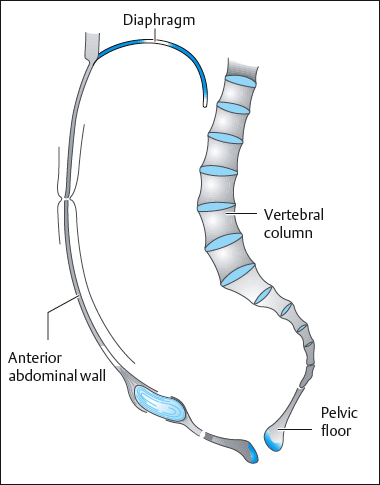

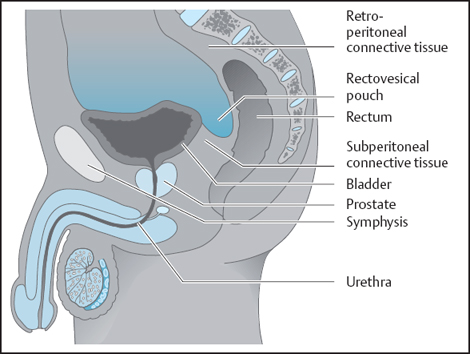

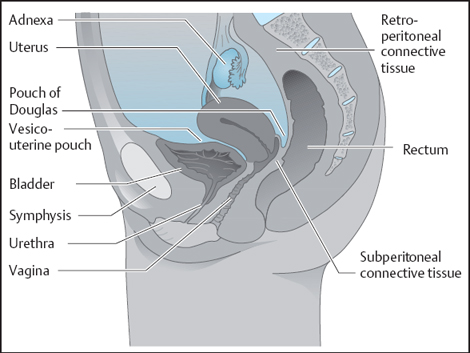

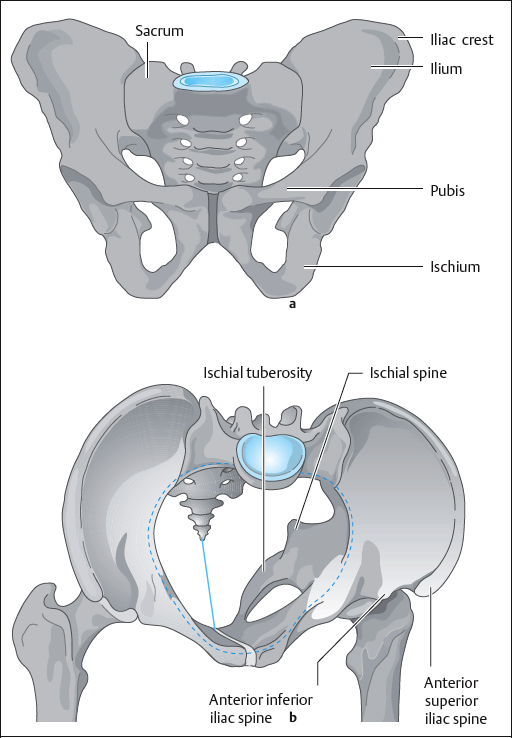

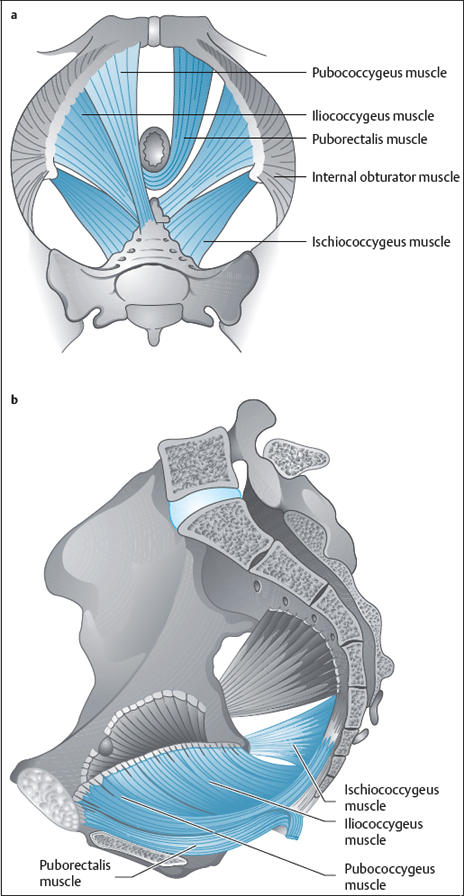

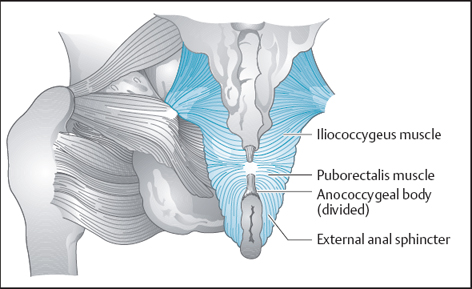

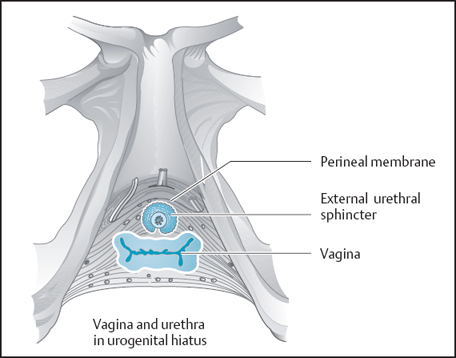

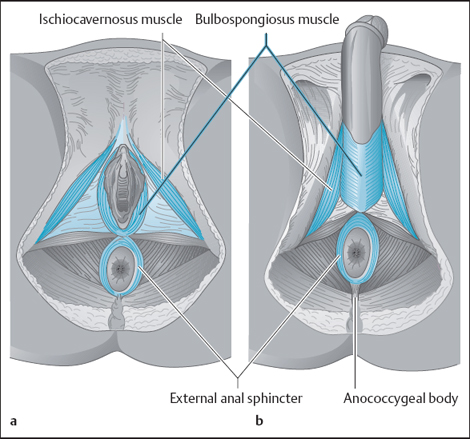

1 Basics The abdominal and pelvic cavities are bounded above by the diaphragm, anteriorly by the anterior abdominal muscles and the bony pelvis, posteriorly by the spinal column and the posterior abdominal muscles, and below by the pelvic floor (Fig. 1.1). The striated muscles known collectively as the pelvic diaphragm close the bony outlet of the pelvic cavity incompletely. There is a common undivided opening in the pelvic floor through which the pelvic organs pass, or where they open. The anterior (ventral) part of this opening is the urogenital hiatus, and the posterior (dorsal) part is the anal hiatus. Each of these openings is sealed off or completed by muscles or fibrous tissue below or outside the pelvic diaphragm. The organs housed in the pelvic cavity, the pelvic organs, are part of different functional systems. The terminal parts of the urinary system—namely the urinary bladder and urethra—lie anteriorly, while the terminal parts of the digestive system—the rectum and anal canal—are found posteriorly. These organs are connected to the abdominal parts of the respective functional systems above and they end in the pelvic floor. Parts of the male genital system lie below or behind the urinary bladder (Fig. 1.2) and lead into the external genitalia outside the pelvic cavity. The organs of the female genital system, lying in the frontal plane between the urinary bladder and the rectum (Fig. 1.3), are similarly linked to the external sex organs below the pelvic floor. The space between the pelvic organs and the bony wall of the pelvis is filled with connective and adipose tissue. Since this space lies below or outside the peritoneum covering the peritoneal cavity, it is sometimes comprehensively called the pelvic extraperitoneal space. However, part of this connective and adipose tissue lies directly under the peritoneum, where it covers the pelvic wall and organs. This tissue is therefore called the subperitoneal tissue. This fibroadipose tissue is continuous with the retroperitoneal connective tissue lying in the retroperitoneal space of the abdominal cavity. In general, the term “subperitoneal connective tissue” now prevails and includes the whole of the pelvic connective tissue. The vessels, nerves, and lymphatics of the pelvic organs run through the pelvic connective tissue. As this short introduction indicates, the pelvic floor is morphologically extremely complex and functionally a very complicated region. What further complicates this region is its complex innervation by the central nervous system. There are both striated and smooth motor connections. The autonomic nervous system innervating smooth motor muscles has both sympathetic and parasympathetic neuronal wiring. The pelvic floor has all forms of sensory input, some informing the brain about skin conditions and muscle stretch relevant to the exteroceptors and muscle proprioceptors. Other forms of sensory input transmit information regarding sensory organ function. Some give the central nervous system (CNS) the specific location of sensory input or pain, while other inputs cause referred sensation or pain. The pelvic floor therefore cannot be viewed in isolation and has to be considered in connection with the surrounding structures, as well as its individual parts. In what follows, therefore, the individual parts of the pelvic cavity and pelvic floor are assembled like building blocks. From this, we will develop an understanding of the interplay between the various organic systems and the pelvic floor. The bony pelvis is formed by the two pelvic bones and the sacrum (Fig. 1.4a). Each pelvic bone (innominate bone, hip bone) consists of three bones that meet at the acetabulum. These are: theilium, ischium, and pubis. Important bony points in the pelvis include the iliac crest, the anterior superior iliac spine, the anterior inferior iliac spine, the pubic tubercle next to the symphysis, the ischial tuberosity, and the ischial spine, as well as the posterior inferior iliac spine and the posterior superior iliac spine. The linea terminalis marks the oblique plane of the pelvic inlet that separates the abdominal and pelvic cavities. The inferior pubic rami, the ischial rami and tuberosities, and the tip of the coccyx form the boundary of the bony pelvic outlet. The pelvic outlet is closed incompletely by the muscles of the pelvic floor, the origin and course of which lie predominantly above the plane of the pelvic outlet (Fig. 1.4b). Posteriorly and inferiorly, two bands—the sacrospinous and sacrotuberal ligaments—stabilize the bony pelvis. These bands complete the foramina formed by the greater and lesser sciatic notches and in part give rise to the muscles of the pelvic floor and the gluteus maximus. Several successive muscular layers close off the bony frame of the pelvic outlet. Its essential component is the pelvic diaphragm, which is composed of the following muscles: the ischiococcygeus (coccygeus) and the levator ani (Fig. 1.5). This muscle arises from the ischial spine and the supraspinous ligament. It is inserted into the lateral aspect of the coccygeal vertebrae. This muscle develops irregularly—i. e., it may be present or only in rudimentary form. Posteriorly, it blends into the levator ani. It is the most dorsal of the muscles of the pelvic floor. The ischiococcygeus is supplied by separate branches arising from the sacral plexus (S3–S4). The levator ani is a composite muscle. It is composed of several bilaterally symmetrical parts. Although there is some dispute in the literature concerning the organization and nomenclature of these parts, the classic division into three parts (pubococcygeus, iliococcygeus, puborectalis) has prevailed and proved reliable when applied to function. The pubococcygeus arises from the internal surface of the superior pubic ramus and is inserted into the lower sacral and the coccygeal vertebrae. The iliococcygeus adjoins the pubococcygeus posteriorly. It does not have a direct bony origin, but arises from a reinforced fascial band that extends in an arc as the tendinous arch of the levator ani, over the pelvic aspect of the fascia of the obturator internus, to the ischial spine. It is inserted into the lower sacral and the coccygeal vertebrae, where it interdigitates with the pubococcygeus. In life, the parts of the levator—namely, the pubococcygeus and iliococcygeus, together with the ischiococcygeus—are layered in a flat muscular plate that seals the pelvic outlet posteriorly and laterally. The puborectalis has its bony origin below the pubococcygeus on the inner surface of the pubic bone. It is not inserted into bone. Rather, the puborectalis muscles of both sides interdigitate behind the rectum and in this manner form a muscular sling posterior to the rectal wall at the level of the anorectal flexure. The muscular sling is continuous posteriorly, while anteriorly it opens to form the anal and urogenital hiatuses. The puborectalis is supplied by separate branches from the sacral plexus and the pudendal nerve [Roberts et al. 1988]. The levator ani, like all other skeletal muscles, is surrounded by fascia. It is termed the superior fascia of the pelvic diaphragm on the side facing the pelvic cavity, and the inferior fascia of the pelvic diaphragm on the side facing outward. The bony pelvis presents characteristic sex-specific differences; for instance, in the female the pelvic cavity is wider and the ischial tuberosities further apart than in the male. Consequently, the muscles of the pelvic floor also differ. The muscles surrounding the levator arch are further apart in the female pelvis than in the male. In the latter, the muscles are more strongly developed and, because of the narrower bony pelvis, take on more of a funnel shape than in the female (Fig. 1.6). In the female pelvis, the muscles of the pelvic floor are often infiltrated by fibrous tissue, and this can frequently be seen even during prenatal stages of development [Fritsch and Frohlich 1994]. It is generally thought that the opening between the limbs of the levator is closed off externally and below by a muscular layer, termed the urogenital diaphragm. This has been debated, especially in the morphological literature [Oelrich 1983]. In the male pelvis, the anterior opening between the limbs of the levator ani, the urogenital hiatus, is closed off by a thin sheet of muscle and connective tissue. This muscle, known as the deep transverse perineal muscle, is the inferior part of the external urethral sphincter. Its fibers first surround the urethra in semicircular loops, then run horizontally through the perineum and so spread out as the deep transverse perineal muscle. These striated muscles are innervated by the pudendal nerve, which is believed to carry visceromotor as well as somatic fibers [El-badawi and Schenk 1974]. In the female pelvis, the existence of the deep transverse perineal muscle is controversial. What has been determined is that the urogenital hiatus is filled with connective tissue (Fig. 1.7), termed the perineal membrane. Between the urogenital and anal hiatuses lies a firm connective-tissue mass, in which several muscles from outside the pelvic floor meet. This is the perineal body. The striated external anal sphincter is intimately connected with the puborectalis, a part of the pelvic musculature. Toward the anus, it continues into the puborectalis sling, where it begins by forming a semicircle around the anal canal. Anteriorly, the open ends combine with the puborectalis to form a muscular sling, by which they are fastened indirectly to the anterior part ofthe pelvic ring. Beyond this point, the external anal sphincter takes several turns around the anal canal. Posteriorly, this elevated portion of the external anal sphincter is attached to the coccyx by the anococcygeal body (formerly called the anococcygeal ligament) [Federative Committee on Anatomical Terminology 1998]. In the perineum, the external anal sphincter also takes a semicircular course—i. e., it is open posteriorly, closed anteriorly, and anchored in the connective tissue of the perineal body [Fritsch et al. 2002]. The perineal segment of the external anal sphincter forms a muscular sling with both the smooth muscle of the internal anal sphincter and the longitudinal smooth muscle (stratum longitudinale) of the anal canal. The essential sex-specific differences in the external anal sphincter include a thick and elevated supraperineal part in the male, in contrast to the female, where the perineal part is the most strongly developed. The pudendal nerve supplies the external anal sphincter. The perineal body also gives rise to the bulbospongiosus muscle. In the male, this muscle envelops the expanded end of the corpus spongiosum. It is continuous with the penile fascia on the dorsum of the penis. In the female, the muscle envelops the vestibular bulb, an erectile body that surrounds the vestibule of the vagina bilaterally (Fig. 1.8). An ischiocavernosus muscle arises on the external surface of the pubic rami on each side, surrounding the crus penis in the male and the crus of the clitoris in the female. The bulbospongiosus and ischiocavernosus muscles lie in the connective tissue of the superficial perineum and are supplied by the pudendal nerve. The organs situated in the pelvic cavity are collectively called the pelvic organs. The organs grouped together here belong to totally separate functional systems. They will be described specifically for each sex. The urinary bladder (vesica urinaria) lies anteriorly in the pelvic cavity, which is directly behind the pubic symphysis (Fig. 1.9). It is a hollow muscular organ that mainly consists of thebody of the bladder and continues into its apex anteriorly. The fundus faces posteriorly and down-ward and, like the bladder neck, is in contact with the crura of the levator ani. The bladder neck is continuous with the urethra, which in the male leaves the pelvic cavity by traversing the prostate and the deep transverse perineal muscle, to continue as the spongy urethra in the corpus spongiosum of the penis. On the posterior aspect of the bladder lie the paired seminal vesicles. They are accompanied medially by the ampulla of the deferent duct (vas deferens). Between these two organs, a ureter enters the bladder on each side. Below the bladder, the prostate gland lies in direct contact with the anterior portions of the muscles of the pelvic floor. In the posterior part of the narrow male pelvic cavity lies the rectum. This bowel segment, about 15cm long, follows the curvature of the caudal spinal column—i. e., the sacrum and the coccyx. At the anorectal flexure, where the puborectalis muscle forms a sling around the intestine, the rectum continues into the anal canal, which in turn is surrounded by the external anal sphincter (see above). The external male genitalia include the penis, the scrotum, and the scrotal coverings. The penis consists of the paired corpora cavernosa and the unpaired corpus spongiosum surrounding the male urethra. It ends in the glans penis. The scrotum contains the two testes, which, being the male gonads, are internal genital organs, but for functional reasons are located outside the pelvic cavity. The vascular and nervous supply reaches the scrotum by way of the spermatic cord, and the deferent duct transports the spermatozoa toward the spongy urethra. From the scrotum, the spermatic cord reaches the abdominal and pelvic cavities through the inguinal canal. In the female pelvic cavity, the urinary bladder is also the most anterior organ. It continues into the short female urethra. In the frontal plane between the urinary bladder and the rectum are inserted the structures of the female genital system (Fig. 1.10). These include the ovary, uterine tube, uterus, and vagina. The ovary and uterine tube lie laterally in the pelvic cavity. Collectively, these are called the adnexa. The uterine tube on both sides leads into the uterus, which is divided into the fundus, corpus, and cervix. Normally, the uterus projects freely into the pelvic cavity, with the corpus angled forward (anteflexed) on the cervix, and the whole uterus inclined forward (anteverted) from the vagina. The cervix projects freely into the vagina, which in turn runs a course close to the crura of the levator ani muscle. The frontal orientation of the internal female genitalia creates two hollows in the peritoneal cavity—the vesicouterine pouch (excavatio vesico-uterina) and the rectouterine pouch (excavatio rectouterina). The latter is also known as the pouch of Douglas. This is the lowest point in the female abdominal cavity. Laterally, the rectouterine folds—peritoneal folds that carry the autonomic nerves for the pelvic organs—form the boundary of this peritoneal pouch. These include the labia majora, the labia minora, and the vestibule (Fig. 1.11), with the vestibular glands and the clitoris. Clinically, the term vulva includes the external genitalia, the urethral orifice and the vagina, as well as the fat pad overlying the symphysis, the mons pubis. The pelvic connective tissue consists mostly of loose areolar and adipose tissue. It enables the pelvic organs to slide and shift. Because of its relation to the peritoneum, it is called the subperitoneal fascia space (spatium subperitoneale). It blends seamlessly with the areolar and adipose tissue of the retroperitoneal space. The subperitoneal space usually contains some demonstrable thickening of connective fibers, but nowhere do these have the characteristics of the type of ligament found in the motor system. Beyond this, there is fibrous connective tissue that is part of the parietal fascia of the pelvis (formerly endopelvic fascia), which uniformly covers the walls of the pelvis. In contrast, there is no uniform visceral fascial covering for the pelvic organs. Rather, those pelvic organs that are enclosed by a muscular layer (hollow organs and uterus) are surrounded by loose areolar adventitia containing nerves and vessels (Fig. 1.12). Parenchymatous organs such as the prostate and seminal vesicles are separated from surrounding structures by a capsule. Comparative investigations into the development of the pelvic fascia before birth and in the adult have demonstrated that the pelvic fascia shows the same subdivisions in the male and in the female [Fritsch 1994], being essentially tied to the development of vessels and nerves. Functionally, a knowledge of the connective-tissue structures and their subdivisions is especially important in the female pelvis, where the following connective-tissue spaces and structures can be distinguished from back to front between pelvic organs and the pelvic walls. In front of the sacrum and coccyx lies a small presacral space containing primarily veins and loose areolar tissue. It is separated from the rest of the sub-peritoneal fascia by the parietal pelvic fascia, which here is also known as the presacral fascia.

1.1 Anatomy and Physiology of the Pelvic Floor

Overview

Overview

The Bony Pelvis

The Bony Pelvis

Muscles of the Pelvic Floor

Muscles of the Pelvic Floor

Ischiococcygeus (Coccygeus)

Ischiococcygeus (Coccygeus)

Levator Ani

Levator Ani

Urogenital Diaphragm

Urogenital Diaphragm

Muscles Below and External to the Pelvic Floor

Muscles Below and External to the Pelvic Floor

Pelvic Organs

Pelvic Organs

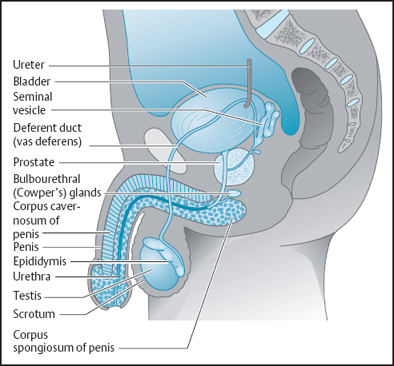

Male Pelvic Organs

Male Pelvic Organs

External Male Genitalia

External Male Genitalia

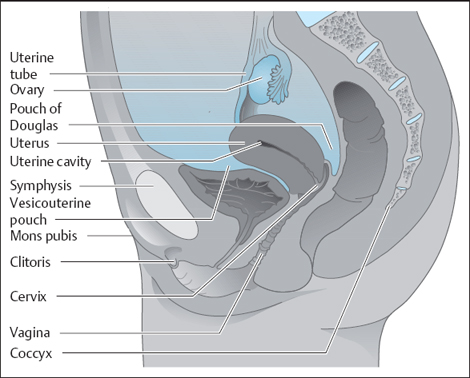

Female Genitalia

Female Genitalia

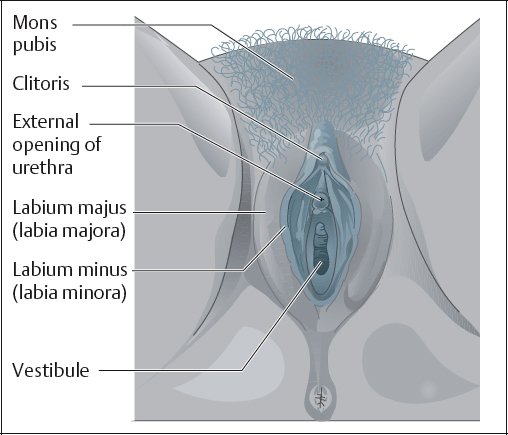

External Female Genitalia

External Female Genitalia

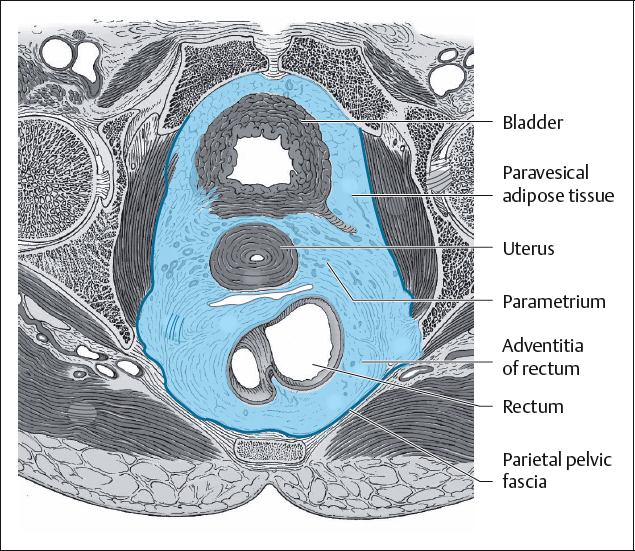

Pelvic Connective Tissue

Pelvic Connective Tissue

The Subperitoneal Space

The Subperitoneal Space

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree