Cervical Vertebrectomy and Plating

William Ryan Spiker

Darrel S. Brodke

INDICATIONS

Cervical vertebrectomy (also known as corpectomy) and plating is indicated for patients with anterior compression of the cervical spinal cord and exiting cervical nerve roots. It is an alternative to multiple level discectomy and interbody fusion and is uniquely well suited to relieve cord compression occurring not only at the disc level but also behind the vertebral bodies (e.g., disc herniation fragment). Common indications for vertebrectomy and plating of the cervical spine include degenerative cervical spondylotic myelopathy (without hyperlordosis), traumatic fractures and dislocations, congenital cervical stenosis, ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL), tumors, and infections.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Anterior cervical exposures should not be attempted in the face of severe anterior neck trauma with tracheal or esophageal injury that precludes safe access to the spine. Similarly, careful consideration is necessary when placing hardware in the infected patient. Anterior surgery should be avoided when in the setting of posterior sources of neural compression such as hyperlordosis or ligamentous infolding. Diminished bone quality from osteoporosis or metastatic disease may lead to graft failure, subsidence, migration, or kyphotic collapse. Relative contraindications that carry increased risk of complications include poor nutrition (albumin and prealbumin levels), bleeding disorder, aberrant vertebral artery anatomy, smoking, history of previous nonunion, advanced age, and inability to follow postoperative activity restrictions. Additionally, anterior corpectomy of more than two vertebral bodies with a strut graft (with or without plate) has a high nonunion rate with increased risk of graft or plate dislodgement and often necessitates additional posterior stabilization (9).

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

History and Physical

As always, preoperative preparation begins with an accurate and thorough history and physical examination.

Key historical facts include duration, severity and timing of symptoms, symptoms of myelopathy/ radiculopathy, exacerbating and mitigating factors, and results of previous treatments.

Key physical examination findings include inspection of cervical alignment (lordosis vs kyphosis), evaluation for anterior neck scars, upper extremity examination to rule out peripheral causes of symptoms, cervical spine range of motion, and detailed neurovascular exam of upper and lower extremities including strength, sensation, reflexes, and assessment of long-tract signs.

Patient Education

Patients should be extensively counseled regarding the goals of surgery and the specific risks of surgical intervention. Managing postoperative infections, persistent pain, numbness or weakness, decreased range of motion, and other complications are made easier when these topics have been broached preoperatively.

Radiology

Radiographic evaluation begins with plain radiographs, including flexion and extension views and a long spine film in patients with a deformity on examination or initial radiographic views. MRI provides excellent visualization of the soft tissues, including the spinal cord and exiting nerve roots. The course of the vertebral arteries should be confirmed on every preoperative MRI to minimize risk of intraoperative injury. In cases with severe deformity, tumor resection, or difficult revisions, angiography can be used to more clearly understand the course of the vertebral arteries and their branches. Preoperative occlusion of the artery may be beneficial in specific patients. CT myelography can also be used to identify neural structure impingement with the advantage of improved visualization of bony structures (important in OPLL) and decreased scatter from previously placed hardware.

Graft Choices

Preoperative planning for vertebrectomy includes determination of the size and type of bone graft to be used for anterior column reconstruction. Autologous iliac crest bone graft is an option for one or sometimes two-level vertebral body resections, while auto or allograft fibula grafts are usually preferred for larger reconstructions. Consideration for supplemental posterior fixation is important in three-level vertebrectomies and high-risk patients (history of smoking, osteoporosis, kyphotic deformity, etc.) to minimize risk of pseudarthrosis. Due to the high union rates in circumferential (anterior and posterior) fusions, allograft is often used for anterior column support in these cases.

An alternative to allograft bone for anterior column support after vertebrectomy is the placement of a cage or spacer made of titanium, ceramic, carbon fiber, or poly-ether-ether-ketone (PEEK). These have the advantage of strength and easy of placement, while potentially adding significant cost to the case.

TECHNIQUE

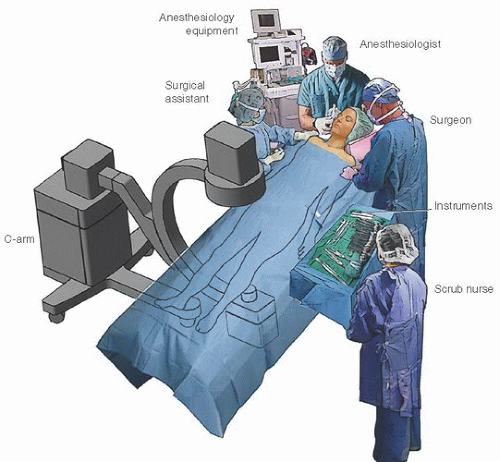

(Fig. 4-1)

Large fluoroscope—off of the upper right hand corner of the OR table

Surgical microscope—off of the lower right hand corner of the OR table

High-speed air drill—at foot of OR table—opposite of scrub tech

Skin preparation: chlorhexidine (+/- alcohol pre-prep)

+/- Loupe versus microscope

Positioning

Know preoperative cervical range of motion—discuss possible nasotracheal/fiberoptic intubation if poor range of motion

Discuss role of total IV anesthesia to allow measurement of somatosensory and motor evoked potentials.

Supine position, arms tucked to side

Head straight or rotated slightly away from side of surgical approach

Pad between scapula to obtain desired extension. Care must be taken to avoid hyperextension in the myelopathic patient.

Wide cloth tape can be used to pull down on the shoulders to increase fluoroscopic visualization of the caudal cervical spine (C6-T1). Care should be taken to avoid overly aggressive retraction and brachial plexus injury

Mark desired level of incision with fluoroscopic guidance prior to skin preparation

Traction

Intraoperative traction to stabilize spine during vertebrectomy is particularly important in patients with myelopathy and unstable fractures. This may also limit Ligamentum Flavum infolding and cord compression with positioning.

Head halter traction can be used for single-level resections

Gardner-Wells tongs can be used with single- or multilevel resections

Halo ring traction can be used if the patient is going to be in halo-vest immobilization postoperatively (attach the vest at the conclusion of surgery)

10 to 15 pounds of traction is used to stabilize the spine, can be increased as necessary during placement of the graft

Graft Harvest

Iliac crest: small bump under crest

Fibular autograft: bump under ipsilateral hip, thigh tourniquet

Approach

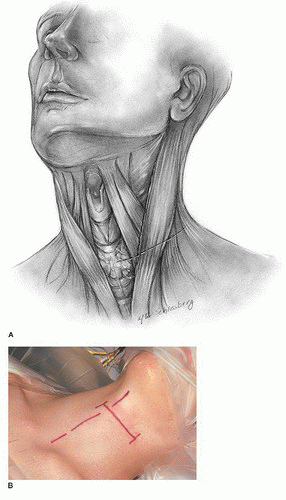

Incision (Fig. 4-2)

Historically, left-sided approach is preferred for the lower cervical spine due to more predictable course of the recurrent laryngeal nerve. However, the side of approach is often chosen contralateral to the decompression (if one side is worse than the other) to ease deep access and visualization.

Revision cases: important to note function of recurrent laryngeal nerves

Approach from the same side as prior surgery, laryngoscopy optional

Approach from the contralateral side, direct laryngoscopy and vocal cord visualization should be performed to rule out unilateral (potentially asymptomatic) vocal cord paralysis preoperatively.

If laryngoscopy reveals normal vocal cord motion—contralateral approach allows dissection through native tissue and likely less risk of trachea, esophagus, and neurovascular injury

If laryngoscopy reveals abnormal vocal cord motion—approach through previous surgical incision to avoid risk of bilateral nerve injuries

Transverse incision allows exposure for up to four-level vertebrectomy and provides a significantly better cosmetic result

Longitudinal incision just anterior to the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) is rarely needed, but does allow a more extensile exposure if required, at the cost of a significantly worse cosmetic result

Anatomic landmarks for incision: (see Table 4-1)

Use preoperative imaging to confirm correlation of landmarks and levels

TABLE 4-1 Superficial Anatomic Landmarks of the Cervical Spine | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

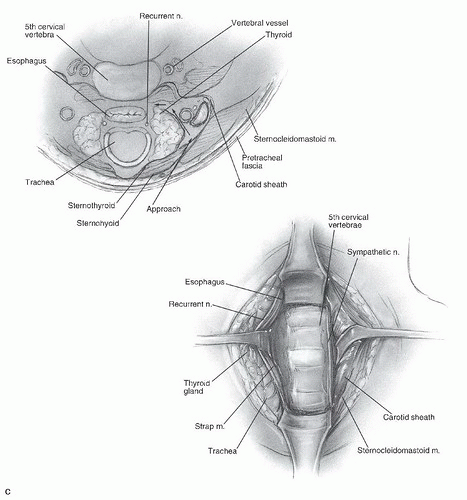

Dissection (Figs. 4-3 and 4-4)

Platysma can be incised horizontally or vertically

We incise horizontally along the length of the wound, after bluntly dissecting it from deep structures, without preplatysmal dissection, which improves wound closure.

Underlying superficial cervical fascia can be separated off of the deeper SCM and anterior jugular vein with Metzenbaum scissors, usually bluntly

Vein can be ligated with suture if necessary, but is usually retracted

Cranial and caudal subplatysmal release of anterior cervical fascia is key to a wide exposure

SCM is retracted laterally, and the omohyoid is often seen traversing the field

Carotid sheath is palpated with index finger (contents = carotid artery, internal jugular vein, and vagus nerve)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree