Chapter 13 Ankle Sprains, Ankle Instability, and Syndesmosis Injuries

Introduction

Because it generally is agreed that most acute lateral ankle sprains can be treated nonoperatively while acknowledging an incidence of late problems in 10% to 20% it is no surprise that lateral ankle ligament reconstruction is commonplace.1 This approach to the treatment of lateral ankle sprains is reasonable only if reconstructive procedures for the lateral ankle ligaments can be as successful as primary repair. Recent consensus of orthopaedic opinion supports this viewpoint. However, there is still controversy that persists regarding the best method of treatment of acute lateral ankle sprains because of the paucity of scientific studies in this field that meet the requirements for proof of method in outcomes-based research.2

Most patients with chronic lateral ankle sprains and instability present with either recurrent ankle sprains after an initial acute sprain or with the feeling of looseness in the ankle and the sensation of “giving way.” These patients may complain of ankle pain, but it is not a prerequisite feature of this problem, although the examination confirms the presence of a positive anterior drawer test and/or a positive inversion stress test. Tenderness may be present, but often is more indicative of associated pathology, as noted later. The examiner must be thorough enough to rule out other sources of symptoms (Table 13-1) because the clinical diagnosis of chronic lateral ankle instability has been associated with the intraoperative findings of peroneal tendon pathology (tenosynovitis, tears, dislocation), anterolateral impingement lesions, ankle synovitis, intraarticular loose bodies, talar osteochondral lesions, and medial ankle tenosynovitis.3 A comprehensive physical therapy program should be initiated first. Symptoms often will resolve with correction of the deficits in proprioception, strength, and flexibility. Regardless, therapy can improve the results in patients who ultimately require surgery. The nonoperative treatment also includes activity and/or shoe modification (e.g., lateral heel wedge), an ankle-foot orthosis, and/or orthotic devices incorporating a lateral heel wedge. Brostrom4 found that symptoms of instability remained in 20% of his patients who were treated in a conservative fashion. Athletes may use a nonoperative approach to get through a season but rarely consider this an acceptable long-term solution unless their symptoms are minimal.

Table 13-1 Sources of Chronic Pain or Instability after Ankle Sprain

| Articular injury | Impingement |

| Chondral fractures | Anterior tibial osteophyte |

| Osteochondral fractures | Anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament |

| Nerve injury | Miscellaneous conditions |

| Superficial peroneal | Failure to regain normal motion (tight Achilles) |

| Posterior tibial | Proprioceptive deficits |

| Sural | Tarsal coalition |

| Tendon injury | Meniscoid lesions |

| Peroneal tendon (tear or dislocation) | Accessory soleus muscle |

| Posterior tibial tendon | Unrelated ongoing pathology masked by routine sprain |

| Other ligamentous injury | Unsuspected rheumatologic condition |

| Syndesmosis | Occult tumor |

| Subtalar | Chronic ligamentous laxity (collagen disease) |

| Bifurcate | Neuromuscular disease (Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease) |

| Calcaneocuboid | Neurologic disorders (L5 radiculopathy, poststroke ) |

Surgical Treatment

Diagnostic and surgical arthroscopy is warranted before ankle stabilization. Chondral injury is the most common problem discovered at arthroscopy, with almost 30% of acute ankle injuries and 95% of chronic ankles having this lesion in one study of an athletic population.5 A more recent study by Komenda and Ferkel6 found only a 25% incidence of chondral injury in their chronic ankle instability series. Regardless, the value of ankle arthroscopy, particularly in cases of chondral fracture, loose bodies, and soft-tissue impingement has been confirmed in several studies.6–9 Hintermann and co-workers9 concluded that essential information was obtained by performing ankle arthroscopy at the time of surgery for ankle instability.

Operations for stabilization of the lateral ankle in cases of chronic instability are numerous. When instability persists despite conservative treatment, the surgeon can choose from more than 50 methods of reconstructing the lateral ankle ligaments. Fortunately, the reported short-term success rate is greater than 80% for all these procedures, according to the literature.10 The primary difference in the various procedures is whether or not they are designed to anatomically reconstruct the ligaments. In a manner reminiscent of the surgical history of shoulder and knee instability, more anatomic reconstructions are gaining popularity for ankle instability. This began with the introduction of the secondary repair of the previously injured ligaments by Lennart Brostrom in 1966.11 It has taken almost four decades for the accumulation of scientific evidence to cast doubt on the tenodesis procedures described by Evans, Watson-Jones, Larsen, and Chrisman and Snook.12–16 The following discussion focuses on the anatomic procedures, whether by direct repair in the tradition of Brostrom or by the use of tissue transfer or tissue grafts done through anatomically placed bone tunnels.

Brostrom described his anatomic repair as a delayed procedure for chronic lateral ankle instability. The procedure is a straightforward division and imbrication of the anterior talofibular ligament. The calcaneofibular ligament is not addressed. Various modifications have been described, the most popular being a reinsertion into a bony trough,17 imbrication of the calcaneofibular ligament,18 and reinforcement with the inferior extensor retinaculum.19 Other authors have described the use of different graft sources to rebuild the lateral ankle ligaments while emphasizing the anatomic placement of bone tunnels. Graft sources for this include the plantaris tendon,20–22 the split peroneus brevis tendon,23,24 hamstring tendons,25–27 and allograft tendons.28,29

Results

Results of the Brostrom anatomic reconstruction are excellent. In Brostrom’s original study, 51 of 60 patients demonstrated minimal or no instability at follow-up.11 Other reported results from the Brostrom procedure or a modification thereof include large and small series of patients from around the world, with more than 500 cases reported and results ranging from 85% to 100% successful.13,30–37 Lesser results are associated with heel varus, inadequate rehabilitation, nerve injury, preexisting arthritis, and significant repeat sprains.

Objective results of comparison studies that include anatomic procedures such as the Brostrom versus tenodesis procedures all favor the former procedure. In a cadaveric study comparing the Chrisman-Snook, Watson-Jones, and modified Brostrom procedures, the modified Brostrom procedure produced the least amount of talar tilt and anterior drawer translation, as well as having the greatest mechanical strength.38 Another study, a prospective, randomized comparison of Chrisman-Snook and modified Brostrom, found that both procedures had greater than 80% good or excellent results, but there were more complications in the Chrisman-Snook group (five with wound problems, eight with sural nerve injury, and six with the feeling that the ankle was “too tight”). Brostrom complications were almost nonexistent and included no wound problems, no nerve injury, and only two with a feeling that the ankle was “too tight.”13 In a long-term, multicenter outcome study of anatomic reconstruction versus teno-desis, Krips and associates39 found that more patients with tenodesis procedures had positive anterior drawer signs, medial ankle degenerative changes, higher mean talar tilt, and anterior talar translation. In addition, significantly fewer patients in the tenodesis group had excellent results, and more patients had a fair or poor result. In a follow-up study, patients who underwent tenodesis procedures underwent more revision procedures, demonstrated more osteoarthritis, more instability, tenderness, chronic pain, and limited dorsiflexion. Good to excellent results were found in 80% of patients at 30-year follow-up after anatomic reconstruction, versus only 33% after Evans tenodesis.40 Overall, it appears that tenodesis procedures fail to restore the normal anatomy, resulting in lessened mechanical stability and a decrease in patient satisfaction. Because of these well-documented inherent problems of nonanatomic tenodesis procedures, anatomic ligamentous reconstruction is the preferable treatment approach in almost all circumstances.

Complications

Neurologic damage and wound complications are not infrequent. Injury to the superficial nerves is the most common complication following operative repair of the lateral ankle ligaments. Depending on the report and the type of surgical approach used, the incidence ranges from 7% to 19%.41 The sural nerve is at greater risk with tenodesis procedures.42 Wound dehiscence, superficial and deep infection, loss of ankle and/or subtalar motion, and deep venous thrombosis are less-often reported complications. Wise patient selection and good surgical technique are paramount in keeping these complications to a minimum.

Direct Ligament Repair (Modified Brostrom Procedure)

For most cases of chronic lateral ankle instability in the athletic population, a modified Brostrom technique is applicable. Its advantage is that it is an anatomic repair, with no tenodesis effect and no major change in the ankle and subtalar joint biomechanics. A second advantage is that it does not sacrifice adjacent healthy tissue. Indications include those patients with chronic lateral ankle ligament instability who are unresponsive to physical therapy. Contraindications include patients with structural varus deformities, previously failed lateral ligament reconstructions, genetic collagen disorders (Marfan’s and Ehlers-Danlos syndromes), or posttraumatic conditions with soft-tissue loss. Relative contraindications are obese patients (more than 250 lb) or patients whose instability exceeds 10 years duration with history of multiple severe sprains.17 For these patients, consideration is given to use a free tendon graft (allograft or autograft) for augmentation.

Technique

Figure 13-2 Stretched anterior lateral ligaments found in typical chronic ankle sprains.

Courtesy Matthew Morrey, MD.

Figure 13-3 Imbrication of stretched ligaments in anatomical reconstructive procedure.

Courtesy Matthew Morrey, MD.

Figure 13-4 Bony trough used for attachment of anterior talofibular and calcaneofibular ligaments to bone.

Courtesy Matthew Morrey, MD.

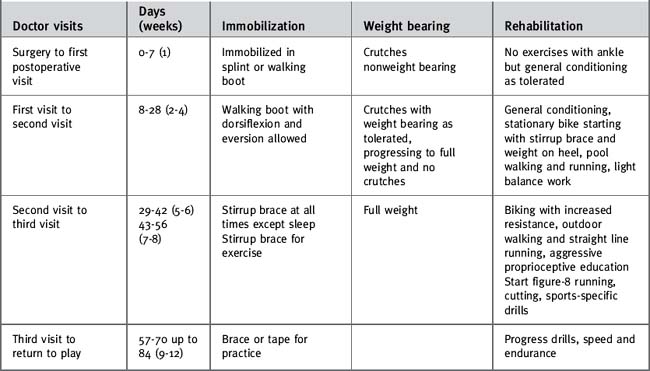

Postoperative care

For nonathletes, a 10- to 12-week period of protection is warranted, the first 4 to 6 weeks with the patient being in a cast or walking boot with limited exercise and the second 6 weeks with the patient being in a removable brace or walking boot when a more aggressive rehabilitation program is begun. Resumption of vigorous exercise or recreational sports generally takes longer in this population. Although I believe in individualizing the rehabilitation program to the patient and the pathology, a table is provided as a general guideline (Table 13-2).

Failed Lateral Ankle Ligament Reconstruction

Of patients who undergo a lateral ankle reconstruction, 5% to 15% may proceed to failure, requiring further intervention. Perhaps the most common cause for failure is recurrent instability. The primary surgical procedure may have been inadequate, the patient may have reinjured the ankle, or there may have been inherent factors that predisposed a patient to failure (benign joint hypermobility syndrome, Marfan’s syndrome, or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome).42 The patient often describes a loose feeling in the ankle or the sensation of “giving way” or “turning easily.” Another cause of failure in lateral ankle reconstruction is chronic pain, constant or only during activity, resulting from intra-articular pathology or postoperative stiffness.

Treatment

The lateral ankle is exposed through one of two incisions chosen on the basis of the underlying pathology. When the pathology is limited to the previously reconstructed lateral ligamentous complex, a small, curvilinear incision paralleling the anterior and distal border of the fibula is used, similar to the incision for the previously described Brostrom procedure (see Fig. 13-1). For cases with more extensive pathology (peroneal tendon tears or anterior osteophytes), a longitudinal incision is made over the posterior border of the fibula, curving distally to the sinus tarsi and the anterior process of the calcaneus. With both approaches, the ankle joint is exposed and the anterolateral capsule is divided, preserving as much potentially useful tissue as possible.

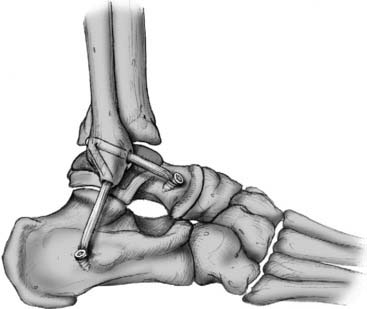

While holding the ankle in neutral dorsiflexion and neutral inversion/eversion, the surgeon applies tension to the graft. A bioabsorbable screw is placed with an interference fit in the calcaneal bone tunnel to secure the graft (Fig. 13-7). Alternatively, the Arthrex Biotenodesis System can be used to insert the tendon in the bone tunnel and fixate the graft with the bioabsorbable screw. Once the graft is secured and the tension is judged to be adequate, the ankle is tested for stability and range of motion, and stress radiographs are performed under fluoroscopy. If the ankle is still unstable, the screw in the calcaneus is removed, the graft further tensioned, and the screw replaced with the heel in slight eversion. The graft is secured to the periosteum of the fibula at the entrance and exit holes with absorbable suture. The inferior extensor retinaculum or other local tissue can be used for augmentation if further stability is required.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree