CHAPTER 39 Arthroscopy in the Throwing Athlete

INTRODUCTION

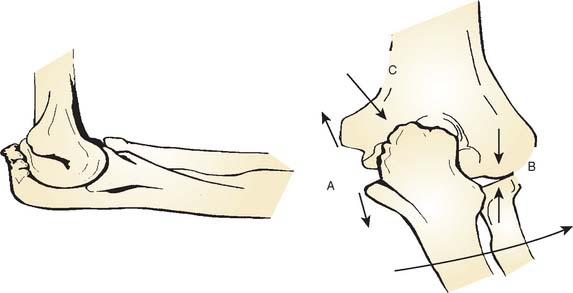

On the medial side, the repetitive tensile forces challenge the ultimate strength of the UCL, creating the well known injury risk to the ligament. Patients who develop valgus instability and continue to throw may initiate and exacerbate pathology in the posterior and lateral aspects of the elbow. In the posterior compartment, throwing repeatedly drives the olecranon into the olecranon fossa. The combination of valgus and extension forces creates shear forces on the medial aspect of the olecranon tip and olecranon fossa may cause injury and development of osteophytes (Fig. 39-1). This constellation of injuries has earned the term “valgus extension overload syndrome.” The relationship between the posterior compartment of the elbow and the UCL is evident in a series of professional baseball players who underwent olecranon débridement. Twenty-five percent of these athletes developed valgus instability and eventually required UCL reconstruction. This observation suggests that both the olecranon and the UCL contribute to valgus stability, and the authors believed that they may have missed UCL injuries in many of these patients. A cadaver study supports this theory and has demonstrated that UCL injury results in contact pressure alterations in the posterior compartment that explains the formation of osteophytes on the posteromedial olecranon.1 Another cadaver biomechanical study demonstrated that sequential partial resection of the posteromedial aspect of the olecranon increases elbow valgus angulation.14 Another cadaver study confirmed that strain in the UCL is increased with increasing posteromedial olecranon resection beyond 3 mm.15 These last two studies conclude that overaggressive olecranon resection used to treat posteromedial impingement puts the UCL at risk for injury. In summary, patients with posteromedial impingement pain from valgus extension overload should be critically evaluated for suspected concomitant UCL injuries and avoid overaggressive olecranon resection.

VALGUS EXTENSION OVERLOAD

Patients report posteromedial elbow pain that occurs during the deceleration phase of throwing as the elbow reaches terminal extension. Patients also report limited extension, which results from impinging posterior osteophytes or locking and catching resulting from loose bodies. Physical examination demonstrates crepitus and tenderness over the posteromedial olecranon, and pain is reproduced when forcing the elbow into extension. Valgus stress testing, milking maneuver, and moving valgus stress tests are important to assess the status of the UCL. Anteroposterior, lateral, oblique, and axillary views of the elbow may reveal posteromedial olecranon osteophytes and/or loose bodies (Fig. 39-2). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can further assess osteophytes and soft tissues (Fig. 39-3). Computed tomography with two-dimensional reconstruction and three-dimensional surface rendering may best visualize the bony pathology in addition to MRI.

Surgical treatment is indicated for those patients who maintain symptoms of posteromedial impingement despite nonoperative management. A relative contraindication to performing isolated olecranon débridement is the presence of UCL insufficiency. UCL insufficiency may become symptomatic following posteromedial decompression. Therefore, careful history, physical examination, and advanced imaging must be performed to avoid missed UCL injuries or valgus instability.

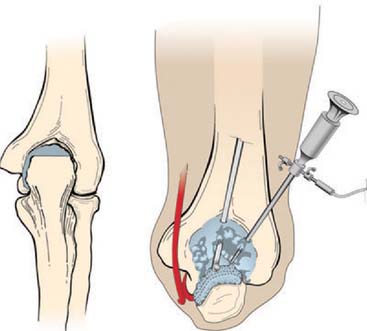

Evaluation of the posterior compartment uses direct posterior and posterolateral portals. Diagnostic arthroscopy evaluates presence of osteophytes on the posteromedial aspect of the olecranon, loose bodies, and any evidence of chondromalacia. Figure 39-4 illustrates removal of the olecranon osteophyte with a small osteotome placed at the margin of the osteophyte and normal olecranon (Fig. 39-5A). The motorized burr introduced through either the direct posterior portal or posterolateral portal may further contour the olecranon tip, as shown in Figure 39-5B. A lateral radiograph may be obtained intraoperatively to ensure adequate bone removal and that no bone debris remains in the soft tissues surrounding the elbow. It is important to remove only the osteophyte and not normal olecranon to prevent increased strain on the UCL during valgus loading.15 Once the osteophyte has been removed from the olecranon, the trochlea and olecranon fossa should be examined for osteophytes or kissing lesions, which should also be removed. It is important to recognize that the osteophytes occur on both the ulna and the humerus. Some nonthrowing athletes have a major component of direct extension overload without significant valgus stress. For these patients, the risk of developing UCL insufficiency following posterior decompression is much less compared with that of the throwing athletes and, therefore, débridement can be more aggressive, if necessary.

OSTEOCHONDRITIS DISSECANS

Lesions of the capitellum in young athletes must be differentiated as either Panner’s disease or osteochondritis dissecans (OCD). Panner’s disease is an osteochondrosis of the capitellum, which affects individuals younger than 10 years of age.24 Radiographic features include fissuring, irregularity, and fragmentation of the capitellum. Panner’s disease is usually self-limited and resolves spontaneously with radiographic reossification. In adolescent athletes, OCD is believed to be caused by repetitive radiocapitellar joint compression forces that result in cartilage and bone damage.10,13,25,28 Patients with capitellar OCD typically have a history of repetitive activity, such as throwing or gymnastics. Symptoms include lateral elbow pain associated with loss of motion. Locking and catching suggests the presence of intra-articular loose bodies. Physical examination most commonly demonstrates a 15 to 20 degree flexion contracture with crepitus and tenderness localized to the radiocapitellar joint. Plain radiographs demonstrate fragmented subchondral bone with lucencies and irregular ossification of the capitellum. Loose bodies may also be seen in the elbow joint on plain radiographs. MRI further delineates the avascular segment and loose bodies (Fig. 39-6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree