42. Antiviral therapy

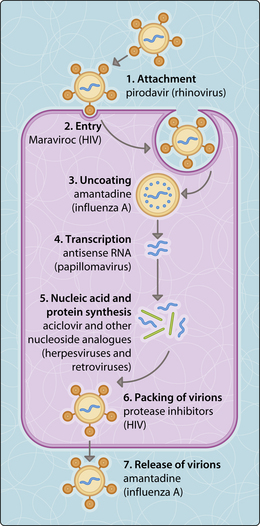

The replication of viruses depends on utilizing the biochemical machinery of the host cell. Drug selectivity is, therefore, harder to achieve than with antibacterial drugs. There are, however, several aspects of the virus replication cycle that can be targeted (Fig. 3.42.1). Optimal therapy depends on rapid diagnosis, and this is particularly difficult when the virus has a long incubation period or prodrome. Latent viruses also prove relatively resistant to antiviral therapy.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue