6 Treatment for Rectal and Anal Disorders

6.1 Anal Dysfunction after Delivery

Introduction

Introduction

One of the most socially devastating sequelae of vaginal delivery is anorectal incompetence. The expulsive forces as the fetal head descends through the birth canal lead to overstretching of both nerve and muscle tissues. These tissues do not always undergo full recovery. Such trauma can result in symptoms of anal sphincter incompetence, including incontinence of feces or flatus and fecal urgency [Sultan et al. 1993a]. Symptoms such as these are both embarrassing and debilitating, and while such symptoms may be transient following a first vaginal delivery, subsequent deliveries are likely to cause further deterioration [Fynes et al. 1999].

The Prevalence of Anorectal Symptoms

The Prevalence of Anorectal Symptoms

Prevalence in General Populations

Prevalence in General Populations

In a systematic review of the literature on fecal incontinence, Chiarelli et al. [2002] derived age-specific and gender-specific rates of fecal incontinence from the literature. To be included, studies had to fulfill the following a priori criteria: they had to have a community-based sampling frame, a response rate greater than 65%, a sample size of more than 125 participants per gender group, and use self-reporting of symptoms, as well as a validated instrument for measuring incontinence. Age-stratified prevalences were pooled across each of the age and gender strata to derive the age-stratified prevalence of fecal incontinence in women (Table 6.1). Papers in this study were limited to high-quality, reasonably large, community-based studies with high response rates, in order to avoid potential biases. Nevertheless, the study had some limitations, in that results from abstracts or searches for unpublished studies (the so-called “gray literature”) were not included and there was no method available to assess publication bias. However, since the included studies focused on prevalence estimates and not effect sizes, there was no reason to believe that they would be subject to the same publication bias—i. e., that studies with positive results are more likely to be published than those with negative results. Despite these limitations, this was the first meta-analysis of the prevalence of fecal incontinence to be undertaken.

The prevalence of incontinence increases with age; it is roughly seven to eight times higher in the over-80 age group in comparison with the under-30 age group. Although the study was able to generate age-stratified prevalences and to allow for estimation of the magnitude of fecal incontinence within populations, the following factors need to be considered:

- The results were pooled despite some heterogeneity. Pooling was done using a random effects model. The random effects model assumes that the studies done are a random sample of all possible studies.

- The pooled studies reflect differing definitions and severities of incontinence. It is therefore not possible to say whether the pooled estimate reflects the prevalence of mild, moderate, or severe incontinence, nor whether it reflects current incontinence, or incontinence at any time.

- The studies provide insufficient description of potential confounders [Chiarelli et al. 2002].

| Age group | Women with fecal incontinence |

|---|---|

| I 30 | 0.019 |

| 30–39 | 0.046 |

| 40–49 | 0.078 |

| 50–59 | 0.108 |

| 60–69 | 0.137 |

| 70–79 | 0.107 |

| 80 + | 0.156 |

The Prevalence of Anal Dysfunction in Postpartum Women

The Prevalence of Anal Dysfunction in Postpartum Women

Estimates of the prevalence of fecal incontinence vary depending on the sample studied and the definitions applied. In a large international study including 7879 women, the reported prevalence of fecal incontinence at 3 months postpartum was 9.6% [MacArthur et al. 1997]. Lower rates of 2% [Zetterstrom et al. 1999] and 5 % [Sultan et al. 1993a] have been reported for primiparous women, whereas higher rates of 19% have been reported for multiparous women [Sultan et al. 1993a]. Not surprisingly, a substantially higher rate of 41% was found for women who sustained a third-degree tear during childbirth [Sultan et al. 1993a]. However, comparison of these rates is limited due to differences in definitions: for example, some studies define anal incontinence as including symptoms of flatus incontinence [Sultan et al. 1993a, MacArthur et al. 1997], whereas others do not [MacArthur et al. 1997]. Some report fecal incontinence and flatus incontinence separately [Zetterstrom et al. 1999]. Moreover, some studies do not clearly report the definitions that were used [Fynes et al. 1999].

The study by Chiarelli et al. [2002] reports on the prevalence of, and factors associated with, fecal incontinence and its precursors among women at 12 months postpartum. In order to address the shortcomings of the definitions used in previous studies, prevalence rates were calculated separately for each of the indicators of fecal incontinence and its precursors—namely, solid stool incontinence, liquid stool incontinence, flatus incontinence, soiling, and fecal urgency. In the light of previously demonstrated associations between parity and fecal incontinence, the prevalence rates were calculated separately for primiparous and multiparous women. The study is confined to women at higher risk of anal sphincter damage—namely, those who had an instrumental delivery and/or delivered a high-birthweight baby 4000 g) [Chiarelli 2001]. Women took part in a baseline hospital-based interview and a 12-month follow-up telephone interview. The main outcome measures were frank fecal incontinence (solid and/or liquid stool) and precursor symptoms (flatus incontinence, soiling, and/or fecal urgency) at 12 months postpartum.

The study showed that the prevalence of fecal incontinence was 6.9% (2.6% solid stool, 4.9 % liquid stool). The prevalence of precursor symptoms was 32.4% (24.4% flatus incontinence, 10.9 % soiling, 14.8 % fecal urgency). Concurrent urinary incontinence and postpartum constipation were significantly associated with both frank fecal incontinence and precursor symptoms. In addition, joint hypermobility and older maternal age were associated with frank fecal incontinence, while inability to stop the urine flow and multiparity were associated with precursor symptoms [Chiarelli 2001].

Relationship between Anal and Urinary Incontinence

Relationship between Anal and Urinary Incontinence

Since vaginal delivery is seen to contribute strongly to the genesis of fecal incontinence, it is not unexpected that the symptoms of fecal incontinence should be linked to those of urinary incontinence. A number of studies have explored this phenomenon.

Roberts et al. [1999] studied concurrent urinary and fecal incontinence using a cross-sectional community study. They found that more than half of women with fecal incontinence also experienced urinary incontinence. They also calculated the odds ratio for a woman being fecally incontinent in the presence of urinary incontinence as 3.0 (95 % confidence interval, 1.9 to 4.8), while Kok et al. [1992] estimated the odds ratio of being fecally incontinent in women with urinary incontinence relative to those without urinary incontinence as 5.8 (95% CI, 1.59 to 21.02) in women aged 60–84.

Other studies have examined the relationship between urinary incontinence and fecal incontinence. Khullar et al. [1998] reviewed 465 women presenting for urodynamic assessment. Of the 86 women (18.5%) who were diagnosed with detrusor instability, 26 (30 %) also had fecal incontinence. Of the 183 women (39.4%) diagnosed as having genuine stress urinary incontinence, 30 (16.4%) also had fecal incontinence. This association between detrusor instability and fecal incontinence was supported by the study by Meschia et al. [2002]. Concurrent urinary and fecal incontinence have also been shown to be significantly associated with the presence of pelvic organ prolapse [Jackson et al. 1997].

Pelvic Floor Trauma and Childbirth

Pelvic Floor Trauma and Childbirth

There are a number of anatomical and physiological factors that contribute to anal sphincter competence, including muscular, neurological, and connective-tissue factors. Each of these may be associated with trauma during vaginal delivery.

Muscle Damage

Muscle Damage

In order to examine the implications of muscle stretch during vaginal delivery, Lien et al. [2004] undertook a study of simulated birth. They concluded that the medial fibers of the pubococcygeus muscles undergo the largest stretching during delivery of the fetal head (stretch ratio of 3.26 their original length), while parts of iliococcygeus, pubococcygeus, and puborectalis muscles reached maximal stretch ratios of 2.73, 2.5, and 2.28, respectively.

DeLancey [1993b] summarized the inciting nature of childbirth injuries succinctly in stating, “Care is needed to put the findings of studies of childbirth injury in proper context. On the one hand, what may at first seem to be a minor injury can become clinically important years later, after age and disease have taken their toll.” DeLancey suggests that there are three phases of pelvic floor tissue damage and repair. Firstly, the initial muscle and nerve damage that occurs with vaginal delivery, followed by the repair phase, in which the damaged tissues repair themselves; finally, there is a maintenance phase in which factors such as age and other diseases have an impact on the healed tissues over long periods of time [DeLancey 1993b]. This hypothesis is supported by earlier work by Swash et al. [1985], who found that denervation of the pelvic floor sphincters led to urinary incontinence and fecal incontinence. In electromyographic studies, they also found that nerve damage initiated at childbirth appears to progress over a number of years in the face of repeated straining at stool and perineal descent.

Evidence supporting this concept of tissue damage during vaginal delivery is provided by in vivo physiological studies showing that vaginal delivery is associated with nerve damage [Snooks et al. 1984, 1990, Sultan et al. 1993a, Mallet et al. 1994], pelvic floor muscle damage [Dimpfl et la. 1998, Chaliha et al. 2001], and damage to the supporting structures within the genitourinary tract [Allen et al. 1990, DeLancey 2002].

Both childbirth and aging lead to histomorphological changes within the pelvic floor muscles, consistent with changes of a myogenic origin. In a cross-sectional study of 62 female cadavers of childbearing age, vaginal delivery was reported to be the most important factor leading to histomorphological changes consistent with changes of myopathic origin such as fibrosis, centrally located nuclei, and variation in fiber diameter [Dimpfl et al. 1998]. Muscular damage and episiotomy during labor may lead to scarring, particularly of the puborectalis muscle. This scarring can be related to unilateral muscle dysfunction or even complete absence of contractility [Deindl et al. 1995, Schüssler et al. 1994].

Anal pressure studies have shown that vaginal delivery is associated with adverse effects on anal sphincter function, including maximal anal squeeze pressure as well as resting pressure [Chaliha et al. 2001]. Injury to the anal sphincter mechanism can be a result of direct trauma and disruption of the anal sphincter [Sultan et al. 1993a]. The first vaginal delivery is the most important risk factor for mechanical injury to the anal sphincter [Donnelly et al. 1998, Sultan et al. 1993b].

Nerve Damage

Nerve Damage

The pudendal nerves tend to be fixed at the ischial spines, so that their distal segments are predisposed to traction injuries during labor. While some postpartum urinary incontinence may recover following childbirth, nerve damage does not necessarily do so. Snooks et al. [1984] found that 60 % of the women studied had sustained pudendal nerve damage, as measured 48-72 h postpartum. However, in the majority of women, this nerve damage had resolved by 6 months postpartum. Sultan et al. [1993a] found similar results 6 months postpartum. Snooks et al. [1990] followed up 58% of the women in the original study and concluded that pudendal nerve damage with partial recovery may persist and become more marked 5 years after vaginal delivery.

Mallet et al. [1994] examined nulliparous women neurophysiologically at 8 weeks postpartum and followed up 6 years later. They concluded that further changes in pelvic floor neurophysiology occur with time. These changes do not appear to be related to further childbearing. Incontinent women in this study had significantly greater nerve and muscle function dysfunction than continent women. Absolute parity and further childbearing in this group of women had no effect, and it was concluded that the majority of neuromuscular damage occurs with the first vaginal delivery. Again, the unifying concept of pelvic floor disorders, as postulated by Swash et al. [1985] supports these findings.

Chaliha et al. [2001] prospectively studied changes in anal sensation in pregnant women and followed these women 6 months postnatally. No significant changes were seen in measurements of minimal anal sensation. Cornes et al. measured anal sensation at 10 days postpartum and found that it was significantly reduced. When measurements were conducted again 6 months postpartum, no reduction of anal sensation was found. These findings suggest that anal sensation may be impaired by vaginal delivery, but that this recovers with time.

