Anterior Cervical Arthroplasty

Thomas J. Kesman

Bruce V. Darden II

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) has developed into the primary operation for treating symptomatic cervical disc disease over the past several decades (1). While ACDF is reliable at treating the arm pain associated with radiculopathy and the spinal cord compression associated with myelopathy, there are lingering questions regarding the loss of motion and potential adjacent segment degeneration (ASD) over long-term follow-up as a result of the procedure (2,3,5).

Anterior cervical arthroplasty (ACA) was developed with these issues in mind. The goal of ACA is to not only relieve the radiculopathic or myelopathic symptoms but also preserve motion and decrease the likelihood of ASD. Initially, some surgeons had concerns about ongoing motion and potential repetitive microtrauma with the use of arthroplasty in myelopathy; however, studies have shown that patients do no worse with arthroplasty than fusion with single-level myelopathic disease (11).

Indications for ACA are similar to those of ACDF:

Single-level symptomatic cervical disc disease (radiculopathy and/or myelopathy) between C3 and C7 in a skeletally mature patient

Disc herniation, osteophyte formation, and/or loss of disc height on imaging studies

Functional deficit (pain) or neurologic deficit in a distribution consistent with findings on imaging (MRI or CT/CT Myelogram)

Failure of nonoperative treatments for at least 6 weeks in the absence of progressive neurologic deficits

Contraindications for ACA include

Allergy to any component, metal or plastic, appearing in the desired implant

Active local or systemic infection

Osteoporosis with T score <-2.5

Moderate to advanced spondylosis with bridging osteophytes

Disc collapse greater than 50% of its normal height

Absence of motion at desired level of implantation

Marked cervical instability defined by greater than 3 mm of translation on flexion/extension radiographs and/or more than 11 degrees of angulation at the disc space as compared to adjacent levels

Significant kyphotic deformity

Multiple levels requiring treatment

With the above guidelines in mind, it is up to the individual surgeon to determine the appropriate indication for surgery.

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

The most important part of preoperative planning is making an accurate diagnosis. A detailed history and physical exam are essential to planning an appropriate surgery.

The patient should be examined for signs of radiculopathy as exhibited in Table 3-1. Findings consistent with myelopathy including a positive Hoffmann reflex, positive Babinski sign,

spasticity, clonus, gait instability as well as motor weakness, sensory deficits, and bowel and bladder dysfunction should also be noted.

spasticity, clonus, gait instability as well as motor weakness, sensory deficits, and bowel and bladder dysfunction should also be noted.

TABLE 3-1 Radicular Patterns | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

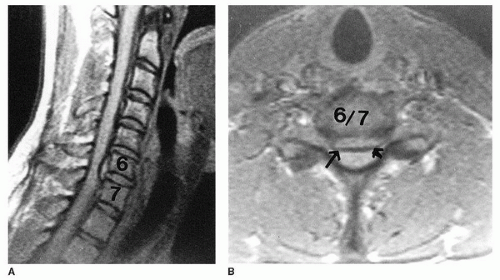

Baseline anteroposterior (AP) and lateral x-rays can be helpful in identifying overall alignment as well as instability or spondylosis. For those patients contemplating a possible surgical intervention, advanced imaging with CT/CT myelogram or MRI is required (Fig. 3-1).

Careful review of diagnostic information including history, physical exam, and electrodiagnostics (as applicable), in conjunction with advanced imaging is key. An appropriate diagnosis and good surgical technique will yield a superior outcome to a technically perfect surgery for the wrong indication.

Once the decision for surgery has been made, further preoperative planning should occur. The surgeon should measure the width and depth of the disc space endplates to allow for appropriate implant sizing. Some companies have templates available to size their proprietary implant.

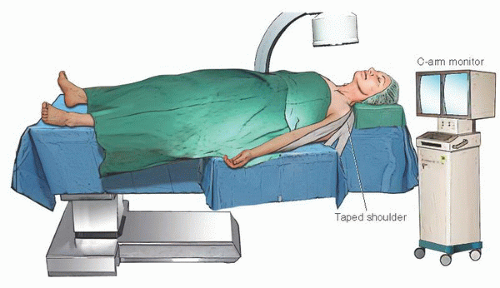

TECHNIQUE

The majority of the initial steps in ACA are similar to ACDF. General endotracheal anesthesia is induced with the endotracheal tube taped in the corner of the mouth away from the approach side of the neck. The patient is transferred supine on the radiolucent portion of an operating table. The radiolucency of the operating table is essential in ACA since both AP and lateral x-rays must be obtained using C-arm fluoroscopy. For those surgeons who prefer intraoperative electrophysiologic monitoring, electrodes can be placed once the patient is transferred to the operating table. Support the natural/neutral position of the neck using a small neck roll or towel beneath the posterior neck and shoulders. The additional support will help to minimize any potential movement during the procedure. The overall position of the head and neck is important, verifying correct neutral position in all planes (flexion/extension, lateral bending, rotation) (Fig. 3-2). An AP fluoroscopic image is obtained at this point to verify that the patient is rotationally neutral. Once the position of the head/ neck has been optimized, the head is secured to the table using a strap or tape. Traction is not recommended as it will provide a distracting force on the neck that may cause the surgeon to oversize the implant.

FIGURE 3-1 MRI images revealing a large central herniated disc at C6-C7 level (arrows) with minimal degeneration at other levels in sagittal (A) and axial (B) images. |

AP and lateral fluoroscopic images should be obtained after securing the head position to verify that the disc space of interest and the respective vertebral bodies are clearly visible on both projections and that the head has not moved. If the shoulders are obscuring the lateral view, traction can be applied to the shoulders using wide tape or other devices to pull the shoulders more distally and out of the view of the lateral image. Any time additional traction is placed on the arms, caution must be exercised to avoid undue pressure on the brachial plexus, especially if the head is already secured.

The patient is then prepped and draped in the usual sterile fashion. Either a standard left-sided approach or right-sided approach is acceptable. We prefer the left-side approach where the anatomy of the recurrent laryngeal nerve is more predictable. The transverse incision, curved in line with Langer’s lines, can be placed via common landmarks (Table 3-2) or by taking a fluoroscopic lateral image with a radiopaque object (Kelly clamp) placed on the skin. Once the incision is localized, the skin is incised with a knife. An insulated monopolar electrocautery is then used to cauterize through the fat to reach the underlying platysma. The platysma is incised with electrocautery in line with the incision. The surgeon then must identify the medial border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and proceed medial to it. The carotid sheath is palpated with a finger to feel the carotid pulse and the sheath retracted laterally. Medially, the esophagus and trachea are pulled across the midline using blunt handheld retractors (Fig. 3-3). The prevertebral fascia and longus colli overlying the anterior cervical spine are identified. Once the anticipated disc level is identified, a small disc marker is inserted into the disc. A lateral radiograph is then taken to verify the appropriate level. The surgeon can adjust proximally or distally as need be to be operating on the correct level disc. Once the correct disc is identified on x-ray, the disc is marked with the electrocautery or knife to remove a small portion of that disc. If crossing vessels are encountered (superior or inferior thyroid), they may be cauterized carefully using bipolar electrocautery and divided.

The above procedure is universal to all major cervical disc arthroplasties in the United States. Below we will describe the procedure for the Synthes ProDisc-C (Synthes USA, Inc., West Chester, PA) implant as an example (10) (Fig. 3-4), but other popular arthroplasty devices such as the BRYAN Cervical Disc System (Fig. 3-5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree