Jess H. Lonner

Robert Booth Jr

Arthrodesis and Resection Arthroplasty of the Knee

INDICATIONS FOR KNEE ARTHRODESIS

FUNCTION OF A KNEE ARTHRODESIS

GENERAL INTRAOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

CONVERSION FROM ARTHRODESIS TO TOTAL KNEE ARTHROPLASTY

ALTERNATIVES TO ARTHRODESIS INCLUDING RESECTION ARTHROPLASTY

INTRODUCTION

Arthrodesis and resection arthroplasty of the knee should be regarded as alternatives to revision total knee arthroplasty (TKA). Although, arthrodesis of the knee has been performed since the early 20th century for the pain and instability associated with advanced arthritis, posttraumatic arthritis, Charcot arthropathy, infectious arthritis, poliomyelitis, and tumor reconstruction.1–10 Presently, the most common indication for a knee fusion is pain and instability in an unreconstructable knee following an infected knee arthroplasty.11–17 Resection arthroplasty of the knee has generally been reserved for those patients too medically debilitated to undergo an extensive revision knee arthroplasty, knee arthrodesis, or unwilling to undergo above-knee amputation. This chapter focuses on modern indications for knee fusion, surgical techniques, results, and complications of these procedures as well as alternatives including resection arthroplasty.

INDICATIONS FOR KNEE ARTHRODESIS

TKA was formerly complicated by early failures and high rates of revision in young vigorously active patients.16 As a result, knee fusion was previously considered for pain and instability of the knee in this patient population following tumor reconstruction, posttraumatic arthritis, or Charcot gonarthrosis. However, the indications for TKA have been expanded and more appropriately fit the demands of younger patients.18

Arthrodesis may be used in tumor resections that require large resections in which the joint surface may not be preserved and where an adequate soft tissue plane exists between the resected tumor margin and the posterior neurovascular structures. Tumors that do not meet these criteria may be better managed with above-knee amputation. Enneking and Shirley19 performed knee arthrodeses in 20 patients with a mean age of 25 years (range: 10 to 52 years) with recurrent tumors about the knee, of which 15 patients were able to resume their previous occupations.

Knee fusion is most commonly indicated in a patient with an unreconstructable knee following failed TKA, most commonly secondary to infection. Although, it can be difficult to ascertain which situations are unsalvageable and when a knee fusion would provide a better and more reliable outcome than a multiply revised TKA. Husted et al.20 recently reported on 24 infected primary TKAs, of which 17 underwent a two-stage revision arthroplasty. The other seven were unable to have a revision arthroplasty and required an arthrodesis procedure. Fifteen of the revision arthroplasties were considered successful with eradication of infection; however, eight of these patients continued to have pain. The remaining two patients required an arthrodesis and an above-knee amputation. The incidence of failed two-stage exchange arthroplasty for infection following a primary total knee replacement requiring a knee fusion ranges from 6% to 13%.21,22 The failure rate following a revision total knee replacement that becomes infected is considerably higher.11 Hanssen et al.11 studied 24 patients who had an infected revision TKA of which 12 (50%) patients eventually needed a knee arthrodesis procedure of which 10 were successful. Four of the original 24 (17%) patients went on to an above-knee amputation. Knutson et al.23,24 advocated arthrodesis when there is infection associated with soft tissue problems, virulent, and/or resistant organisms.24 Accordingly, a knee arthrodesis may even be considered in initial cases of infected primary TKA where a reimplantation would have a high rate of failure.

Wilde and Stearns25 noted that greater degrees of bone loss were associated with decreased fusion rates and suggested that failure of a two-stage implantation may be an indication for arthrodesis before multiple failures lead to more bone loss. Behr et al.26 demonstrated a decrease in the fusion rate following constrained prostheses presumably from greater bone resection following implant removal.26

In summary, knees with large metaphyseal bone loss, inadequate ligamentous restraints, multiple revision failures, inadequate soft tissue coverage with extensor mechanism loss, and infection with virulent organisms should be considered for arthrodesis. It may be difficult for the surgeon as well as the patient to decide, because preserving motion with a total knee revision arthroplasty is an attractive option. Although the surgeon may consider an arthrodesis to be a poor outcome, it is more efficient and functional than an above-knee amputation.27 Arthrodesis following infected knee arthroplasty has a low risk of reinfection16,23,28,29 and provides a stable, pain-free limb.

Factors leading to above-knee amputation following TKA include multiple revisions with chronic infection, severe bone loss, and intractable pain.30 Isiklar et al.30 reported nine above-knee amputations for complications after knee arthroplasty of which only two of the eight patients were ambulatory. Pring31 also reported limited ambulation in a series of 23 patients with above-knee amputation following knee arthroplasty in which only 7 (30%) were ambulatory. Additionally, the energy expenditure is greater following amputation than it is following fusions.27,32

The compensatory mechanisms for ambulation with a successful knee arthrodesis include increased pelvic tilt, increased ipsilateral hip abduction, and increased ipsilateral ankle dorsiflexion.32 As a result, ipsilateral hip and ankle arthritis may preclude effective compensatory efforts during ambulation. Patients with degenerative arthritis of the spine are also poor candidates for knee fusion because of the compensatory pelvic tilt required during ambulation and an increase in the forces distributed across the lumbar spine.16 A knee fusion increases the energy required for ambulation by 25% to 30% when compared to normal walking.32 In contrast, an above-knee amputation requires 25% greater energy expenditure than a knee fusion. By summation, the energy required for ambulation with a combination of an amputation and contralateral fusion would make ambulation prohibitive. Contraindications to knee fusion include contralateral knee amputation, contralateral knee or hip fusion, and patients with ipsilateral hip and ankle degenerative changes.16 Other relative contraindications include nonambulatory patients and those patients with comorbid medical illnesses that would preclude a large surgical procedure.

FUNCTION OF A KNEE ARTHRODESIS

In a series of knee arthrodesis patients who were compared to a group of constrained knee arthroplasty patients and to above-knee amputation patients, the arthrodesis patients performed the most physically demanding activities and had superior stability (less symptomatic giving way).33 Benson et al.34 evaluated nine patients with knee arthrodeses versus a control group of nine patients with primary knee arthroplasties. Interestingly, the SF-36 scores were similar in both groups for pain, health, vitality, social, and emotional health. Rud and Jensen35 reported a series of knee arthrodeses of which 18 of 23 patients returned to work. Enneking and Shirley19 reported a series in which 15 of 20 patients resumed their previous occupation, and 16 patients ambulated without a cane or walker. Several of these patients were highly active including patients who golfed, water-skied, sailed, hunted, and played racquetball. Other authors have indicated that knee arthrodesis patients had difficulty with stairs, rugs, and ladders and those who did heavy work rarely returned to that job.36 Rand et al.37 described a series of 28 knee arthrodesis patients of whom 9 patients with a successful arthrodesis could walk more than six blocks, and 7 walked one to three blocks. In a report of 13 successful Ilizarov knee fusions, all 13 patients required a cane for ambulation.38 Garberina et al.39 also reported a series of 13 successful Ilizarov knee fusions of whom 9 patients used a cane or walker, only 2 patients did not require any assistive devices and 6 of the 9 patients could walk one to five blocks.

In consideration of overall function, patients can expect a stable, painless extremity with difficulty climbing stairs and sitting in crowded venues. One, however, cannot underestimate the degree of social difficulty associated with a knee arthrodesis. Kim et al.40 reported that 17 of 30 knee fusion patients who were converted to TKA had previously attempted suicide because they were unhappy with their leg preoperatively. Preoperative counseling prior to fusion and patient selection are essential in preventing patients from developing unrealistic postoperative expectations.

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

Comorbid medical conditions should be optimized prior to knee arthrodesis. Host factors such as smoking, diabetes, and obesity increase the risk of wound problems, nonunion, and infection. Chemotherapy and radiation treatment for tumor resections should be completed in advance in order to minimize wound-healing problems.

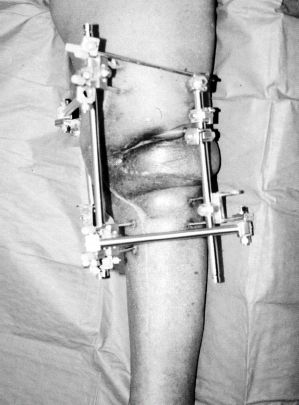

Previous skin incisions must be critically inspected and considered in order to prevent wound necrosis. Wound complications often occur in patients with infected knee arthroplasties as Rand and Bryan41 evaluated the outcome of failed knee arthrodeses and found that 8 of 25 had soft tissue complications including hematoma, drainage, and flap necrosis. If wound difficulties are anticipated, a preoperative plastic surgery consult is wise. In addition, preoperative vascular evaluation may be necessary in the presence of diminished peripheral pulses. Intraoperative Doppler assessment of the pedal pulses may also be helpful. Vascular embarrassment can occur during acute bone compression due to the extensive scarring that occurs in the posterior aspect of the knee following a TKA.19 Knee fusion surgery is often plagued by considerable blood loss and long operative times.13,42 Donley et al.42 reported on a series of 20 knee arthrodeses performed with a long intramedullary nail with a mean estimated blood loss of 1,574 mL (range: 520 to 3,200 mL), a mean transfusion of 3.9 units of (range: 0 to 7) packed red blood cells, and a mean operative time of 4.1 hours (range: 2.5 to 8.3 hours) (Fig. 57-1).

FIGURE 57-1. Clinical photograph of a 67-year-old woman following a resection arthroplasty and knee arthrodesis with multiplanar external fixation. Note the gastrocnemius flap for soft tissue coverage.

Shortening of the affected extremity typically follows knee fusion, and the leg length discrepancy has ranged from 2.5 to 6.4 cm.26,38,43–46 This discrepancy can be best estimated from a preoperative teleoroentgenogram (long 51-inch radiograph that includes the hips to the ankles). In cases where the leg length discrepancy is substantial, a concomitant lengthening procedure can be performed using an osteotomy combined with an external fixator.47–50 Hessman et al.49 reported a series of knee fusions that were simultaneously lengthened 5 cm with an Ilizarov external fixator.

Reconstruction of the large bone and soft tissue defects following tumor resection can be challenging and requires appropriate preoperative planning. Length-preserving reconstructive techniques include vascularized fibula grafts, allografts, and distal femur and proximal tibial sliding grafts.19,50–52 Specific allografts need to be ordered in advance, and musculoskeletal tissue banks often require radiographs with magnification markers for accurate allograft sizing.

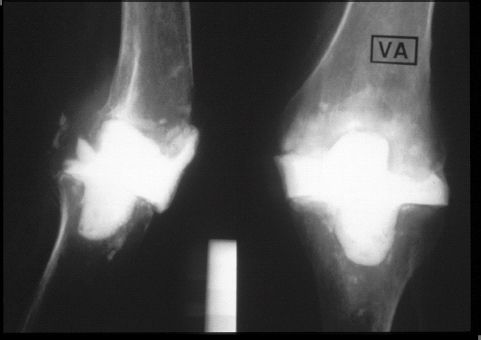

The fusion rates are higher when the initial infection is eradicated and there are more options for fixation.53–59 The initial surgery consists of surgical debridement, removal of components, and insertion of an antibiotic-impregnated cement spacer (Fig. 57-2). Several authors have reported good results with the careful use of intramedullary nails after staged eradication of infection.25,54 Wilde and Stearns25 advocated preoperative knee aspiration and normalization of lab serologies prior to fusion with an intramedullary nail. Despite these precautions, 5 of 12 patients developed positive cultures at the time of fusion and 2 of these patients developed a subsequent infection after union. These two patients had to undergo nail removal to eradicate the infection. Fortunately, to our knowledge, there have been no reports of osteomyelitis of the femur or tibia following long intramedullary nails for knee fusion.60 However, several authors have also demonstrated that one-stage fusion using an intramedullary nail for infected TKA was safe, effective, and without recurrent infection in the absence of gross purulence and gram-positive organisms.46,58,61 Puranen et al.46 recommended the use of intramedullary nails for infection in a staged fashion following an 8- to 10-week interval of a cement spacer and normalization of serologic markers. Surgeons may also consider using intraoperative frozen sections from the knee to assess the number of polymorphonuclear leukocytes per high-powered field62,63 as a surrogate marker of persistant infection. In situations with virulent or polymicrobial infections with large bone loss, the authors recommend circular or biplanar external fixation.

FIGURE 57-2. Anterior-posterior and lateral radiographs of the knee of an 82-year-old woman following resection arthroplasty and placement of an antibiotic laden cement spacerblock.

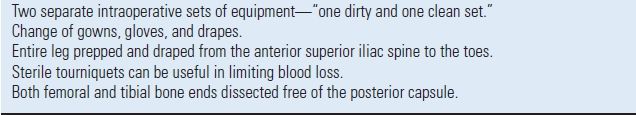

GENERAL INTRAOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

There are several general operative principles that should be followed with knee arthrodesis procedures regardless of the indications or techniques chosen (Table 57.1). Since contamination is a major concern, two separate intraoperative sets are required—“one dirty and one clean set,” for tumor resections and infections. The “dirty set” is used during the resection and the “clean set” is used for the reconstruction. This technique helps to minimize contamination of the unaffected tissues with residual bacteria or tumor cells. In addition, gowns, gloves, and drapes should be changed between steps to minimize contamination. In general, the entire leg should be prepped and draped from the anterior superior iliac spine to the toes to aid in determining rotational alignment. Sterile tourniquets can be useful in limiting blood loss. Both femoral and tibial bone ends must be adequately dissected free of the posterior capsule to allow good bone apposition without soft tissue interposition. Acute shortening can result in kinking of arteries and loss of pulses with vascular embarrassment.

TABLE 57.1 General Intraoperative Principles

The optimal sagittal and coronal plane alignment of a knee arthrodesis is somewhat controversial. The majority of knee fusions are placed in 0 degrees of extension in order to prevent limb shortening. However, several authors have advocated 5 to 10 degrees of flexion.1,36 Siller and Hadjipavlou36 noted a more efficient gait with 15 degrees of flexion, due to the change in the push-off direction of the gastrocnemius muscle. The gastrocnemius at 0 degrees of knee flexion has a vertical thrust, but at 15 degrees there is more of a horizontal or propulsive thrust. Accordingly, 10 to 15 degrees of flexion may be preferable and allows for better sitting position and improves gait, yet still results in a 25% increase in energy expenditure when compared to a normal population.27 However, 15 degrees of flexion also correlates to approximately 2 cm of shortening, and many surgeons are reluctant to increase the leg length discrepancy. Conway et al.32 studied the optimal position of an artificially fused knee in 10 healthy volunteers with the knee fixed at 20 and 0 degrees of flexion. Four of ten of the volunteers selected a faster walking speed at 20 degrees when compared to 0 degrees. Ideal frontal plane alignment has been reported as 5 to 7 degrees of valgus.46

Maximum bone contact has been noted by several authors to be extremely important for optimizing the outcome of knee arthrodesis.37,64,65 Charnley66 attributed a 98% success rate in 169 of 171 fusion procedures to “two perfectly coapted surfaces of cancellous bone with intact circulation.” Hagemann et al.65 and Woods et al.64 also determined that the most important factor for a successful fusion was good bone contact. Bone contact diminishes with increasing degrees of bone loss especially after hinged knee prostheses and tumor resections.23,37,43,67 Rand et al.,37 reported a series of knee arthrodeses for failed TKA, of which seven were hinged prostheses and four of these seven went on to nonunion. Brodersen43 reported only five successful fusions following nine arthrodeses after failed hinged prostheses. The authors felt that the four nonunions were secondary to the large loss of metaphyseal bone stock.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree