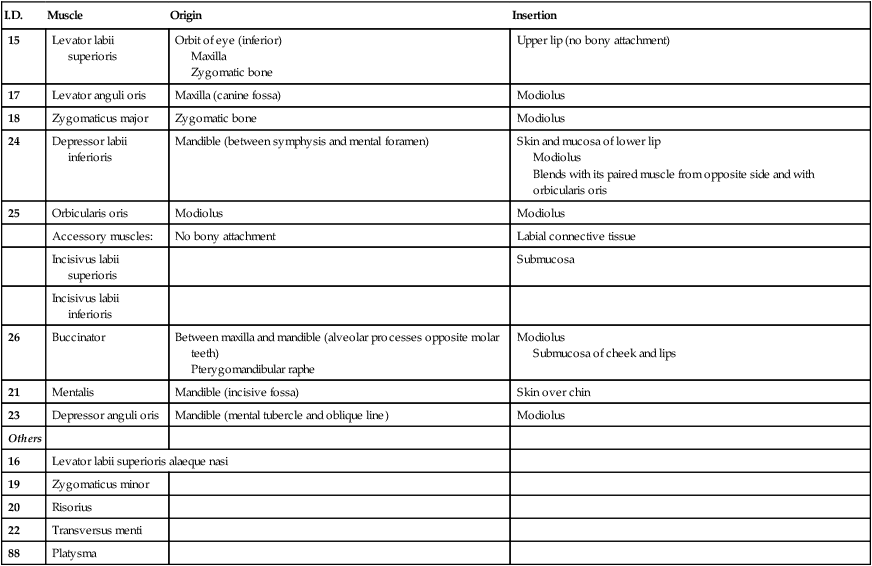

Muscles of the Mouth and Face

I.D.

Muscle

Origin

Insertion

15

Levator labii superioris

Orbit of eye (inferior)

Maxilla

Zygomatic bone

Upper lip (no bony attachment)

17

Levator anguli oris

Maxilla (canine fossa)

Modiolus

18

Zygomaticus major

Zygomatic bone

Modiolus

24

Depressor labii inferioris

Mandible (between symphysis and mental foramen)

Skin and mucosa of lower lip

Modiolus

Blends with its paired muscle from opposite side and with orbicularis oris

25

Orbicularis oris

Modiolus

Modiolus

Accessory muscles:

No bony attachment

Labial connective tissue

Incisivus labii superioris

Submucosa

Incisivus labii inferioris

26

Buccinator

Between maxilla and mandible (alveolar processes opposite molar teeth)

Pterygomandibular raphe

Modiolus

Submucosa of cheek and lips

21

Mentalis

Mandible (incisive fossa)

Skin over chin

23

Depressor anguli oris

Mandible (mental tubercle and oblique line)

Modiolus

Others

16

Levator labii superioris alaeque nasi

19

Zygomaticus minor

20

Risorius

22

Transversus menti

88

Platysma

Lip Closing (25. Orbicularis oris)