In contrast to anal sphincter injuries, in which the first vaginal delivery is the most important risk factor, pudendal nerve injury is more common with successive vaginal deliveries and the damage is more likely to be cumulative, with symptoms becoming manifest many years later [Snooks et al. 1990, Fynes et al. 1999].

Supporting Tissue Damage

Supporting Tissue Damage

The connective tissues within the pelvic floor play a major role in supporting the pelvic organs [DeLancey 1993a]. The great majority of symptomatic prolapse occurs in multiparae, with only 2 % occurring in primiparous women [Cardozo 1988, 1995, Mant et al. 1997]. Patterns of denervation injury across the pelvic floor appear to be correlated with deficits of support and function [Smith et al. 1989, Smith 1994].

Obstetric Risk Factors for Anorectal Dysfunction

Obstetric Risk Factors for Anorectal Dysfunction

Pregnancy

Pregnancy

In a review of studies on vaginal delivery and anal function, Rieger and Wattchow [1999] highlighted the lack of anal sphincter disruption in women following elective cesarean deliveries in comparison with women after vaginal deliveries. They also highlighted the fact that emergency cesarean section is associated with changes in anal continence, providing further support for the view that it is vaginal delivery rather than pregnancy that affects sphincter function.

Normal Vaginal Delivery

Normal Vaginal Delivery

Maternal morbidity following vaginal delivery is commonly associated with the pelvic floor. However, pelvic floor trauma is not only associated with deliveries in which obvious trauma has been inflicted on the pelvic floor—e. g., tears, episiotomies, and assisted deliveries. In many cases, pelvic floor trauma is occult and is not capable of being detected by visual inspection of the perineum.

Advances in assessment techniques for evaluating the anal sphincter mechanism using ultrasonography have allowed for wider exploration of anal sphincter trauma following vaginal deliveries. Ultrasonography is accurate, easy to use, and comfortable for the patient, and has allowed much broader exploration of anal sphincter damage during childbirth.

The use of ultrasonography and nerve testing procedures has revealed that about one-third of women undergo some degree of trauma to their anal muscles and nerves during vaginal delivery, but that such trauma is not necessarily visible in the immediate postpartum period [Sultan et al. 1993]. However, most women who present in later life with symptoms of fecal incontinence are found to have sphincter defects on ultrasonography. Thus, it is clear that vaginal delivery without perineal damage can be associated with anal sphincter disruption [Deen et al. 1993].

In a prospective study of 59 previously nulliparous women through two successive vaginal deliveries, Fynes et al. [1999] clearly showed that women with transient symptoms of fecal incontinence or occult anal sphincter damage with their first delivery have a high risk of fecal incontinence after a second vaginal delivery. In a study of 242 women following vaginal delivery, Ryhammer et al. [1995] clearly showed an increased strength association between permanent flatus incontinence, repeated childbirth, and an odds ratio of 8.3 for permanent flatus incontinence following the third vaginal delivery. This study only included women who showed no obvious signs of anal sphincter damage immediately following childbirth.

In the study of simulated birth by Lien et al. [2004], it was deduced that the size of the fetal head would have a direct impact on the stretching of the pelvic floor muscles, with tissue stretch ratios being shown to be proportional to fetal head size.

Classification of Pelvic Floor Trauma

Classification of Pelvic Floor Trauma

The standard practice definitions of pelvic trauma are as follows:

- First-degree tear: a perineal laceration extending through the vaginal mucosa and perineal skin only.

- Second-degree tear: a laceration extending into the perineal muscles.

- Third-degree tear: a laceration involving the external anal sphincter.

- Fourth-degree: a laceration affecting both the anal sphincter and the anorectal mucosa.

Third-Degree Tears

Third-Degree Tears

The foremost risk for incontinence is considered to be a third-degree tear. Tears such as these occur in 0.5–2.4 % of vaginal deliveries. Vaginal delivery with third-degree tears is associated with a stronger probability of disturbed anal continence than vaginal delivery without tear. The review by Rieger and Wattchow [1999] clearly shows an increase in a number of measures of anal continence in women after delivery with third-degree tears in comparison with women without tears.

In a retrospective analysis of 34 women who sustained a third-degree or fourth-degree tear during a vaginal delivery and 77 women who had not, Sultan et al. [1994] explored the risk factors for third-degree tears. After careful analysis, the factors shown in Table 6.2 were found to be significantly associated with third-degree tears. Factors shown not to be associated with third-degree tears were induced labor, shoulder dystocia, and epidural. Forty-two percent of women in this study who developed a third-degree tear without an instrumental delivery did so despite having a mediolateral episiotomy. The benefits of episiotomy have not been well studied in relation to third-degree tears [Sultan et al. 1994].

| Factor | Relative risk (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Forceps delivery | 13.3 (7.7 to 23) |

| Primiparity | 7.0 (3.3 to 14.8) |

| Baby’s weight | 2.9 (1.5 to 5.8) |

| Persistent occipitoposterior position | 4.4 (1.6 to 12.2) |

Episiotomy

Episiotomy

Episiotomy is a widely performed surgical procedure, with doubtful benefit to the patient. Overt injury to the anal sphincter can be the result of spontaneous laceration or may result from the extension of an episiotomy. Signorello et al. [2000] retrospectively studied three groups of women following vaginal delivery. The groups consisted of an episiotomy group, a tear group (with no episiotomy, but sustaining a second-degree or third-degree tear), and an intact group. Statistical comparisons between the groups revealed that 10% of the episiotomy group experienced fecal incontinence 3 months after delivery, while women in the tear group and intact group had less than half that risk. In addition, the study showed that one-quarter of the women in the episiotomy group experienced flatus incontinence 6 months postpartum, in comparison with 10–13% of the women in the other groups [Signorello et al. 2000].

Midline episiotomy in particular is associated with higher rates of third-degree and fourth-degree tears than mediolateral episiotomies. A clear association has been shown between significant anal sphincter trauma and midline episiotomy [Fitzpatrick and O’Herlihy 2000]. Midline episiotomy is a risk factor for postnatal anal sphincter incompetence independently of the woman’s age, the birthweight of the baby, the length of the second stage, and complications of labor and forceps delivery [Signorello et al. 2000].

The potential influence of epidural anesthesia on the incidence of episiotomies needs to be taken into consideration.

Instrumental Vaginal Delivery

Instrumental Vaginal Delivery

Forceps delivery has been shown to be associated with significantly increased risk to anal continence mechanisms [Sultan et al. 1993a, 1993b, 1998, Donnelly et al. 1998, Fynes et al. 1999]. It has been shown that instrumental delivery is associated with an eightfold increase in the risk of anal sphincter trauma [Donnelly et al. 1998]. More than 50% of third-degree tears occur with instrumental delivery, although it is recognized in less than 5 % of such deliveries [Sultan et al. 1994] and forceps appear to be more significantly associated with third-degree tears than vacuum extraction (ventouse delivery). While the risk of trauma is seen to be less with ventouse extraction than with forceps delivery, there is still an elevated risk of damage with any operative vaginal delivery [Fitzpatrick and O’Herlihy 2000].

In the study by Fitzpatrick and O’Herlihy [2000] in nulliparous women, significant perineal injury was shown to be associated with instrumental delivery undertaken due to failure to advance in the second stage of labor, while in women who had had a previous vaginal delivery, the most significant risk factor was the baby’s weight.

Symptoms of Anorectal Dysfunction

Symptoms of Anorectal Dysfunction

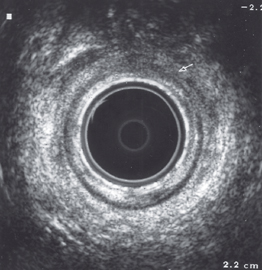

Endoanal ultrasonography has allowed very accurate assessment of anal continence mechanisms. The morphology of the tissues lends itself well to ultrasound imaging. The internal and external anal sphincters, puborectalis muscles, and rectovaginal septum can be seen well. Endoanal ultrasound is usually carried out with a high-frequency (10 MHz) endoanal probe [Kamm 1994].

Several studies have explored the symptoms of dysfunctional bowel control from the point of view of subjective assessment. It is important to realize that not all women with external anal sphincter defects that are identified on anal endosonography or seen at delivery report symptoms of anal dysfunction [Sultan et al. 1993a, Kamm 1994] and that women with a surgically repaired external anal sphincter still report symptoms of lack of control [Beck and Laurberg 1992]. In general terms, passive incontinence (fecal incontinence in which the patient is unaware of the loss) is associated with internal anal sphincter defects, while fecal urgency (with or without incontinence) is associated with defects in the external anal sphincter [Engel et al. 1995].

Impaired Anorectal Sensation

Impaired Anorectal Sensation

The stimulus to the initiation of defecation is distension of the rectum. Feces are held in the descending and sigmoid colon. Distension of the left colon leads to peristaltic waves, which move the fecal mass down into the rectum. Receptors in the rectum are stretch receptors, with additional stretch receptors in the surrounding pelvic floor muscle tissues. In the presence of overstretched pelvic floor muscles, receptors in pelvic floor will provide decreased sensation of the need to defecate. This may contribute to constipation and overdistension of the rectum.

Impaired anorectal sensation can also be associated with an abnormal external anal sphincter response to rectal filling in which recruitment of sphincter activity is reduced. Adequate rectal sensation is necessary for the external anal sphincter to react promptly.

Rectoanal Inhibitory Reflex and Sampling

Rectoanal Inhibitory Reflex and Sampling

The rectoanal inhibitory reflex is the threshold amount of rectal distension needed to elicit relaxation of the smooth-muscle internal anal sphincter (IAS), allowing the sensitive nerve endings to distinguish between solids, liquids, and gases. As the IAS relaxes, the external anal sphincter (EAS) pressure automatically increases.

When the rectoanal inhibitory reflex is absent, there is an inability to distinguish the rectal contents, or there is an absence of sensation altogether, resulting in fecal urgency or passive fecal incontinence.

Internal Anal Sphincter Defects

Internal Anal Sphincter Defects

Both the internal and external anal sphincters need to be able to maintain an airtight seal. Failure to do this means that patients may experience loss of solid or liquid feces concurrently, because of the inability to distinguish between the two. Continence to mucus and feces is maintained by tonic contraction of the internal anal sphincter during resting conditions and gradual rectal filling. Investigations have shown that up to 25 % of patients reporting fecal incontinence had low resting pressures and absent IAS relaxation, with rectal distension and marked descent of the pelvic floor.

External Anal Sphincter Defects ( Fig. 6.1)

Fig. 6.1)

Normally, defecation can be deferred for long periods of time, as the urge to defecate is inhibited by contraction of the EAS. However, if the EAS is not strong enough, it may be insufficient to depress the urge. The EAS must be strong enough to push stool back up into the rectum, which accommodates to hold the fecal bolus.

The urge to defecate is suppressed by complex cortical inhibition of the basic reflexes of the anorectum. The EAS is contracted long enough for IAS to recover its normally high resting tone. If the EAS cannot reach its required resting tone or is only strong enough to hold a contraction for a very short time, fecal urgency results.

The EAS may fail to contract in time to compensate for IAS relaxation caused by rectal distension. This can occur when the rectal volume that induces IAS relaxation is lower than the volume that evokes rectal sensation and increased EAS activity, or when the EAS is present but the response is delayed.

Fecal incontinence results when the EAS is unable to hold until the toilet is reached. In such cases, the patient is aware that incontinence has occurred. One episode of fecal urgency with fecal incontinence can trigger an urgency response to any rectal filling. An important management tool for patients with fecal urgency is to provide them with an understanding of the “urgency cycle” (Fig. 6.2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree