Anterior Cervical Approach

Sanford E. Emery

Since the 1950s, the anterior approach to the cervical spine has become the approach of choice for many operative procedures performed today. Much of the pathoanatomy necessitating surgery is located in the anterior column of the spine, which lends itself to the direct anterior approach in treating degenerative, traumatic, neoplastic, infectious, and deformity conditions. Knowledge of the anatomy and respecting tissue planes allows the spine surgeon anterior access from C1 to the cervicothoracic junction. We will review the approach to the midcervical spine since it is by far the most common approach utilized, followed by the less common techniques for the upper cervical spine and the cervicothoracic junction.

ANTERIOR APPROACH TO THE CERVICAL SPINE (C3-C7)

Indications/Contraindications

The goals of most operative spine procedures are decompression of the spinal canal, arthrodesis, or both. Because much of the pathology requiring operative intervention involves the disc space or vertebral bodies, the anterior approach is indicated for many disorders using decompression and fusion techniques. Disc herniations or spondylosis changes with cord or root compression are easily accessed from the anterior approach. Larger procedures such as cervical corpectomies to decompress longer areas of the spinal canal or to correct deformity will require the anterior approach in most instances. Reconstruction of the anterior column following fractures, neoplasms, or severe infections utilizes the same operative approach.

Contraindications to the anterior approach are uncommon. Multiple prior anterior surgeries, skin changes from radiation, or at times, severe obesity may lead the surgeon to opt for posterior approach options to treat certain conditions. It should be noted that in patients with prior anterior approaches, any suspicion of a recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) palsy with unilateral vocal cord paralysis should be identified before other anterior procedures are performed, since the uninjured side should not be used so as to avoid potential bilateral vocal cord paralysis.

Preoperative Preparation

In preparing for an anterior operative procedure, the surgeon should palpate the skin and soft tissues of the patient’s neck looking for an enlarged thyroid gland that could be problematic for exposure of the lower cervical spine. Some retraction on the carotid arteries during the anterior approach is unavoidable, so patients with known or suspected carotid artery disease should be evaluated preoperatively, though in this author’s opinion the risk of neurologic sequelae from retraction of the carotid artery is extremely rare. Identification of an existing unilateral vocal cord paralysis is mentioned above and would dictate approaching the spine anteriorly from the same side as the injured RLN so as not to create a bilateral injury and thus an inability to protect the airway.

The course of the vertebral artery should be checked preoperatively using routine magnetic resonance imaging or occasionally computed tomography angiography or magnetic resonance angiography. Aberrant medialization of vertebral arteries is uncommon though well described (5) and creates a high risk for vertebral artery injury in even routine cases.

Technique

Positioning of the patient for the anterior approach is important in facilitating exposure of the spine. For patients without severe cord compression, a roll can be placed between the shoulder blades allowing for neck extension and retraction of the shoulders. A general-use radiolucent table with a rectangular extension will allow raising or lowering of the head into more or less extension as needed during the case such as to compress the bone graft before plating. For discectomy and one-level corpectomy procedures, traction is not needed since screw-post-type retractors can easily distract discs or one-level corpectomy distances. For two or more level corpectomy procedures, intraoperative traction can be helpful. Both neck extension and the amount of weights must be used with extreme care or not at all in patients with spinal cord compression so as not to create spinal cord injury. Taping down of the shoulders or using wrist restraints with light traction can help with fluoroscopic or radiographic visualization of the lower cervical spine. Over pulling should be avoided so as not to create a brachial plexus injury. Rotation of the head 10 to 15 degrees away from the side of the operative approach will help with exposure.

The superficial anatomy enables placement of a transverse incision at the appropriate level for the indicated procedure. The hyoid bone is at C3, the thyroid cartilage at C4 and C5, and the cricoid cartilage is at C6. The carotid tubercle is often palpable as a prominence of the transverse process of C6. Practically speaking, an incision for a C5-C6 discectomy and fusion procedure is typically three finger breadths above the clavicle and two finger breadths for a C6-C7 level. Fluoroscopic or radiographic confirmation intraoperatively is, of course, required to ensure the appropriate level. The typical sizing of the transverse incision starts approximately a centimeter on the other side of midline coming over to just past the border of the sternocleidomastoid on the surgeon’s side. Cephalad and caudad incision of the fascial planes will allow for easy retraction and a surprisingly extensile approach over many vertebral levels. A longitudinal incision can be made along the border of the sternocleidomastoid for a more extensile approach, though it is much less cosmetic and rarely required. Two transverse incisions at distinct levels for long reconstruction constructs is also an option.

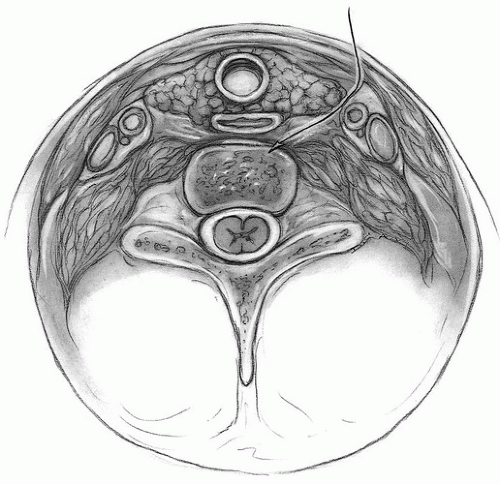

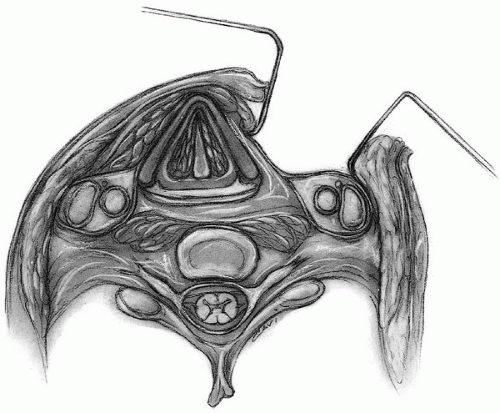

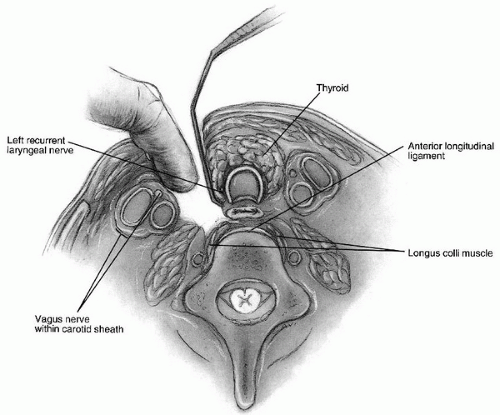

After appropriate prepping and draping, the skin incision is made transversely at the chosen level for the classic Smith-Robinson anterior approach to the midcervical spine (24) (Fig. 1-1). Skin and subcutaneous tissue are incised with a knife blade, and any bleeding is controlled with cautery. Below the subcutaneous tissue is the platysma with vertical fibers. This author divides the platysma sharply the length of the incision, although it can be split vertically and retracted. There is a thin superficial cervical fascial layer that is incised transversely. This layer usually exposes branches of the external jugular system, which at times can be large. Tying and dividing these branches is sometimes prudent, although often they can simply be retracted with the deeper tissues. At this point, the deep cervical fascial layer is incised superiorly and inferiorly just medial to the border of the sternocleidomastoid (Fig. 1-2). This layer is the fascia that envelops the sternocleidomastoid and continues medially to envelop the strap muscles (10). Identifying and incising this fascial layer allows for extensile retraction up and down the anterior spine. The carotid artery is then palpated with an index finger and held laterally (Fig. 1-3). An appendicial-type retractor is placed medial to the surgeon’s index finger deeply and retracts the trachea and esophagus medially. This retraction allows for a combination of blunt and sharp dissection of the pretracheal or alar fascia, which overlies the prevertebral fascia. At this point, the discs and vertebral bodies should be easily palpable and visible. The prevertebral fascia (11) can be lifted with forceps and dissected with a pair of Metzenbaum scissors to expose the anterior longitudinal ligament, discs, and vertebral bodies. A peanut-type dissector is useful for sweeping away the thin fascial layers off of the spine superiorly and inferiorly, and the deep retractors can be placed. The longus colli muscles run along each side of the spine and will actually converge toward the tubercle of C1 if the exposure is extended cephalad. The medial border of the longus colli along each side is typically elevated for 3 to 4 mm using cautery. This dissection allows deep retractor blades to grip better and minimizes dislodgement of the retractors. Overzealous elevation of longus colli could threaten the vertebral arteries, however, and should be avoided.

Self-retaining retractors have been used for many years for anterior cervical procedures and, with careful use, are very safe. Handheld retractors are possibly easier on the esophagus since the retraction will inherently be more intermittent, but this method requires more personnel. After the surgery, the wound is irrigated and the retractors removed. Many surgeons use a small drain that is brought out through the incision without making a cosmetically unacceptable separate stab wound. The platysma is the first layer closed with 3-0 Vicryl followed by 4-0 Vicryl in the subcutaneous layer and often a subcuticular Prolene or Vicryl layer for cosmetic skin closure.

Postoperative Management

Elevating the patient’s head of the bed approximately 30 to 40 degrees may mitigate postoperative swelling. Most patients undergoing the common anterior cervical procedures can be extubated immediately after surgery. Larger multilevel corpectomy cases or more complex conditions such as tumors or deformity corrections may warrant a delayed extubation primarily to monitor airway edema (8). There is very little tension on the anterior cervical tissues, and typically the skin sutures can be removed in days rather than weeks.

Complications

Complications encountered in the anterior approach to the cervical spine are typically based on anatomy unique to this region. Dysphagia (swallowing difficulty) is nearly universal in the first few days after surgery in these patients, presumably due to retraction of the esophagus. This complication recovers quickly in most patients although better investigation of dysphagia in recent years has documented a higher increase at 6 months and even at 12 months than was previously appreciated (3,15,22). Injury to the esophageal wall with perforation can also occur and, if unrecognized, can

lead to a life-threatening postoperative mediastinitis. Intraoperative indigo carmine can be injected by the anesthesiologist into the esophagus via a nasogastric tube to try and detect any perforations though this technique has not been proven to be reliable. If any are noted, then otolaryngologic or thoracic consultation is recommended for closure and no oral intake is allowed for a period postoperatively to allow the injury to seal over.

lead to a life-threatening postoperative mediastinitis. Intraoperative indigo carmine can be injected by the anesthesiologist into the esophagus via a nasogastric tube to try and detect any perforations though this technique has not been proven to be reliable. If any are noted, then otolaryngologic or thoracic consultation is recommended for closure and no oral intake is allowed for a period postoperatively to allow the injury to seal over.

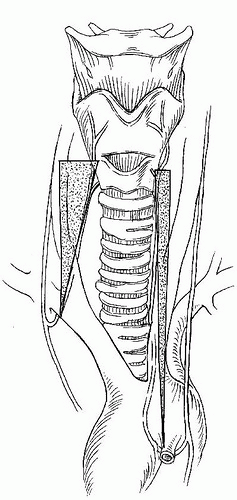

Dysphonia (hoarseness or voice changes) can arise from injury to either the RLN or the superior laryngeal nerve. The RLN supplies all the intrinsic muscles of the larynx with the exception of cricothyroid, which is supplied by the superior laryngeal nerve. An RLN palsy leaves the vocal cord in an open or semiopen position on that side, causing difficulty with phonation and even protection of the airway. The left RLN branches off the vagus and loops under the arch of the aorta and returns cephalad in the tracheal esophageal groove up to the larynx. The path of the right RLN is slightly more variable (Fig. 1-4). It loops under the right subclavian artery and travels up to the larynx with a slightly less predictable course. Rarely, the nerve will descend directly into the larynx without looping as a recurrent structure (21). Because of these anatomic findings, some surgeons prefer a left-sided approach believing it will decrease the incidence of RLN injury. This opinion has been difficult to prove in the literature with any statistical validity (4), however, and both right-sided and left-sided approaches are commonly utilized. Suggested techniques to decrease RLN palsy such as deflating and reinflating the endotracheal tube cuff, which may allow the tube to adjust itself within the larynx after the retractors are placed, is believed to be effective by some authors and not by others (1,2). Most recurrent nerve palsies recover over time, but can take up to a year postoperatively (29). Typically, the superior laryngeal nerve is at risk for exposure at the C3-C4 level. Small traversing nerves should be protected and retracted rather than simply transected. Superior laryngeal nerve injury results in weak phonation and voice fatigue, which can be a major disability for singing.

Vertebral artery injury, though more at risk during discectomy or corpectomy procedures, can be injured during the approach as well. As mentioned above, preoperative identification of aberrant vertebral arteries is important to avoid an artery looping more medially under the longus colli. Though possible, injury of the carotid artery is notably rare in anterior approaches to the cervical spine.

Horner syndrome has been described as a complication of the anterior approach. This complication results from an injury to the sympathetic plexus that descends lateral to the longus colli muscle on each side. The sympathetic plexus courses more medially near the carotid tubercle at C6. Clinical features of Horner syndrome are ptosis (drooping eyelid), miosis (pupillary constriction), and anhidrosis (dry eye) (7).

TRANSORAL APPROACH TO THE UPPER CERVICAL SPINE

Indications/Contraindications

This operative approach allows direct visualization of the anterior arch of C1 and the body of C2. It is used for removal of the odontoid and pannus in rheumatoid arthritis patients when indicated, for debridement of infection, and decompression for tumor. Because the incision is transmucosal in the posterior pharynx, there is theoretically a higher infection rate with this approach given oralpharyngeal flora. Thus the most common indications for transoral approaches are for debridement or decompression and more limited for bone graft reconstruction or instrumentation. Other authors have described a tongue and mandible splitting technique for a more extensile approach (25

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree