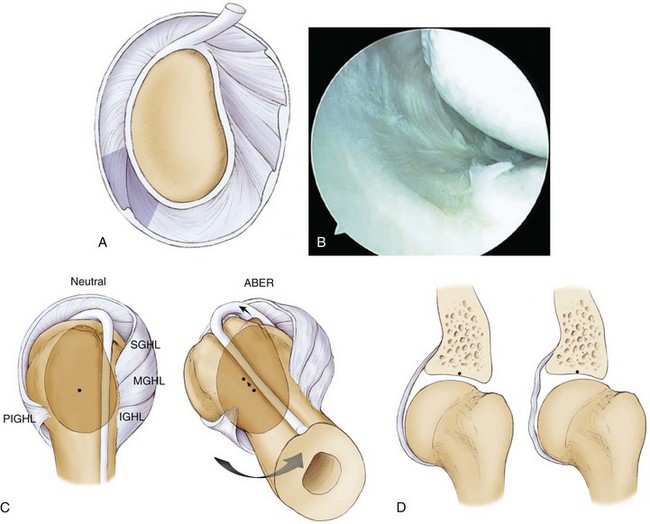

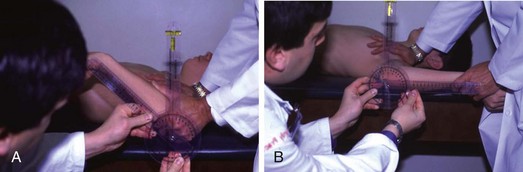

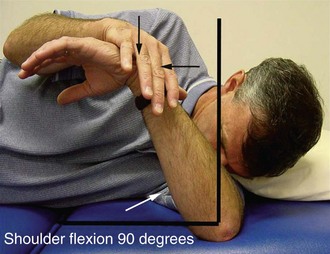

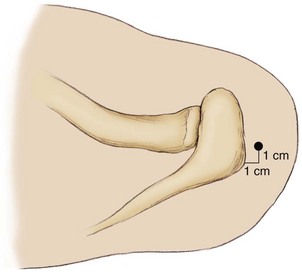

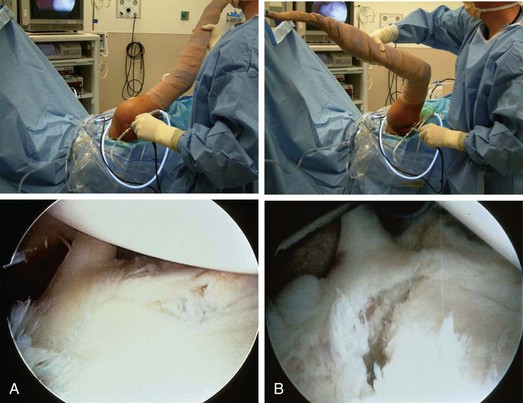

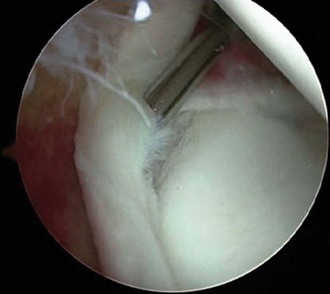

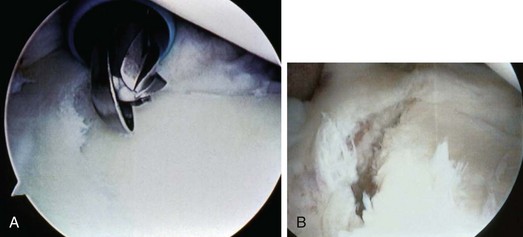

Chapter 11 The term internal impingement was initially used by Walch1 to describe contact of the undersurface of the rotator cuff with the posterior superior labrum in the abducted and externally rotated position. Jobe2 described progressive internal impingement caused by repetitive stretching of anterior capsular structures as the primary cause of shoulder pain in overhead athletes. Our treatment of disability in the throwing shoulder is predicated on the inciting lesion being an acquired contracture of the posteroinferior capsule.3 The posteroinferior capsular contracture alters the biomechanics of the joint and leads to a progressive pathologic cascade observed in the disabled throwing shoulder. Because of repetitive overuse, throwers are susceptible to the development of posterior shoulder muscle fatigue and weakness, including fatigue and weakness of the scapular stabilizers and rotator cuff. Posterior muscle weakness leads to failure to counteract the deceleration force of the arm during the follow-through phase of throwing. In the healthy throwing shoulder, a glenohumeral distraction force of up to 1.5 times body weight is generated during the deceleration phase of the throwing motion. This distraction force is counteracted by violent contraction of the posterior shoulder musculature at ball release, which protects the glenohumeral joint from abnormal forces and prevents development of pathologic changes in response to these forces. In the presence of posterior muscle weakness, as seen initially in the disabled thrower, the distraction force becomes focused on the area of the posterior inferior glenohumeral ligament (PIGHL) complex because of the position of the arm in forward flexion and adduction during the follow-through phase of throwing. Fibroblastic thickening and contracture of the PIGHL zone occur as a response to this distraction stress (Fig. 11-1A and B). PIGHL contracture causes a shift of the glenohumeral contact point posteriorly and superiorly in the abducted and externally rotated position4 (Fig. 11-1C). This shift allows clearance of the greater tuberosity over the posterosuperior glenoid rim, enabling hyperexternal rotation (unlike normal internal impingement). In addition, the posterosuperior shift causes a relaxation of the anterior capsular structures, which manifests as anterior pseudolaxity and allows even further hyperexternal rotation around the new glenohumeral rotation point (Fig. 11-1D). 1. Posterior muscle weakness, demonstrated by scapular asymmetry 2. PIGHL contracture, the inciting lesion—manifests as a glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD) in the throwing shoulder versus the nonthrowing shoulder 3. Superior labral anterior-posterior (SLAP) tear, type II—typically the anterior and posterior or posterior subtype (the “thrower’s SLAP”)5 4. Rotator cuff failure—generally partial undersurface and occasionally full-thickness tearing in the posterosuperior cuff 5. Anterior instability (anterior capsular attenuation or capsulolabral injury)—in approximately 10% of cases • Both exposed shoulder girdles are inspected from behind. • Note asymmetry in both shoulder height and scapular position. • The superior and inferior medial scapular angles are marked as a visual reference. • Dropped position of the acromion and elevation of the inferomedial angle of the scapula from the chest wall signify scapular protraction and antetilt and are evidence of scapular muscle weakness (Fig. 11-2). • Posterosuperior joint line—superior labral pathology. • Coracoid—Protraction of the scapula forces the coracoid into a more lateral position and places tension on the pectoralis minor tendon, causing tenderness at its insertion. • Superior scapular angle—Scapula infera places tension on the levator scapula muscle insertion, causing similar tenderness. • Measurements are made with the patient in the supine position with the scapula stabilized by anterior pressure on the shoulder against the examining table. A goniometer is used with carpenter’s level bubble chamber attached. • The arm is abducted 90 degrees to the body, scapular plane; internal rotation and ER are measured from a vertical reference point (perpendicular to floor) (Fig. 11-3). • The throwing shoulder is compared with the nonthrowing shoulder. • Internal rotation, ER, total motion arc (TMA), and GIRD of the throwing shoulder versus the nonthrowing shoulder are recorded. • Specificity of clinical tests for type II SLAP tears in these athletes has been determined.5 The Jobe relocation test is performed by placing the arm in maximal abduction and ER. Throwers with a posterior SLAP tear will experience pain in this position as a result of the unstable biceps anchor falling into the peel-back position. The discomfort is relieved with a posteriorly directed force to the front of the shoulder, which has been shown under direct arthroscopic visualization to reduce the labrum into the normal position.6 Patients start internal rotation “sleeper stretches” preoperatively for assessment of the extent of PIGHL contracture (Fig. 11-4). In general, 90% of patients with severe GIRD (more than 25 degrees) are able to decrease their internal rotation deficit to less than 20 degrees with 10 to 14 days of focused stretching. The remaining 10% are stretch “nonresponders” and are generally older athletes with long-standing GIRD and substantial thickening of the posteroinferior capsule. In these patients a posteroinferior capsulotomy is indicated to increase internal rotation at the time of surgery. Before the procedure is begun, it is important to have all anticipated instruments and materials needed for the surgery available and on the surgical field so that the procedure can be performed without unnecessary intraoperative delays (Table 11-1). Efficient performance of the procedure will avoid the dreaded scenario of attempting an arthroscopic repair in the distended, “watermelon” shoulder that can severely compromise the quality of the surgery. This cannot be overemphasized. As a general guideline, the type of repair described here should be accomplished in 20 to 40 minutes, depending on the associated pathologic processes. Superior labral tears in throwers may be associated with rotator cuff and anterior capsulolabral pathology. Treatment of these associated pathologic processes must be anticipated at the time of surgery. TABLE 11-1 Recommended Instruments for Arthroscopic Treatment of Pathologic Processes in the Throwing Shoulder PDS, polydioxanone; SLAP, superior labral anterior-posterior. Repairs in throwing athletes are performed through the following portals: • Anterior: main working portal; anchor placement in anterior labrum, knot tying • Posterolateral (portal of Wilmington): anchor placement and suture passage in posterior labrum (Fig. 11-5) • Anterosuperior: accessory portal; viewing and suture passage in anterior labrum or capsule (depending on associated pathologic changes) Diagnostic Arthroscopy and Surgical Techniques: Routine diagnostic arthroscopy is performed to ensure that all portions of the joint are inspected and no pathologic lesion is overlooked. In the disabled throwing shoulder, areas requiring particular attention include the following: Evidence of labral injury must be assessed carefully, as findings may be subtle (Box 11-1). An assessment is quickly made of the pathologic areas to be addressed, and a plan is made for the completion of the repair (Box 11-2). Drive-Through Sign: Before other cannulas or instruments are introduced, an assessment is made of laxity in the joint by testing for the drive-through sign. In a normal shoulder, capsular restraints prevent passage of the arthroscope from posterior to anterior at the midlevel of the humeral head or sweeping of the scope from superior to inferior along the anterior glenoid rim. The drive-through sign may be present in patients with a SLAP tear because of pseudolaxity from the loss of labral continuity around the glenoid rim.7 Peel-Back Test: The peel-back test is performed by removing the arm from traction and placing it into the abducted and externally rotated position. With a posterior SLAP lesion, the labrum can be observed to fall medially along the glenoid neck during this maneuver (Fig. 11-6). Anterior SLAP lesions will have a negative result for the peel-back test. After assessment of the biceps anchor, the probe is used to assess the undersurface of the rotator cuff and to estimate depth of partial-thickness tears, to determine the stability of the anterior inferior labrum, and to identify any redundancy in the anterior capsule.8 Specific steps are outlined in Box 11-3. 1: Placement of Secondary Portals An 8-mm cannula is used as a primary anterior working portal. An 18-gauge spinal needle is used to localize the cannula so that it can accommodate all necessary repairs, including anterosuperior anchor placement in the labrum and tying of posterosuperior anchor sutures. The cannula is readied near the skin surface, the spinal needle is used as a guide to the proper insertion angle, the spinal needle is withdrawn, and the cannula is inserted. An accessory 5-mm anterior portal may be placed, depending on the location of associated pathologic lesions requiring treatment. 2: Probing of Intra-articular Structures A probe is introduced in the anterior cannula for more careful assessment of stability of intra-articular structures. Normally, a sublabral sulcus with healthy-appearing articular cartilage can be seen extending up to 5 mm beneath the labrum. An unstable biceps root can easily be displaced with the probe medially along the glenoid neck8 (Fig. 11-7; see also Box 11-1). 3: Intra-articular Debridement A full-radius blade motorized shaver is used to gently debride loose and frayed tissue to prevent snagging of tissue with joint motion or potential loose bodies. 4: Preparation of Superior Labral Bone Bed An arthroscopic rasp is used to completely separate any remaining attachments in the injury area. A rasp is used because there is less risk of causing intrasubstance injury in the labrum than with an elevator. On occasion, some tenuous attachments from the labrum may be present medially, but the biceps anchor is still unstable. In these cases we routinely complete the lesion by removing these loose attachments before repair. All loose soft tissue is removed from the repair site carefully with the shaver. An arthroscopic bur is then used to remove cartilage along the superior glenoid rim to make a bleeding bone bed for labral repair (Fig. 11-8). This step is crucial to allow subsequent healing of the labrum back to the glenoid rim. We prefer a bur with a protective hood that is specifically designed to prevent damage to labral tissue during this step (SLAP bur, Stryker Endoscopy, San Jose, CA). No suction is used while the bur is on to ensure that tissue is not inadvertently sucked into the instrument.

Arthroscopic Treatment of the Disabled Throwing Shoulder

Part 1 Arthroscopic Treatment of Internal Impingement

Preoperative Considerations

Physical Examination

Indications and Contraindications

Surgical Planning

Instrument

Use

Camera

30-Degree lens

Shoulder arthroscopy set (Arthrex)

Arthroscopic rasp

Labral detachment

Arthroscopic elevator

Arthroscopic cannulas

8 mm

Anterior working portal

5 mm

Anterior accessory portal

Motorized shaver

Debridement

Full-radius blade (Stryker)

Motorized bur

Preparation of glenoid rim

Protective hood; SLAP bur (Stryker)

Arthroscopic bovie

Posterior capsulotomy

Long handle, hook tip (Linvatec)

Bio-Suture Tak anchors (Arthrex)

Labral fixation

No. 1 PDS suture

SLAP fixation

Free suture: capsular plication

SutureLasso passer device (Arthrex)

Suture passage: superior labrum

Right-angled

Birdbeak suture retrievers (Arthrex)

Suture passage

45-Degree

Posterior superior labrum

22-Degree

Anterior superior labrum

Suture-passer set (e.g., Spectrum)

Suture passage

Straight

Longitudinal rotator cuff tear

45-Degree curved hook (left and right)

Capsular plication

Surgical Technique

Surgical Landmarks, Incisions, and Portals

Examination

Provocative Tests

Specific Steps

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree