Chapter 32 Arthroscopic Meniscal Resection

The menisci act to cushion the loads that cross the knee joint by mediating these forces through both longitudinal and radial fibers within its core structure. These fibers distribute hoop stresses as well as shear stresses across the entire meniscus. Maintenance of as much meniscal tissue as possible is therefore essential in decreasing overall contact stresses across the knee joint. However, the menisci are mostly avascular structures, as illustrated in landmark work done by Arnoczky and Warren, which has helped our understanding of the limited healing potential of torn meniscus.1

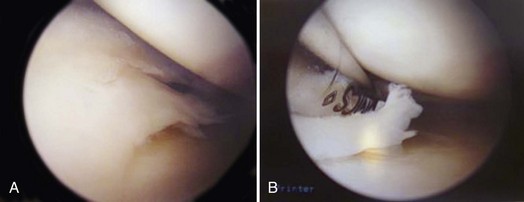

The perimeniscal capillary plexus arises from the medial and lateral superior and inferior geniculate arteries and supplies approximately the peripheral third of the menisci. The lateral meniscus has even less perfusion than the medial meniscus, given the lack of capsular attachment at the popliteal hiatus. The zones of the menisci are commonly described in relation to this limited blood supply as red-red in the well-perfused periphery, red-white in the middle, and white-white in the avascular center. Generally speaking, if a tear is more than 5 mm from the meniscosynovial junction, it is considered avascular.1 This imperfect matchup of poor perfusion to an essential structure within our knee leaves scarce amount of tissue that is amenable to healing and repair. It is for this reason that most meniscal tears that are approached surgically undergo resection rather than repair (Fig. 32-1).

According to the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgeons, arthroscopic meniscal resection, code 29881, heads the list of the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes in the candidate case submissions for Part II of the orthopedic certification examination. Medial meniscal tears, code 836.0, and lateral meniscal tears, code 836.1, are in the top three ICD-9 codes submitted for the examination as well.8

It is important to distinguish arthroscopy for meniscal tears from arthroscopic débridement for degenerative joint disease, which has received much negative press recently as providing no benefit when compared with nonoperative treatment.9 Meniscal tears can be described by zone, as noted, or by type of tear. The first classification deals with healing potential, whereas the more commonly used categorization is by type, which describes the orientation of the tear pattern. Tears can be vertical, both longitudinal or radial, as well as horizontal, or they can be complex. Displaceable tears consist of parrot beak, flap, horizontal cleavage, and bucket handle types.11

In addition to vascularity and type, chronicity of the tear and associated injuries also play an important role in classifying meniscal tears. Acute tears, less than 2 to 3 weeks old, are more amenable to repair, whereas more chronic tears become ragged and frayed, making the tissue less likely to be repaired successfully. Associated injuries, such as anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears, also affect meniscal tears. Meniscal tears are seen in over 50% of knees with associated ACL tears. It has been shown that ACL-deficient knees fare worse with partial meniscectomy than stable knees.2 Some believe that a short (<1-cm) stable tear may be left untreated at the time of ACL reconstruction with no meniscal complications noted in follow-up.12 The degree of degenerative change in the compartment with the diagnosed meniscal tear must also be assessed, because the more advanced the arthritis, the less chance a patient will likely benefit from arthroscopic meniscal resection.

Several patient-related factors to consider in the categorization of meniscal tears are age, activity level, ability to comply with physical therapy, and body mass index. Young athletes have a higher success rate than older, more sedentary patients as far as meniscal repairs are concerned. Partial meniscectomy requires less cooperation with physical therapy from the patient than meniscal repair, which may require an extended period of limited weight bearing and range of motion. An inability to participate in a more stringent rehabilitation protocol may make resection a better choice than repair. Finally, significant associations have been shown between an increase in a patient’s body mass index (BMI) and the number of meniscal surgeries in both genders, including obese and overweight adults, especially in those with a BMI higher than 40.6

Clinical Assessment

Meniscal tears are common. Many studies have found that even in asymptomatic knees, the rate of meniscal tears detected on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is very high. One recent study has shown that in patients with radiographic signs of osteoarthritis, more than 60% of patients were found to have meniscal tears on MRI scans, regardless of the presence or lack of symptoms. In knees without radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis, meniscus tears were seen in 23% of asymptomatic knees.3,7,14

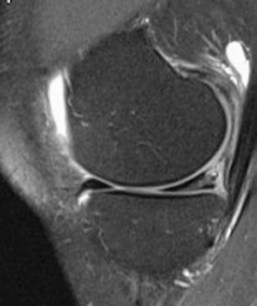

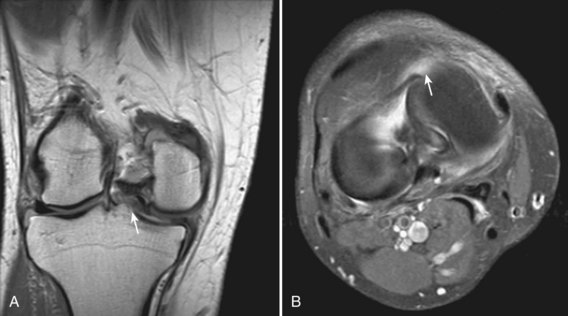

MRI is a useful tool for assessing meniscal tears, but should be used to confirm the clinical suspicion of a tear, rather than to screen for tears (Fig. 32-2). Another important application is to use the images, especially in multiple planes, to help anticipate arthroscopic findings (Fig. 32-3).

MRI findings alone should never be used to dictate treatment of patients with meniscal tears. Many patients present to the orthopedic surgeon with positive MRI scans, never having undergone radiographs of the knee or even an appropriate physical examination. Occasionally, a weight-bearing radiograph is sufficient to diagnose and determine a treatment plan for a patient and obviates the need for MRI, because it would add no further information that would change management. Radiographic findings always need to be properly correlated to the patient’s complaints and the surgeon’s physical examination findings. An acute injury with subsequent mechanical symptoms rather than a vague spontaneous onset of symptoms, along with findings of joint line tenderness and rotatory pain, with provocative tests such as the McMurray and Apley grind tests, are likely to correlate with symptomatic meniscal tears.11

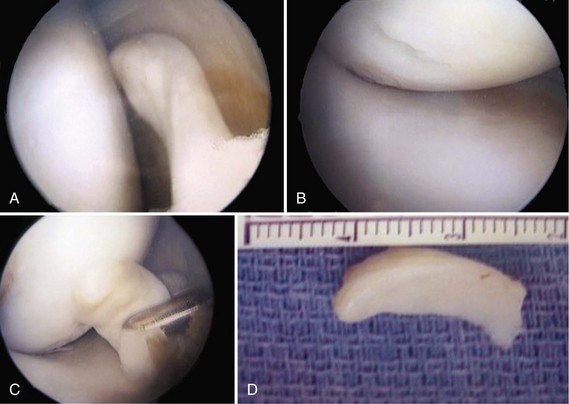

Once the decision has been made to proceed with arthroscopic surgery, the procedure should not be postponed for long to avoid articular cartilage damage resulting from unstable meniscal flaps (Fig. 32-4). Rarely, a delay of several weeks is necessary to allow for a decrease in swelling and to regain a functional range of motion of the knee.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree