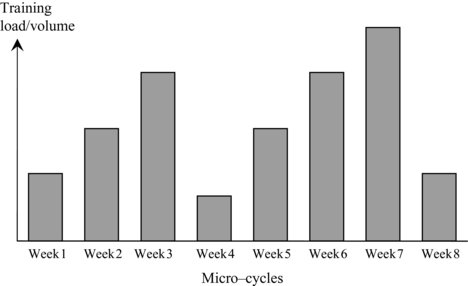

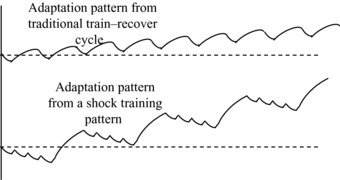

Meso-cycles that use such a 4-week training block place a great deal of short-term accumulative stress on the body. It is possible that full recovery between sessions or even micro-cycles is not achieved until week four. Prior to this the athlete will accumulate fatigue as the overall training load increases. This in turn can have implications for the trainability of particular fitness attributes (Balyi 2001). For example the training of speed, maximal strength, technique and the learning of new skills should be emphasised during the early weeks of each four-week cycle, when the athlete is relatively fresh and receptive to such methods. During later weeks the most trainable attributes will be cardiovascular endurance, anaerobic power, local muscular endurance and speed endurance. The improvements in fitness from such a pattern of training are illustrated in Figure 9.3.

The training year

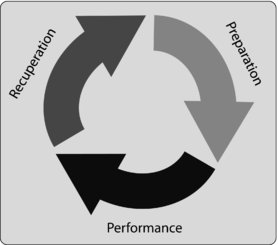

The most common macro-cycle is the training year, which in turn consists of a number of meso-cycles and micro-cycles. Every training year consists of a preparation phase, a performance phase and a recuperation phase (Figure 9.4), which vary in length depending on the competition schedule of each particular sport.

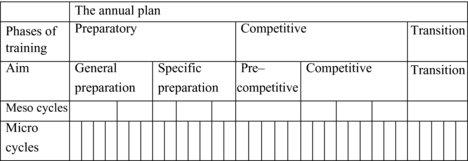

The preparation phase itself may be considered in greater detail and further divided into a general preparation period, a specific preparation period and a pre-competition period (Matveyev 1965). This gives a training year with five distinct phases: general-conditioning period; specific-conditioning period; pre-competition period; competition (or performance) period; transition (or recuperation) period (see Table 9.2). Figure 9.5 shows Bompa’s (1999) representation of the annual training plan.

Table 9.2 Training phases

| Phases of the training year (Matveyev 1965) | Aim |

| General conditioning period | To develop a broad base of fitness involving strength, power, local muscular endurance, cardiovascular fitness and flexibility |

| Specific conditioning period and pre-competition period | To provide a progressive transition from the broad general fitness towards the highly specific fitness required by competition |

| Competition (or performance) period | To maintain their hard earned fitness, remain injury free and peak for key competitions |

| Transition (or recuperation) period | To achieve full recuperation in readiness for the general preparation period ahead |

General conditioning period

The aim of the general conditioning period is to develop a broad base of fitness that acts as a foundation for the high-intensity, sport specific training that follows. This period predominantly focuses on strength endurance (8–20 repetitions, 3–5 sets, 3–4 days per week) (Plisk and Stone 2003), but also includes some power exercises, cardiovascular fitness, flexibility training and technique work. This phase is characterised by a progressive increase in both volume (primary aim) and intensity (secondary aim) of training.

Note: Although this period is about general preparation, athletes should not neglect their practice of sport specific skills. These skills should be incorporated into the training via dedicated, short duration, high quality practices, or included as part of a functional dynamic warm-up. This will help ensure that athletes maintain the skills and coordination required in competition. For example, during this period sprinters may be focusing many of their track sessions on speed endurance, rather than pure speed. This, however, does not preclude the athletes performing short bursts of maximum speed running, or quick feet coordination drills, as part of their warm-up.

Specific conditioning and pre-competition period

The aim of this phase is to provide a progressive transition from the broad general fitness towards the highly specific fitness required by competition. It can last from a few weeks (English Premiership football) through to two or three months (sprinters) and consists of a progressive increase in intensity and decrease in volume of training with a greater emphasis of sports specific activities and skills, functional speeds and actual sports practices. Strength training focuses on basic strength (4–6 repetitions, 3–5 sets, 3–5 days per week) (Plisk and Stone 2003).

Competition period

The length of the competition period varies for different sports (soccer — 9 months, athletics — 3–4 months, cricket — 5 months); however the aims remain the same. Athletes need to maintain their hard earned fitness, optimise performance, remain injury free, and peak for key competitions. This phase usually focuses on lower volume strength and power based activities (2–3 repetitions, 3–5 sets, 3–6 days per week depending on frequency of competition) (Plisk and Stone 2003).

Transition/recuperation period/active rest

This period usually lasts around a month, depending on the sport, the stresses of the previous competitive season and the timing of the next one. The aims are to achieve full recuperation in readiness for the general preparation period ahead. This period allows any injuries to heal and a period of rehabilitation to occur so that the athlete is ready to resume full training. It is also a time of relaxation and enjoyment. The stresses of competitive sport are far more than just physical. Athletes need time to un-wind and relax. Rest should be taken from the hard training and competition but athletes must also remain active and partake in activities unrelated to their sport. This helps with weight management but also enables the athlete to maintain a degree of general fitness going into the general preparation phase. The activities should be novel and fresh and not too demanding (low volume: 1–3 repetitions, 1–3 sets, ∼3 days per week) (Plisk and Stone 2003). A similar strategy can be adopted when peaking/tapering for competition.

There are specific goals for each meso-cycle of training (usually completed in the order below) as proposed by Bompa (1999). These phases include:

- Anatomical adaptation – the development of technique and preparation of the musculoskeletal system (including connective tissues) for the heavier loads used in the following stages (these are usually addressed in the general conditioning phase).

- Hypertrophy (strength endurance) – high volume (repetitions of 8–20 at 50–80% –1RM, for 4–6 sets).

- Strength – which can be subdivided into maximal strength (repetitions of 3–6 at 80–90% –1RM, for 4–8 sets), speed strength (repetitions of 8–15 at <70% –1RM, for 3–4 sets) and strength endurance (repetitions of 20–30 at 30–40% –1RM, for 2–3 sets) (Plisk and Stone 2003).

- Power – can be trained via two primary methods; plyometrics and variations of the ‘Olympic lifts’. However, it is worth noting that few athletes ‘naturally’ have the attributes to perform ‘Olympic lifts’ safely and effectively and therefore this needs to be developed in the early stages of training (McGill 2006). It is also important to select the component of the lift that is most suitable for the training goal, for example lower limb biomechanics during the second pull is similar to the mechanics of a vertical jump. During ‘Olympic lifts’ and their variations it is not necessary to use maximal load as Kawamori et al. (2005) showed that lighter loads (50–70% –1RM) resulted in a greater power output due to a higher velocity. Cormie et al. (2007a, 2007b) also demonstrated that when performing activities (such as jump squats) optimal loading, to achieve peak power, is achieved using only body mass, with no additional external resistance.

These phases, but especially the anatomical adaptation phase, need to take into account the ‘laws of strength training’ and the principles of ‘functional training’ (Table 9.3) to ensure that the individual is appropriately conditioned to perform the more intense phases of training that follow. This approach will not only reduce the risk of injury, but also ensure that each phase of training is as productive as possible/intended.

| Laws of Strength Training (Bompa 1999) | Functional Training (McGill 2006) |

| Develop joint flexibility (active ROM) | Develop intra-muscular co-ordination of fibres within a muscle (fast and slow twitch) |

| Develop tendon strength | Develop inter-muscular co-ordination between muscle groups (efficiency of movement) |

| Develop core strength | |

| Develop stabilisers and fixators (balance between agonists and antagonists) | Develop facilitatory and inhibitory reflex pathways (optimal efficiency through the kinetic chain, affected by balance and posture) |

| Train movements not muscles | Motor learning (optimal efficiency of specific movement) |

Differences between sports

The length of the preparation, competition, transition periods and associated meso-cycles, changes from sport to sport and athlete to athlete. For example, a track and field athlete may have two or three key competitions throughout the course of a three-month competitive season. The rest of the year is effectively preparation for these key competitions. In contrast, an English Premiership football team may only have a six- or seven-week preparation period preceding a nine-month competitive season, during which players are expected to compete on a weekly or a twice-weekly basis. Swimmers often have major competitions arranged on 13- or 14-week cycles. Professional boxers may have between three and four fights a year, with their training always geared towards preparation for the next fight. Despite the different conditions encountered during the preparation for these sports, the following general principles still apply. A gradual build-up in volume (and intensity) early on; as the competition approaches the intensity or quality increases further, whilst the volume tapers off.

Application to sports performance

For athletes with limited training experience the incorporation of a periodisation plan provides an excellent framework to develop an athlete’s lifting skills, as well as their strength and power. For example, if an individual wishes to compete in Olympic weight-lifting but has never actually completed a structured resistance training programme, they need to start with the basic components of the ‘Olympic’ lifts, and progress to the point where they are as strong as possible in each of these components, while they learn the complete ‘Olympic’ lifts. Each meso-cycle should teach progressively more complex components of the lifts to ensure correct technique and to allow for the appropriate anatomical and functional adaptations (neuromuscular control, active range of motion, joint stability, tendon strength) to occur until the complete lifts (snatch and clean and jerk) can be performed (Table 9.4). See Appendix 1 and 2 for illustrations of the clean and snatch.

Table 9.4 Example of a macro-cycle 1: weight lifting

By the end of the first macro-cycle, the athlete should be confident/competent at performing each of the primary lifts, but should have also developed a considerable level of strength in the key exercises (back squat, front squat, overhead squat, deadlift, Romanian deadlift, see Figures 9.6–9.10). During the next macro-cycle, the athlete can focus on developing additional strength in each of the key exercises of the individual lifts, while progressively increasing load on the ‘Olympic lifts’. This allows the athlete to perform the primary lifts with additional weight whilst maintaining good technique at high velocities to ensure the development of power.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree