Chapter 13 Applied Behavioral Theory and Adherence

Models for Practice

Changes in the Health Care Environment: Health Care Delivery and Reimbursement

Role of Lifestyle in Morbidity and Mortality

Fundamental Relationship Between Patient and Practitioner in the Therapeutic Process

Behavioral Theories to Inform Practice, Promote Adherence, and Facilitate Health Behavior Change

The Patient-Practitioner Collaborative Model

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to:

1. Discuss the role of the patient-practitioner relationship as a part of the therapeutic process.

2. Identify the primary factors that affect adherence, including patient characteristics, disease variables, intervention variables, and patient-practitioner variables.

3. Compare and contrast the major behavioral theories or models for promoting adherence and behavioral changes.

4. Selectively and appropriately incorporate elements of these models into patient care.

5. Apply the patient-practitioner collaborative model to clinical scenarios.

6. Apply the Transtheoretical Model of Change to facilitate adherence.

Changes in the health care environment: health care delivery and reimbursement

One stimulus focusing more attention to lifestyle modification during the clinical encounter is the increasing use of the Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS).1 This is a set of common data indicators for the examination of managed care organization performance that was initially developed in the 1990s by the National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA). The latest version of HEDIS requires managed care organizations to report on more than 75 prevention-oriented indicators across eight domains of care (e.g., obesity, diabetes, hypertension).1

In 2006, the Tax Relief and Health Care Act (TRHCA, PL 109-432) established the physician quality reporting system under the jurisdiction of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). This plan identified Physician Quality Reporting Indicators (PQRI) to incentivize payment for practitioners (including physical therapists) to monitor and report on health-related symptoms in patients (e.g., blood pressure, balance risk) in order to identify costly conditions earlier and implement prevention strategies.2 This focus on prevention offers physical therapists increasing opportunity to apply adherence and health behavior change strategies with patients.

The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (established by PL 105-33) was enacted to reduce health care spending by $160 billion between the years 1998 and 2002.3 Since that time, physical therapists, especially those providing care for Medicare beneficiaries, have been required to focus on facilitating adherence and producing successful and effective patient outcomes under increasing conditions of cost-containment and payment scrutiny. More recent federal legislation promises to further influence the delivery of health care service models in the United States. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PL 111-148)4 of 2010 offers three major programs that directly affect physical therapists:

• Accountable care organizations

• Centers for Medicare and Medicaid services’ medical home or patient-centered medical home models

Accountable care organizations

Accountable care organizations (ACOs) are a direct response to Congress’ continued efforts to reduce spending in health care, by authorizing the development of ACOs under both Medicaid and Medicare programs. ACOs would authorize specific groupings of health professions to provide care while saving on unnecessary expenditures. At this time, physical therapists are not expressly included as eligible participants in ACOs, but advocacy groups such as the American Physical Therapy Association are supporting inclusion among eligible practitioners because interventions have been shown to decrease overall patient care costs.4

Medicare innovation models

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PL 111-148) also establishes the Medicare and Medicaid Innovation Center “to research, develop, test, and expand innovative payment and delivery arrangements to improve the quality and reduce the cost of care provided to patients,”5 especially in situations such as outpatient settings, that do not require referral by or plan of care established by a physician.5 Physical therapists with the ability to facilitate patient adherence will be well positioned to demonstrate improved efficiency in the delivery of quality care.

Medical home or patient-centered medical home models

The final promising model proposed in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 is the CMS Medical Home or Patient-Centered Medical Home model designed to provide comprehensive primary care partnerships between individual patients or families and their health providers.6 Like the Direct Access model, the purpose is to develop and test service delivery models to decrease health care costs. Although unknown at this time, the impact on physical therapy could be significant if physical therapists become participants in the medical home model.6 Although the effects of current and future health care legislation are uncertain, it is clear that practitioners will be required to produce effective and economical patient outcomes. This will require physical therapists to facilitate adherence and the patient’s ability to self-manage conditions.

Role of lifestyle in morbidity and mortality

There is significant evidence that lifestyle risks can contribute to premature morbidity and mortality. Healthy People 2020 targets several determinants of health, including diet, physical activity, and tobacco use.7 More than 60% of the deaths in the United States in 2007 are attributable to chronic illnesses such as heart disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer, and chronic lower respiratory diseases.8 Lifestyle-related behaviors can contribute to all of these diseases.

Research has demonstrated that intervening with inactive patients is likely to be helpful because virtually all individuals can benefit from some form of regular activity. According to the Surgeon General’s Vision for a Fit Nation 2010, about two thirds of adults and one third of children are overweight or obese.9,10 Non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics are more likely to be obese than non-Hispanic whites. The prevalence of obesity in adults was almost 34% in 2007-2008 and was slightly higher in women than in men.9 The annual medical-related costs are estimated at $147 billion. Each year, obese workers cost their employers an estimated $644 more than their counterparts of normal weight.11

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services reports that more than 80% of adults do not meet the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for aerobic and strengthening exercise.12 Factors associated with participation in physical activity include postsecondary education, higher income, social support, safe place to exercise, and self-efficacy (belief in ability to perform the exercises). Conversely, those who are overweight or obese or who have lower income or perception of poor health are less likely to engage in physical activity. People who reside in rural communities or have a lack of motivation are also less inclined to perform regular exercise.7

Fundamental relationship between patient and practitioner in the therapeutic process

Physical therapists should integrate adherence and lifestyle counseling into their practices for a variety of reasons. Reports of adherence rates to supervised exercise, as is seen in cardiac rehabilitation or other outpatient programs, range from 70% to 94%,13,14 whereas adherence to home exercise programs is significantly less. Taal and associates,15 in a study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, found that 6% had difficulty adhering to a physical therapy regimen in the clinic, whereas 28% had difficulty adhering to a home exercise program. Nonadherence can take the form of the patient doing less or more of the prescribed intervention, never starting, or quitting prematurely. Each of these variations might represent a potential threat to the patient’s recovery and level of function. Degree of adherence should be assessed at each visit to help determine risk versus benefits to overall recovery. Factors related to adherence include the patient’s personal characteristics, variables associated directly with the disease or injury, intervention variables, and those having to do with the relationship between the patient and the practitioner (Table 13–1).

Table 13–1 Thirty-Six Factors Related to Treatment Nonadherence

| Variables | Factors |

|---|---|

| Personal variables (patient) | Characteristics of the individual Sensory disturbance Forgetfulness Lack of understanding Conflicting health benefits Competing sociocultural concepts of disease and treatment Apathy and pessimism Previous history of nonadherence Failure to recognize need for treatment Health beliefs Dissatisfaction with practitioner Lack of social support Family instability Environment that supports nonadherence Conflicting demands (e.g., poverty, unemployment) Lack of resources |

| Disease variables | Chronicity of condition Stability of symptoms Characteristics of the disorder |

| Treatment variables | Characteristics of treatment setting Absence of continuity of care Long waiting time Long time between referral and appointment Timing of referral Absence of individual appointment Inconvenience Inadequate supervision by professionals Characteristics of treatment Complexity of treatment Duration of treatment Expense |

| Relationship variables (patient-practitioner) | Inadequate communication Poor rapport Attitudinal and behavioral conflicts Failure of practitioner to elicit feedback from patient Patient dissatisfaction |

From Meichenbaum D, Turk DC. Facilitating Treatment Adherence. New York: Plenum, 1987.

Physical therapists know that they are more likely to achieve patient cooperation or adherence when they try to understand the patient’s perspective about the condition and its effects. This perspective is the patient’s unique interpretation that incorporates sociocultural, emotional, and cognitive factors as well as sense of uniqueness, or the perceived probability that he or she is like or different than others with the same condition, all of which determine the patient’s response to illness.16–20 The patient’s perspective and the process of trying to understand it can be contrasted to the student-teacher model, in which the student is the “empty vessel” into which the teacher pours his or her wisdom and knowledge. Using the same model with patients and practitioners, then, the practitioner gives the patient information (through teaching, written materials, or classes) about the condition, and if the patient does not improve, the practitioner may conclude that the “vessel” is not yet full and more information needs to be provided. However, more information does not necessarily lead to a change in behavior.21,22 Following a treatment plan requires that the patient

• Knows when to enact the plan

• Has the psychomotor skills to perform the plan, and

• Remains motivated to follow through until the problem resolves.

Thus, although knowledge of the condition is important, the patient’s initial and long-term motivation are critical elements. To understand them, the therapist must understand the patient’s perspective. Therapists are more likely to facilitate change in the patient’s health behaviors by understanding the patient’s belief system, which is usually rational and based on culture, past experiences, and support systems.21–23

The ability to effectively understand the patient’s perspective will be increasingly important as changes in health care affect practice. Because of decreases in health care resources, therapists will be under increased pressure to maximize those scarce resources and yet continue to provide quality care for their patients. This will undoubtedly transfer much of the responsibility to the patients themselves and to their families. Designing therapeutic interventions with the highest likelihood of patient follow-through and adherence will be an essential factor in assessing patient outcomes.21,23 In response to societal needs and demands, increased emphasis on patient education, prevention, and health promotion is found in federal guidelines (Table 13–2) and in the policies and guidelines of the American Physical Therapy Association.7,10,24

Table 13–2 Examples of Guidelines for Patient Education, Health Promotion, and Prevention

Explanatory models in clinical practice

Kleinman initiated the concept of explanatory models to analyze problems that may arise between the patient and therapist during the clinical encounter.25 Kleinman defined explanatory models as the “notions patients, families, and practitioners have about a specific illness episode.”25 These explanatory models represent the patient’s attempt to make sense of the change from “ease” to “disease.” These beliefs often incorporate an attempt by the patient to self-disprove and ascribe a course to the condition. The patient’s diagnosis and causal beliefs bring into play beliefs about the likely consequences of the condition, the time before the condition resolves, and the interventions (both prescribed and home remedies).25 Kleinman and others22,25,26 speculate that the effectiveness of clinical communication and the patient’s health outcome may be a function of the extent of discrepancy between the patient’s and the practitioner’s explanatory model. For example, if a patient comes to physical therapy with the expectation that the therapist will fix the problem using massage for muscle pain, but the therapist expects to engage the patient in a home exercise program in a single visit, there will likely be a conflict in their interactions, or disappointment when either realizes the other is not meeting expectations.

Every therapist has one or more explanatory models in mind when working with patients. These models usually develop by thinking about the patient’s goals and needs, strategies to understand more about a patient’s receptivity to change, and strategies to engage the patient in his or her self-care at home. Just as a patient comes to the clinic with ideas about his or her condition, its immediate and long-term consequences, and the types of treatment that have and have not helped, therapists have their own beliefs for explaining the cause of the patient’s condition and anticipating the patient’s response to intervention. The therapist uses this explanatory framework, or model, to guide patient evaluation and decision making about patient management. These models may reflect beliefs about teaching and learning or motivation and behavioral change. The patient also comes with certain beliefs and expectations about what he or she wants from the provider about the sources and consequences of the illness. Using a set of simple questions proposed by Kleinman25 (Box 13-1) can help clarify the patient’s beliefs and goals.

Box 13-1 Kleinman’s Questions

1. What do you think caused the problem?

2. Why do you think it happened when it did?

3. What do you think your sickness does to you? How does it work?

4. How severe is your sickness? Will it have a short course?

5. What kind of treatment do you think you should receive?

6. What are the most important results you hope to receive from this treatment?

7. What are the chief problems your sickness has caused for you?

Data from Kleinman A, Eisenberg L, Good B. Culture, illness, and care: clinical lessons from anthropologic and cross-cultural research. Ann Intern Med 1978;88:251-258.

The biomedical model has dominated the explanatory frameworks shared by many health care practitioners in Western societies. It focused on pathology and the disease process, the physical symptoms that resulted from the disease, and the medication interventions intended to resolve the problem.27 Although this model was initially useful, its deficiencies as a comprehensive framework for patient management have become increasingly apparent. The model became more focused on the critical importance of patient outcomes and addressing the patient’s functional needs and health status rather than just documenting changes in physical impairment measures (e.g., range of motion or strength) and assuming those changes will result in a positive functional outcomes in patients’ lives.28,29 Such emphasis draws the therapist’s attention to the patient’s perspective because it requires that the therapist know the patient’s functional goals. However, this emphasis ignores other elements of the patient’s explanatory model that may affect treatment adherence (see Box 13-1).

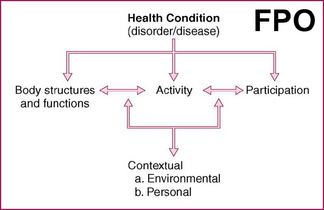

Another example of an explanatory model is an enablement schema, such as the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF). This model was endorsed by all 191 member states of the World Health Organization (WHO) at its 54th World Health Assembly in 2001.30 A model like the ICF provides therapists with common terms used to clearly illustrate the importance of facilitating physical function (i.e. altering body structure) to allow personal or social engagement (i.e., participation) (Figure 13-1). For example, a patient who has a disease like diabetes, which results in peripheral vascular disease and a subsequent lower extremity amputation, has several bodily structures and functions involved as a result of the pathology and the medical intervention. In turn, these may lead to limitations in the person’s ability to participate in certain activities. As seen in Figure 13-1, enablement not only involves the physical levels of changes in body systems but also reflects ability for engagement and participation in society and the fulfillment of social roles. The physical therapist’s primary role in facilitating patient movement and enhancing function has to do with change at both the individual and societal levels.30 Achieving these goals requires that the therapist explore the patient’s treatment goals and explanatory model to determine potential intervention barriers.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree