Anatomy of the Hip

Raymond H. Kim and Douglas A. Dennis

Key Points

Introduction

Although commonly referred to as a “simple ball-and-socket joint,” the hip is a beautifully architectured joint that is worthy of appreciation for its form and function. Knowledge of hip anatomy is critical to perform surgical approaches and to avoid potential complications. This chapter describes the surface anatomy, the osseous anatomy, the musculature, the vasculature, and the neuroanatomy as they pertain to the hip surgeon.

Surface Anatomy

The superficial landmarks are clinically relevant for describing areas of pain on physical examination and are surgically significant for determining incision placement.

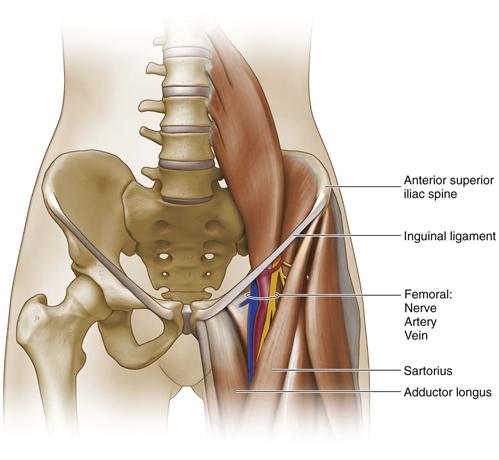

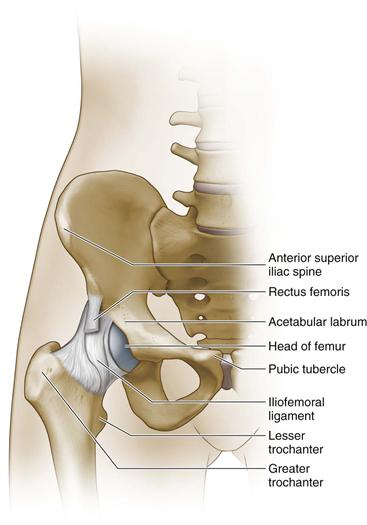

Anteriorly, the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) is easily palpable and represents the anterior prominence of the iliac crest (Fig. 15-1). The sartorius and the tensor fascia lata rely on the ASIS for their proximal attachments. At the anterior midline of the pelvis, the pubic symphysis is buttressed by the pubic tubercles, which represent the medial ends of the superior pubic rami. The ASIS and the pubic symphysis define the coronal plane of the pelvis. The ASIS and the pubic tubercle are bridged by the inguinal ligament. The femoral artery can be palpated midway between the ASIS and the pubic tubercle, just distal to the inguinal ligament.

Figure 15-1 The anterior superior iliac spine represents the anterior prominence of the iliac crest. The femoral triangle is bordered superiorly by the inguinal ligament, laterally by the sartorius, and medially by the adductor longus, and the floor by the iliopsoas, the pectineus, and the adductor brevis. Within the triangle, the artery is positioned adjacent to the femoral nerve laterally and the femoral vein medially.

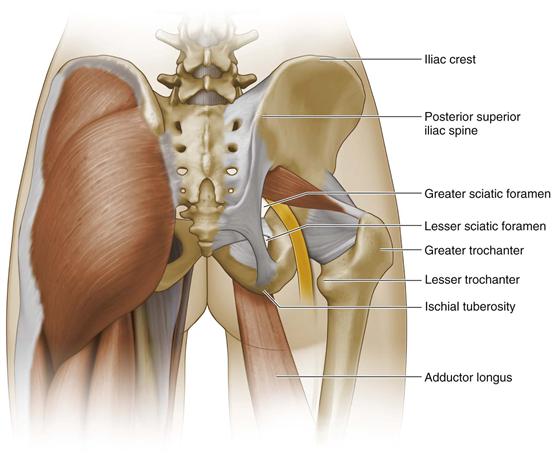

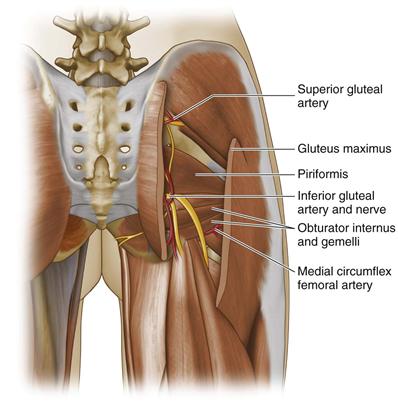

Laterally, the iliac crest can be traced from the ASIS arching posteriorly, and it ends posteriorly at the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS). The greater trochanter is an easily palpable lateral prominence that serves as the muscular insertion for the gluteus medius and minimus laterally and the piriformis, obturator internus, and gemelli medially; the trochanteric ridge distally serves as the origin for the vastus lateralis.

Posteriorly, the PSIS is easily palpable and provides part of the origin of the gluteus maximus, as well as the posterior sacroiliac ligaments (Fig. 15-2). The PSIS is often identifiable by a characteristic dimpling of the skin. Inferior to the lower border of the gluteus maximus, the ischial tuberosity can be palpated.

Figure 15-2 The posterior superior iliac spine provides part of the origin of the gluteus maximus and the posterior sacroiliac ligaments.

Osseous and Ligamentous Anatomy

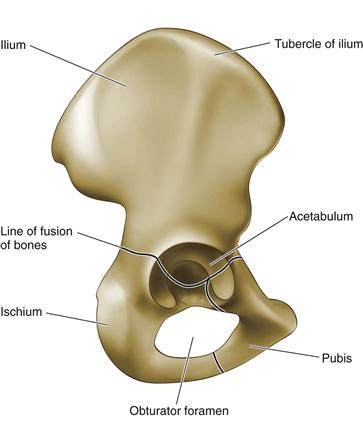

The hemipelvis comprises the ilium, the ischium, and the pubis, which developmentally unite after fusion of the triradiate cartilage within the acetabulum (Fig. 15-3). The ilium is the superior flattened portion of the pelvis with the superficial anatomy described previously. The greater sciatic notch is a major landmark on the ilium and is located posterior and superior to the acetabulum. The ischium is an L-shaped bone that comprises the inferior portion of the pelvis. The pubis is composed of a body and a superior and inferior ramus. The rami in conjunction with the ischium form a window called the obturator foramen. The bodies of the pubis articulate at the midline anteriorly at the pubic symphysis.

Figure 15-3 The hemipelvis comprises the ilium, the ischium, and the pubis.

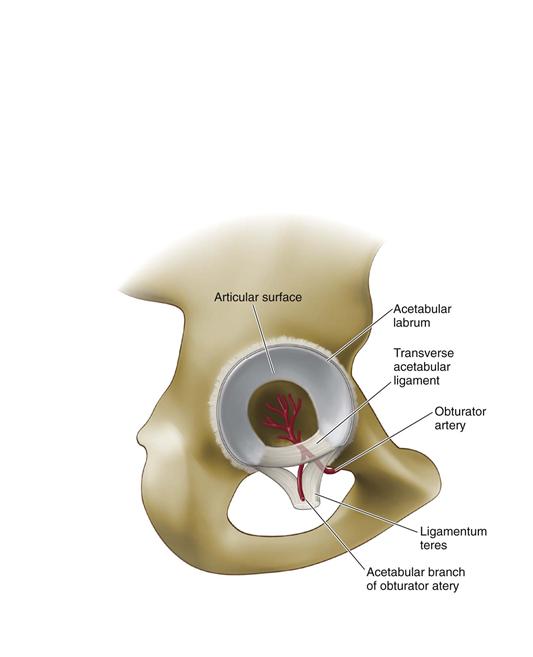

The acetabulum consists of a lunate-shaped articular region of hyaline cartilage and a central nonarticular fossa (Fig. 15-4). From the inferior aspect of the fossa, the ligamentum teres carries the acetabular branches of the posterior division of the obturator vessels over to the fovea capitis, which is a small depression on the medial aspect of the femoral head. The acetabulum is deepened by the labrum, a fibrocartilaginous rim, which becomes the transverse acetabular ligament inferiorly as it bridges the cotyloid notch.

Figure 15-4 The acetabulum consists of a lunate-shaped articular region of hyaline cartilage and a central nonarticular fossa. From the inferior aspect of the fossa, the ligamentum teres carries the acetabular branches of the posterior division of the obturator vessels.

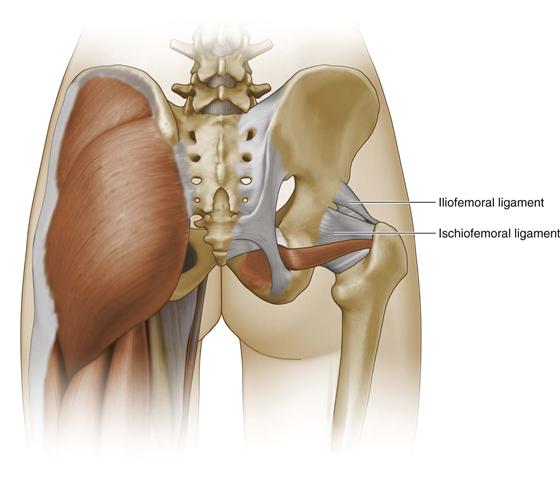

The acetabulum articulates with the femoral head in a ball-and-socket configuration and allows a wide range of motion. The joint is circumferentially enclosed by the hip capsule, which attaches to the labrum medially. Intimately associated with the capsule are ligaments, which also surround the hip joint. Anteriorly, the hip joint is covered by an inverted Y–shaped iliofemoral ligament and by the pubofemoral ligament (Fig. 15-5). Posteriorly, the iliofemoral and ischiofemoral ligaments attach the pelvis to the femur (Fig. 15-6).

Figure 15-5 Anteriorly, the hip joint is covered by an inverted Y–shaped iliofemoral ligament and the pubofemoral ligament.

Figure 15-6 Posteriorly, the iliofemoral and ischiofemoral ligaments attach the pelvis to the femur.

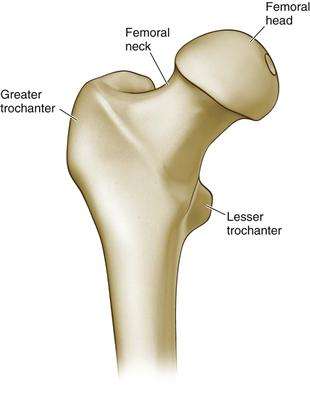

The femoral head tapers down to the femoral neck, which bridges the hip joint to the shaft of the femur (Fig. 15-7). The neck shaft angle averages 127 degrees with an anteversion averaging 14 degrees. The greater and lesser trochanters are prominences about the proximal femur that serve as attachment sites for various tendons and are connected by the intertrochanteric line. The femoral diaphysis has a gentle anterior bow as it extends distally toward the knee. Posteriorly, the diaphysis has a ridge called the linea aspera, which provides an attachment site for muscles and the intermuscular septa.

Figure 15-7 The femoral head tapers down to the femoral neck, which bridges the hip joint to the shaft of the femur. The greater and lesser trochanters are prominences about the proximal femur that serve as attachment sites for various tendons.

Musculature

The muscles of the hip serve to abduct, adduct, flex, extend, externally rotate, and internally rotate the femur relative to the pelvis.

Gluteal Musculature

Posteriorly the gluteus maximus is the largest muscle in the body; it originates from the posterior gluteal line, the iliac crest, the posterior surface of the sacrum and coccyx, and the sacrotuberous ligament (Figs. 15-8 and 15-9). Most of the muscle fibers insert into the iliotibial tract, and a small portion of fibers insert into the gluteal tuberosity of the femur. The gluteus maximus is innervated by the inferior gluteal nerve and functions to extend and externally rotate the hip.

Figure 15-8 Posteriorly, the gluteus maximus originates from the posterior gluteal line, the iliac crest, the posterior surface of the sacrum and coccyx, and the sacrotuberous ligament.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree