CHAPTER 17 The painful foot

Introduction

Pain is a subjective phenomenon – ‘Pain is whatever the experiencing person says it is, existing whenever the experiencing person says it does’ (McCaffery & Beeke 1989). We can assess pain in a variety of ways and it is essential for the practitioner to be aware of these assessment strategies when assessing foot pain (see Ch. 4). Assessment of the presenting complaint of the patient is covered in detail in Chapter 3.

There are many ways in which we can classify the pathologies that cause pain within the foot:

How common is foot pain?

Pain in the foot is a common complaint. Garrow et al (2004) in a survey of almost 5000 people found that 9.5% had disabling foot pain. Some studies have shown higher incidences: 14% in adolescents (Spahn et al 2004), rising to 36% in older patients (Menz et al 2006b). The incidence of foot pain increases with particular foot deformities or pathologies. Ribu et al (2006) found that 75% of patients with diabetic foot ulcers had foot pain from these ulcers, which may come as a surprise to many practitioners who believe that neuropathic ulcers are always painless.

Foot deformity is thought to be a common cause of foot pain. The evidence from the literature to support this hypothesis is variable. With certain deformities there is a strong correlation, such as pes cavus. A recent study found that 60% of subjects with this structural deformity had foot pain (Burns et al 2005). Hallux valgus and lesser toe deformities were not found to be a significant cause of foot pain in an elderly population (Badlissi et al 2005) but this is in contrast to the work of Benvenuti et al (1995) who found a significant relationship between pain and these and other foot pathologies such as plantar calluses and pes planus in a similarly aged population.

When considering foot deformity and its association with pain, one issue is the degree of deformity. It would be natural to assume that the bigger the deformity the more pain the patient would experience. However, this is not the case and has been demonstrated with several foot deformities, most recently hallux valgus. Thordarson et al (2005) found that the degree of pain experienced by patients waiting for hallux valgus surgery had no correlation with the degree of deformity measured clinically or radiologically. Such evidence reinforces the subjective nature of pain. However, this does not mean that foot deformity is not a major cause of morbidity. Even in those with foot deformity and no foot pain there is still the potential for significant other pathology and morbidity. Foot deformity, especially lesser toe deformities and hallux valgus, has been shown to increase the risk of falls in the elderly (Menz et al 2006a). Pes planus has been shown to increase the incidence of osteoarthritis in the knee and pes cavus has been shown to increase the incidence of osteoarthritis of the hip (Reilly et al 2006). Foot deformity is a known risk factor for foot ulceration in patients with diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis.

Examination of the patient with foot pain

![]() You should first observe the patient, not the foot. It is useful to highlight those traits that have been discussed under medical history (Ch. 5) as the source of pain may be explained by general disease processes. Assess the patient’s attitude. This may reveal psychological variations from normal and may influence your assessment strategy and the outcome of any treatment. Pointers concerning general health include the following:

You should first observe the patient, not the foot. It is useful to highlight those traits that have been discussed under medical history (Ch. 5) as the source of pain may be explained by general disease processes. Assess the patient’s attitude. This may reveal psychological variations from normal and may influence your assessment strategy and the outcome of any treatment. Pointers concerning general health include the following:

• Is the patient well nourished (obese or thin and wasted)?

• Colour (pale and anaemic, jaundiced)?

• Look at the hands, are they misshapen (rheumatoid arthritis)?

Examination of the foot begins with watching the patient walk (see Ch. 10). An antalgic limp, where the patient will spend only a short period of time on the painful foot, is a clear positive sign. The limp may be linked with other problems associated with proximal joints or the back; these should be excluded. Look at shoe wear on the sole; this may indicate an abnormal gait pattern. Are the toes severely clawed, possibly suggesting a neurological problem? It is important to note any callosities, both dorsally and on the sole, as these indicate areas of high pressure and friction. Similarly, one must remember all the structures running under any area of tenderness.

The sources of pain are numerous and can be subdivided for convenience into problems affecting different tissues, different regions of the foot, generalised disorders and referred pain. Table 17.1 provides an overview of pathologies by tissue type which may cause foot pain. Tables 17.2–17.4 cover the common, less common and conditions not to be missed that can be the source of pain in the forefoot, midfoot and rearfoot respectively. In many cases the origins are not clear and assessment and further investigations are necessary to isolate the cause. The practitioner must always remember that multiple conditions may co-exist either in isolation or by association through compensation, for example a patient with a painful bunion may develop a Morton’s neuroma through transfer metatarsalgia. It is important to identify these potential causal links as they can assist in the diagnosis and subsequent management of multiple conditions.

Table 17.1 Causes of foot pain by anatomical structure

| Tissue type | Condition |

|---|---|

| Osseous | Fracture, accessory bones, bone tumour, metabolic bone disease, exostoses, traction apophysitis |

| Articular | Osteoarthritis, inflammatory arthritis, osteochondral defect, osteochondritis desiccans, tarsal coalition |

| Ligament | Sprain/tear/rupture |

| Muscle/tendon | Tear or rupture, tendinopathy, subluxing tendons, tibialis posterior dysfunction |

| Fascia | Plantar fasciitis, compartment syndrome, tumour, e.g. plantar fibroma |

| Nerves | Entrapments, peripheral neuropathy, referred pain (radiculopathy) |

| Skin/subcutaneous | Bursitis, soft tissue masses and tumours |

| Vascular | Peripheral vascular disease, vasculitis, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), venous insufficiency |

| All tissue types | Infection, complex regional pain syndrome |

Table 17.2 Conditions that can cause forefoot pain

| Common | Less common | Not to be missed |

|---|---|---|

| Corns/calluses | Plantar wart | Fractured sesamoid |

| Onychocryptosis/onychauxis | Subungual exostosis | Stress fracture (usually metatarsal) |

| Hallux valgus | Transverse plane deformity lesser MTPJ | Complex regional pain syndrome |

| Hallux rigidus | IPJ or lesser MTPJ arthritis | Charcot neuroarthropathy |

| Lesser toe deformity-Hammer/claw toe | Lesser toe deformity – cross-over toe, clinodactyly, adductovarus toe | Glomus tumour |

| Morton’s neuroma | Joplin’s neuroma | Malignant melanoma |

| Inflammatory arthritis, e.g. Rh. A | Bursitis (usually MTPJ) | |

| Lesser MTPJ capsulitis (especially 2nd) | Sesamoiditis | |

| Gout |

MPTJ, metatarsophalangeal joint; IPJ, interphalangeal joint.

Table 17.3 Conditions that can cause midfoot pain

| Common | Less common | Not to be missed |

|---|---|---|

| Instep plantar fasciitis | Extensor/tibialis anterior tendinopathy | Lisfranc dislocation |

| Plantar fibroma | Köhler’s disease | Complex regional pain syndrome |

| Osteoarthritis 2nd/3rd TMT joints | Stress fracture – metatarsal base, navicular | Malignant melanoma |

| Soft tissue mass, e.g. ganglion | Lisfranc injury | |

| Charcot’s neuroarthropathy | Osteoarthritis 1st TMT/intercuneiform/navicular-cuneiform joints | |

| Nerve entrapment (deep peroneal) | Nerve entrapment (superficial peroneal) Peripheral vascular disease, e.g. rest pain Gout |

TMT, tarsometatarsal.

Table 17.4 Conditions that can cause rearfoot pain

| Common | Less common | Not to be missed |

|---|---|---|

| Plantar fasciitis | Plantar wart | Tarsal coalition |

| Nerve entrapment (lateral plantar nerve) | Tarsal tunnel syndrome | Bone tumour, e.g. osteoid osteoma |

| Tibialis posterior dysfunction | Peroneal tendinopathy/subluxing tendons | Complex regional pain syndrome |

| Haglund’s or retrocalcaneal exostosis | Accessory bone (os tibialis externum, os trigonum) | Charcot neuroarthropathy |

| Achilles tendinopathy | Osteochondral defect talus | Inflammatory arthropathies, e.g. ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter’s disease |

| Osteoarthritis, subtalar joint | Osteoarthritis talonavicular joint | Fracture (traumatic or stress calcaneus or talus) |

| Sinus tarsi syndrome | Spring ligament injury | Malignant melanoma |

| Sever’s disease |

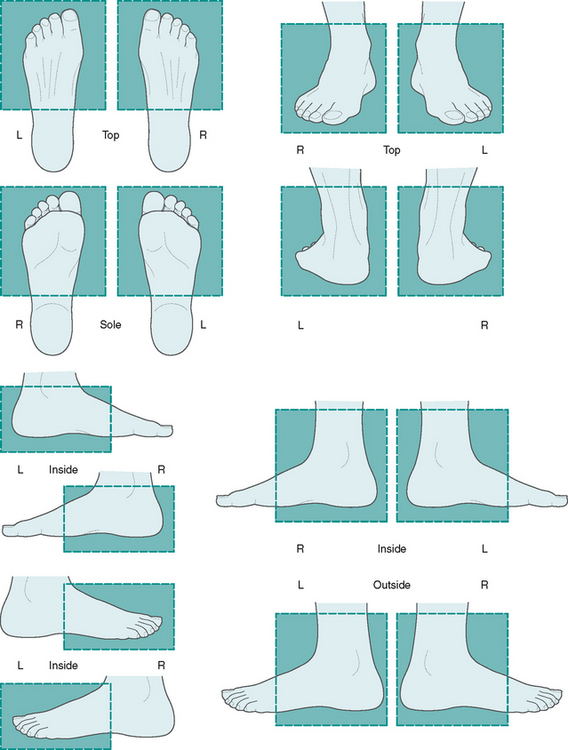

It is important to localise the current pain/symptoms to specific anatomical structures. Manikin diagrams or photographic pain maps (Fig. 17.1) are helpful in documenting this more quickly than is possible in words and provide a useful reference for future when the character or site of the pain changes over the course of treatment. The description of current pain/symptoms should be supplemented by an attempt to identify the precise structures affected and to reproduce the symptoms if appropriate either by direct palpation or by movement of the affected parts. The character of the symptoms (numbness, fatigue, pain), and, as appropriate, the pain characteristics (e.g. burning, bruised, achy) should be explored. Any influencing factors, for instance the effect of weightbearing/non-weightbearing activity, diurnal variation, footwear types will also help to identify whether local mechanical factors might be driving the pathology. Previous treatments should be explored in detail, both as a pointer to the disease process and to avoid duplicating mistakes or ineffectual treatments.

Having prompted the patient to describe the symptoms themselves it is appropriate also to gauge the impact of the symptoms on the patient and their daily life. This can be done in several ways the most common being to use visual analogue scales to quantify simply pain or other aspects of impairment. It has long been common practice to record this sort of information empirically but more recently there has been a burgeoning of approaches designed to explore this in a more structured way and to quantify the degree of impact. These are the so-called patient reported measures of health status or health-related quality of life. A variety of measures are available such as Garrow’s Manchester Foot Pain and Disability Questionnaire (MFPDQ) (Garrow et al 2000) and Bennett’s Foot Health Status Questionnaire (Bennett et al 1998, Bennett & Patterson 1998) (see Ch. 4). Patient-reported measures can be generally applied to all foot problems such as the two above or may be specific to diseases (such as the Leeds Foot Impact Scale for rheumatoid arthritis (RA)) (Helliwell et al 2005). The advantage of documenting the impact of symptoms formally is that it establishes a baseline against which the success of future treatment can be gauged and it also acts as a comparator with other groups.

Causes of pain in the foot

Articular conditions

Osteoarthritis

Aetiology

Other causes of OA in the foot and ankle include the following:

• Infection in the joint. Septic arthritis, unless diagnosed and treated early, will lead to lysis of cartilage and secondary OA.

• Inflammatory arthropathies such as RA and the seronegative arthritides, e.g. psoriatic arthritis, Reiter’s disease and ankylosing spondylitis. When the joint has been destroyed by the inflammatory process OA will ensue.

• Metabolic disorders such as gout and pseudogout.

• Systemic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, which can lead to Charcot’s foot or ankle. Limited joint mobility due to glycosylation of the soft tissues in patients with diabetes can also predispose to arthritic change of the affected joints.

• Proximal malalignment, e.g. following a malunited fractured tibia, has frequently been stated to lead to arthritis by imposing abnormal stresses on distal joints.

• Other miscellaneous conditions such as haemophilia or avascular necrosis (e.g. Freiberg’s disease affecting the second metatarsal head).

Clinical features

Generally these will be pain and stiffness in the area of the affected joint. Symptoms may start as aching after exercise and progress to pain after walking a distance. With time and progression of the arthritis the distance the patient can walk without pain gradually reduces. Pain may become constant and also present at night, disturbing sleep. How much pain the patient is experiencing is important to know but it is the impairment of function which probably influences us most when it comes to determining treatment. While one must be aware of the stoics who push themselves on regardless of the pain (and vice versa), how much a patient can do is often a good indicator of how severe the symptoms are. Stiffness may initially occur after the joint has been rested for a while, but with time the range of movement in the affected joint will decrease. Dorsiflexion is usually the first movement to be lost, and shoes with a slight heel raise may therefore be more comfortable. In severe OA the joint may completely lose movement and become virtually ankylosed. Patients may also complain of a limp, swelling or joint deformity.

Investigations

Plain X-rays, generally standing anteroposterior (AP for ankle, DP (dorsiplantar) for foot) and lateral, are essential (Ch. 12). The cardinal signs of OA are reduced joint space, sclerosis, cysts and osteophytes. Standing films are helpful as they may demonstrate deformity under load and the true loss of joint space due to cartilage erosion. Special views may be helpful to show particular structures more clearly such as Anthonsen’s view, which shows the medial and posterior subtalar facets. If infection is suspected then any open wounds can be swabbed. Aspiration of the joint for bacterial cultures may be helpful. Results from blood tests will be normal and are unhelpful unless the OA is secondary to a systemic disease, infection or metabolic cause such as gout (Ch. 13). Further to the discussion on pain it should be noted that the degree of X-ray change does not always correlate in a linear fashion with the patient’s symptoms or disability. It is always important to treat the patient and not the X-ray.

Osteochondroses

Osteochondral defects

A common articular injury is an osteochondral lesion or defect. These can be seen in any joint following a traumatic injury but are most often seen on the posteromedial or anterolateral aspects of the trochlear surface of the talus following an ankle sprain (Fig. 17.2). Other common sites include the first metatarsal head and the tibial plafond. Osteochondral lesions can be graded from I to IV (Table 17.5) and this helps dictate management. Classical symptoms are constant articular pain and stiffness with some swelling. Catching or locking can occur with grade III or IV lesions. Some residual pain and stiffness is often present and the patient should be counselled that early arthritis is likely to develop in the joint. Acute symptoms will be those of a sprained ankle, with the patient complaining of pain, swelling and difficulty walking. Chronic symptoms are more general, with patients complaining of discomfort, pain and perhaps stiffness during or after exercise. If an osteochondral fragment has become detached from the talar dome, then there may be locking and giving way in the ankle, suggestive of a loose body:

• Investigations (see Table 17.5)

Table 17.5 Classification of osteochondral lesions

| Grade of lesion | Description | Imaging investigation required for diagnosis |

|---|---|---|

| I | Subchondral cystic lesion with intact roof (also known as articular bone bruise) | Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) |

| II | Subchondral cystic lesion with communication to joint surface | Computed tomography (CT)/MRI (may be visible on X-ray) |

| III | Separate non-displaced chondral lesion | CT/MRI/X-ray |

| IV | Displaced chondral lesion | CT/MRI/X-ray |

Plain X-rays should initially be requested but in the acute stage X-rays may appear normal, especially if the lesion is stage I, i.e. only the articular cartilage is damaged (Berndt & Harty 1959). Even in a chronic lesion it may be difficult to detect any changes on plain X-ray. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the most sensitive, as well as the most expensive way of demonstrating the osteochondral fractures. Blood tests are of no value in the investigation of this condition.

Köhler’s or Mueller–Weiss syndrome

The paediatric form of this condition is most commonly seen in boys (6 : 1 male to female ratio) aged between 3 and 9 years. It is characterised by localised pain and swelling around the dorsal aspect of the navicular with warmth. The child often limps. In the adult form, the condition is usually more chronic in presentation with similar localisation of the pain and swelling but often with crepitus of the talonavicular joint and the development of a flatfoot posture. X-rays are used to confirm the presence of either form.

Tarsal coalition

This is a congenital condition, inherited as an autosomal dominant trait, in which adjacent tarsal bones have a fibrous, cartilaginous or bone connection or bridge which progressively restricts normal movement. This may be termed syndesmosis, synchondrosis or synostosis, respectively, and occurs in less than 1% of the population (Lemley et al 2006). Generally, it begins as a fibrous union in infancy and progresses to cartilaginous and then bony union; however, it may remain fibrous. The most common coalition is the talocalcaneal, followed by calcaneonavicular (Lemley et al 2006), and these account for 95% of all coalitions. Although rare, most other possible combinations have been described.

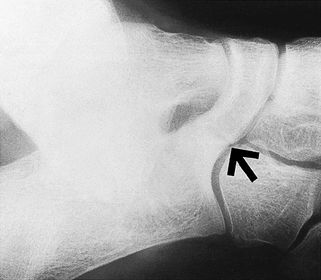

Appropriate plain X-rays may demonstrate a coalition; DP, lateral and medial oblique films should be taken. Medial oblique views show the calcaneonavicular coalition (Fig. 17.3). A Harris axial view may show a talocalcaneal coalition. Dorsal beaking on the head of the talus is a secondary change to abnormal movement, also suggesting this type of pathology (Case history 17.1). A long anterior calcaneal process may indicate a calcaneonavicular coalition on the lateral view. If X-rays are not diagnostic, a CT scan or MRI are the imaging modalities of choice to confirm the diagnosis.

Rheumatoid arthritis

RA is a systemic, inflammatory joint disease with an overall prevalence of about 0.8%. It is twice as common in females and usually presents in the fifth decade of life. The disease can lead to disabling pain with significant functional limitation associated with severe joint destruction and deformity. However, the course and severity of the disease varies widely and is often difficult to predict. The foot is affected in 90% of cases.

The diagnosis of RA is a clinical one based on observation of factors over a 6-week period (Table 17.6). The disease usually presents with morning stiffness, pain and swelling of the small joints of the hands and feet. It is estimated that RA first presents in the feet in 20% of cases. This is a key feature for podiatrists and other healthcare practitioners interested in the foot as many patients presenting with foot pain may have undiagnosed RA. This has led to the development of an early referral algorithm for RA (Emery et al 2002) which recommends immediate referral in the presence of:

Table 17.6 Components of an assessment

| Component Assessment interview | Presenting problem |

|---|---|

| Observation and clinical examination | |

| Laboratory and hospital tests |

Hallux valgus is present in up to 60% of established rheumatoid cases. The bunion deformity often pushes the lesser toes into either a hammered position, or more commonly causes lateral or ‘fibula deviation’ of the toes in the transverse plane. Another common presenting symptom may be pain localised to two of the lesser toes associated with splaying of the digits termed Jacobs’ daylight sign (Fig. 17.4). This is due to MTPJ synovitis in association with an intermetatarsal bursitis or other space-occupying mass such as a rheumatoid nodule. The localised inflammation often leads to neuroma symptoms due to irritation of the digital nerve and this may be the presenting complaint (see Case history 17.2).

17.2 Case history

A 35-year-old woman was referred by her physiotherapist and podiatrist due to pain and swelling in her left forefoot and right ankle. The ankle pain had been present for a year following a mild ankle sprain and the left forefoot pain had been present for the past 6 months. On examination there was discomfort with ankle range of movement but no mechanical or functional instability. There was pain in the left forefoot with the squeeze test and compression of the second/third MTPJs and second intermetatarsal space. There was splaying between toes 2 and 3 (Fig 17.4).

Psoriatic arthritis

Oligoarticular (several joints) or monoarticular (single joint) arthritis is the classical presentation of this condition. The pattern of involvement usually affects the interphalangeal joints in an asymmetric manner. A chronically swollen toe or finger is a common feature (Fig. 17.5). This is called dactylitis or sausage toe. Contrary to historical teaching, the foot and ankle is the most common site for PA (Hammerschlag et al 1991). The patient usually presents with painful joint(s) in the forefoot often with heel pain due to enthesopathy and tendon involvement such as tibialis posterior tendinopathy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree