CHAPTER 1 Assessment

Introduction

Why undertake a primary patient assessment?

Information from the assessment helps the practitioner to:

• arrive at a differential diagnosis or definitive diagnosis

• identify the likely cause of the problem (aetiology), e.g. trauma, pathogenic microorganism

• identify any factors that may influence the choice of treatment, e.g. poor blood supply, current drug regimen

• assess the extent of pathological changes so that a prognosis can be made

• establish a baseline in order to identify whether the condition is deteriorating or improving

• determine the need for further investigations (e.g. X-rays)

The assessment process

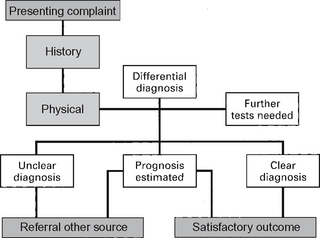

Assessment comprises three elements: the interview, observation and tests (Table 1.1). Information from the interview and observation is used to formulate ideas about the likely diagnosis and cause. Further information may be sought via the interview and the use of clinical and specialist tests or investigations. The practitioner uses the data gained from the assessment to formulate a hypothesis(es) from which a diagnosis will be reached. This diagnosis will be used to inform the management plan (Fig. 1.1). Where possible, the cause (aetiology) of the problem should be identified, as part of the management plan would be to eradicate or reduce the effects of the cause.

Table 1.1 Components of an assessment

| Component | |

|---|---|

| Assessment interview | |

| Observation and clinical examination | |

| Laboratory and hospital tests | |

To make a good assessment, a practitioner requires good interviewing (communication) and observational skills. It is also essential that the practitioner has effective listening skills and knows when and which questions to ask the patient (see Ch. 2). Research has shown that most diagnoses are based on observation and information volunteered by the patient (Lee et al 2006, Sandler 1979). For patients with complex pathology, it may not be appropriate to follow normal models of diagnostic practice as many conditions will not present in a typical ‘textbook’ fashion. This has led to the development of subspecialty models of clinical assessment such as the ‘permeable brick wall’ theory for neuromuscular assessment developed by Maitland et al (2001). This theory recommends that the clinician should treat a patient’s presenting symptoms rather than follow a treatment programme based on an exact diagnosis, as this may not be possible because of the variable and mixed nature of neurological symptoms and conditions.

Risk assessment

Risk assessment serves two purposes:

On account of the demands on time it is often necessary for the practitioner to differentiate between those patients who need immediate attention and those who do not. Table 1.2 summarises the presenting problems which should be given high priority. In clinics where there are lengthy waiting lists, patients may be screened initially to assess whether they have one or more of the problems listed in Table 1.2 and are then given immediate treatment.

Table 1.2 Presenting problems which should be given high priority

| Problem | Features |

|---|---|

| Pain | |

| Infection | |

| Ulceration | |

| Acute swelling | |

| Abnormal skin changes |

The term ‘at risk’ usually denotes those patients at risk of developing ulceration and infection. Identifying those ‘at risk’ is a complex task. Currently, there is sparse research into risk factors related to lower limb problems, and thus it is difficult to produce risk-assessment methods that are robust and valid. Considerable research has been undertaken into the risk assessment of pressure ulcers (Lothian 1987, Sharp & McLaws 2006). In relation to the lower limb some work has been undertaken into developing methods of risk assessment to identify patients with diabetes who are at risk of developing foot ulcers (Zahra 1998, Boyko et al 2006). Risk assessment has also been applied to numerous other health problems such as falls in the older population (DeMott et al 2007), muscle flexibility and muscle injury (Witvrouw et al 2003), and deep vein thrombosis (McCaffrey et al 2007).

Making a diagnosis

Hypothetico-deductive reasoning is based on generating hypotheses using clinical data and knowledge. These hypotheses are tested through further inquiry during the assessment. The evidence gained is evaluated in relation to existing knowledge and a conclusion reached on the basis of probability (Buckingham & Adams 2000, Gale 1982).

The interpretative model is different from the other two models. This approach is based on the practitioner gaining a deep understanding of the patient’s perspective and the influence of contextual factors. Protagonists of this approach believe that the meaning patients give to their problems, including their understanding of and their feelings about their problem, can significantly influence their levels of pain tolerance, disability and the eventual outcome (Ferurestein & Beattie 1995).

Studies have shown that with all these approaches there is an association between clinical reasoning and knowledge (De Bruin et al 2005, Higgs & Jones 2000). There is a symbiotic relationship between the knowledge base of practitioners and their clinical reasoning ability. It is not possible to develop problem-solving skills in the absence of cognitive knowledge related to the specific problem. The ability to diagnose a condition improves when the knowledge of basic science is combined with clinical knowledge (De Bruin et al 2005).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree