An Evidence-Based Approach to Orthotic and Prosthetic Rehabilitation

Kevin Chui, Rita A. Wong and Michelle M. Lusardi

Learning Objectives

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

3. Efficiently locate meaningful research specific to orthotic and prosthetic rehabilitation.

4. Critically appraise the evidence for validity and clinical importance.

What is evidence-based practice?

Providing effective health and rehabilitative care requires that practitioners be well informed about advances in assessment, medical management, technology, theory, and rehabilitation interventions. Relying on past experience or on the opinion of experts is not enough. An effective health care provider must also regularly update his or her knowledge base by accessing the ever-growing information generated by clinical researchers and their basic science colleagues.1 Providers in all health care disciplines face a number of challenges, however, in efficiently and accurately locating, appraising, and applying scientific evidence in the midst of their increasingly hectic clinical practice schedules.2–4 Health care providers who routinely use such skills and strategies demonstrate an evidence-based approach to patient care. This chapter provides guidance to the practitioner in overcoming these challenges to engaging in evidence-based practice (EBP).

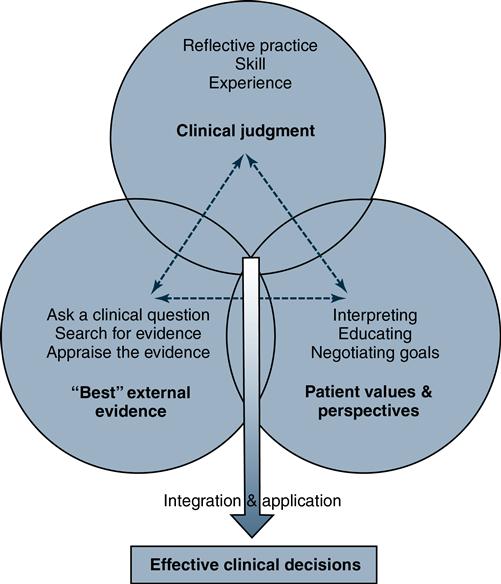

David Sackett, MD, the father of evidence-based medicine, described this approach as the “integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values.”4 EBP is a broader concept that applies Sackett’s physician-oriented concepts to a wide range of health professions.4 Both models identify three major elements of evidence that are interactive and valuable, as well as a set of skills necessary to integrate each resource into an effective and informed clinical decision (Figure 4-1). The three major elements are the following:

1. Best available information from up-to-date, clinically relevant research

3. The integration of the patient’s and family’s issues, concerns, and hopes into the care plan

All three elements are equally important for an effective clinical decision making process; optimal health care outcomes are grounded on integration of perspectives and priorities that each source of information brings to bear.

To make an informed clinical decision, the evidence-based rehabilitation professional must possess the skills to do the following:

1. Effectively search for and access relevant scientific evidence in the professional literature.5

2. Assess the strength and value of the scientific evidence that will support the decision to be made.6

3. Apply results of an accurate clinical examination, as well as the evidence from the literature, in the process of diagnosis, evaluation, prognosis, and development of an appropriate plan of care.7

4. Assess and incorporate the patient’s or client’s values, knowledge, preferences, and motivation into the intervention and anticipated outcomes.8

The process of evidence-based practice

EBP is essentially an orientation to clinical decision making that incorporates the best available sources of evidence into the process of assessment, intervention planning, and evaluation of outcomes. The skill set necessary for effective EBP develops over time, with practice and experience.

An EBP approach to the scientific literature is a systematic process with four primary steps1,4,9:

Step 1: formulating an answerable clinical question

The questions posed by researchers and the questions posed by clinicians, while similar in many respects, are asked and answered at quite different levels. Research questions combine information from groups (samples) of individuals to develop evidence about relationships among characteristics, effectiveness of examination strategies, or effectiveness of intervention strategies for the group as a whole.10 In contrast, clinical questions seek to apply this knowledge to a single person with individual characteristics.4,5,9 For example, clinicians ask, “Which examination strategy will provide the information most important for the clinical decision-making process for this particular individual?” and “Which intervention is likely to have the optimal outcome for this particular individual?”

The first essential step in the EBP process is developing a well-formulated, clinically important question. Sackett identifies two categories of clinical questions: broad background questions and specifically focused foreground questions.4Background questions expand our knowledge or understanding of a disorder, impairment, or functional limitation; they are often concerned with etiology, diagnosis, prognosis, or typical clinical course. Patients and their family members often ask health care practitioners background questions. Answers to background questions expand the general knowledge base used in clinical decision making. Students and novice clinicians ask many background questions as they develop expertise in their field. Even expert clinicians routinely need to seek answers to basic background questions when they encounter an unfamiliar pathology or novel category of intervention. Answers to background questions do not, however, provide the specific evidence necessary to make individualized patient care decisions. Examples of broad background questions that might be asked by clinicians providing prosthetic and orthotic rehabilitation care include the following:

• What is peripheral arterial disease and why can it lead to limb amputation?

• What neurological functions are affected with a C7 spinal cord injury?

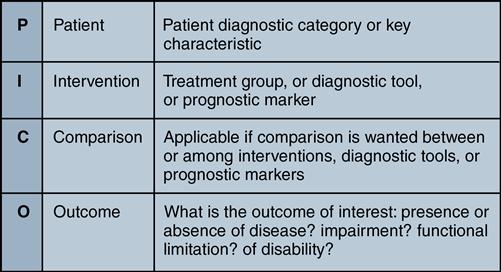

Foreground questions, in contrast, seek specific information to help guide management for an individual patient.4,5,9 The most effective way to frame an answerable foreground clinical question follows the “PICO” model (Figure 4-2). It identifies the patient population of interest (P), noting specific characteristics (e.g., age, gender, diagnosis, acuity, severity) that will link the evidence to the patient care situation prompting the question. It then identifies the predictive factor, examination, or intervention (I) that is being considered. If appropriate, it identifies what comparisons (C) are being made to inform choice of examination or intervention. Finally, it clearly defines the outcomes (O) that might be expected for the given patient on the basis of the best available evidence. Using the PICO model, foreground questions that rehabilitation professionals might ask as they care for a specific individual in need of a prosthesis or orthosis include the following:

Patient Characteristics (P)

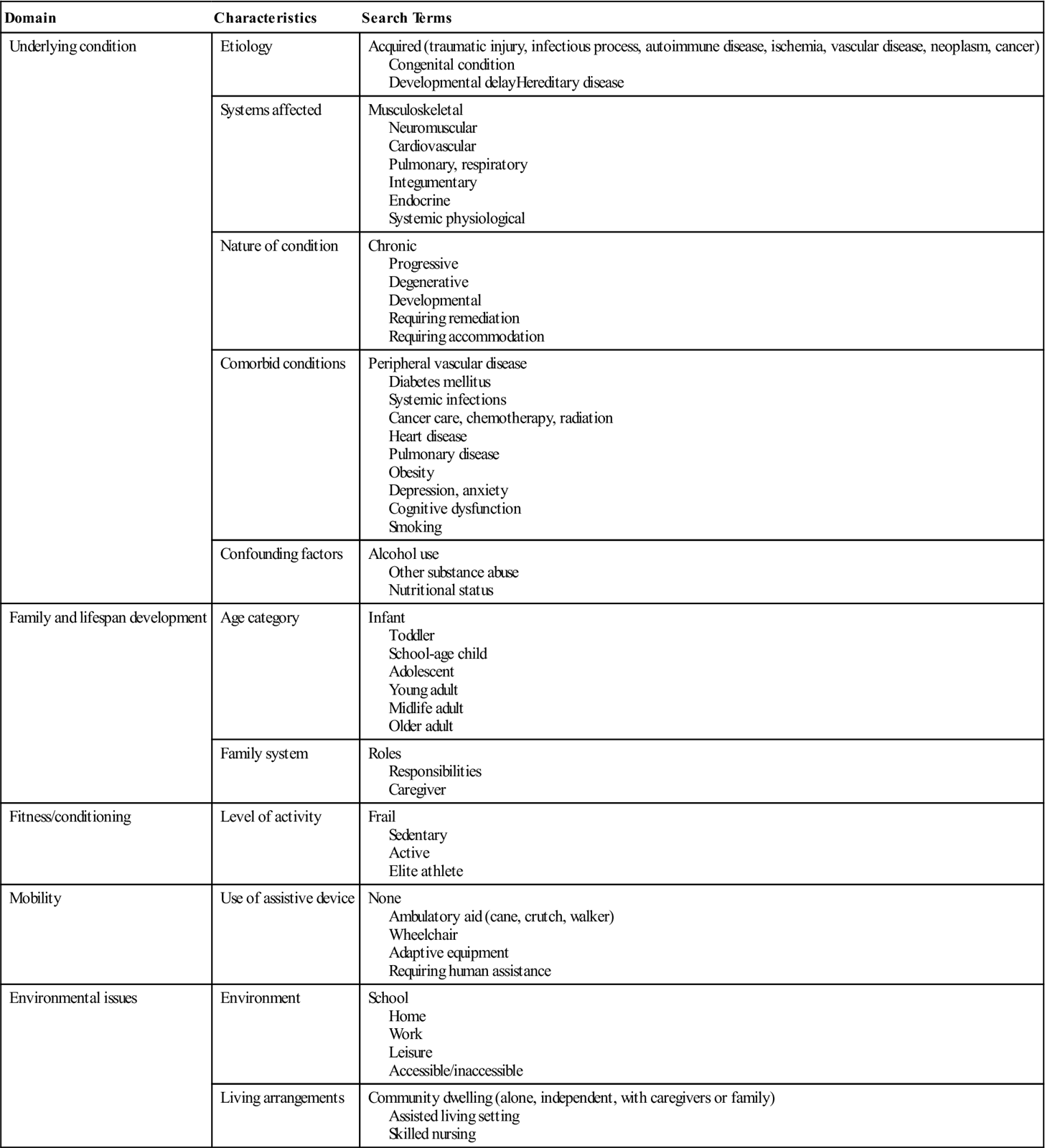

A well-focused clinical question narrows the scope of possible patient characteristics to ones most applicable to a specific clinical problem or situation.4,9 It defines the key characteristics that will best differentially guide the search for evidence. Characteristics or categories that help focus a clinical question related to orthotic or prosthetic management are summarized in Table 4-1.

Table 4-1

| Domain | Characteristics | Search Terms |

| Underlying condition | Etiology | Acquired (traumatic injury, infectious process, autoimmune disease, ischemia, vascular disease, neoplasm, cancer) Congenital condition Developmental delayHereditary disease |

| Systems affected | Musculoskeletal Neuromuscular Cardiovascular Pulmonary, respiratory Integumentary Endocrine Systemic physiological | |

| Nature of condition | Chronic Progressive Degenerative Developmental Requiring remediation Requiring accommodation | |

| Comorbid conditions | Peripheral vascular disease Diabetes mellitus Systemic infections Cancer care, chemotherapy, radiation Heart disease Pulmonary disease Obesity Depression, anxiety Cognitive dysfunction Smoking | |

| Confounding factors | Alcohol use Other substance abuse Nutritional status | |

| Family and lifespan development | Age category | Infant Toddler School-age child Adolescent Young adult Midlife adult Older adult |

| Family system | Roles Responsibilities Caregiver | |

| Fitness/conditioning | Level of activity | Frail Sedentary Active Elite athlete |

| Mobility | Use of assistive device | None Ambulatory aid (cane, crutch, walker) Wheelchair Adaptive equipment Requiring human assistance |

| Environmental issues | Environment | School Home Work Leisure Accessible/inaccessible |

| Living arrangements | Community dwelling (alone, independent, with caregivers or family) Assisted living setting Skilled nursing |

Intervention (I)

The term intervention is used broadly in the evidence-based literature. In the EBP paradigm the intervention (I) and comparison intervention (C), described according to the PICO system, refer to the central issue for which the clinician is seeking an answer. This issue can typically revolve around an intervention, a diagnosis, or a prognosis.

1. Intervention: a procedure or technique (e.g., a physical modality, surgical procedure, medication) (I) that is compared with alternative procedures or techniques (C).11,12

2. Diagnostic test: a test or measure (e.g., a bone mineral density test for identification of osteoporosis; the Berg Balance Scale for identification of fall risk) (I) that correctly differentiates patients with and without a specific condition (C).13,14

3. Prognostic marker: a specific set of characteristics or factors (I) that effectively predicts an outcome (O) for a given patient problem (P).15

Defining the Outcome (O)

A good clinical question focuses on the outcome that is most relevant to the patient care situation at hand. The Nagi model of disablement or the World Health Organization International Classification of Function (ICF) model provide frameworks for clinicians to define the outcome they are most interested in: pathology or disease at the cellular level, impairment of a physiological system, functional limitation at the level of the individual, or disability or handicap that interferes with the normal social role16,17 (see Figure 1-3).

Step 2: locating and accessing the best evidence

Once the clinical question has been clearly identified and articulated, the next step is to search the rehabilitation research literature for relevant information. The second step is to access full text articles, access their quality, and read those might that inform decision making.18–21Among the many ways to find citations and (hopefully) the full text of the article are the following:

• Regularly visit key journal websites to review what has been recently published or published ahead of print that might be relevant to the question. The Journal of Prosthetics and Orthotics (http://www.oandp.org/jpo), for example, allows full access to any journal article published in the years previous to the current year. This strategy can be somewhat “hit or miss” in terms of effectiveness.

• Use an Internet search engine such as Google.scholar (http://scholar.google.com; free access), which provides both unjuried and juried resources and requires the ability to carefully assess the quality of the source and of the information that has been located.

• Use electronic databases of peer-reviewed journals such as PubMed/Medline/OVID (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed; free access), or the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro; http://www.pedro.org.au/; free access) using appropriate key words. Professional organizations such as the American Physical Therapy Association provide links to search engines (http://www.apta.org/OpenDoor), abstracted article reviews (http://www.hookedonevidence.org) or synthesized evidence (http://www.apta.org/PTNow) for organization members. Many medical libraries maintain subscriptions to multiple medical databases through services such as EBSCO (http://www.ebscohost.com/biomedical-libraries; subscription access) or ProQuest (http://www.proquest.com/en-US/catalogs/databases/detail/pq_health_med_comp.shtml), among others.

• Subscribe to online Table of Content (eTOC) alerts from research journals relevant to their practice areas. For example, the Physical Therapy Journal (http://ptjournal.apta.org/site/subscriptions/etoc.xhtml), the Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy (www.jgpt.org), the Journal of Neurologic Physical (www.jnpt.org), Clinical Biomechanics (http://www.clinbiomech.com/user/alerts), and the Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (http://www.archives-pmr.org/user/alerts/savetocalert), among many others will send table of contents for current issues to email, cell phone, iPads, e-readers, and other devices.

Each strategy has pros and cons in terms of efficiency and availability. Health professionals who use an evidence-based approach to patient care develop, over time, an information seeking strategy that works within their time constraints and accessible resources.22–24

Sources of Evidence

Clinicians can access information from the research literature in a variety of formats and from a variety of sources. One of the most accessible formats is a journal article.25,26Table 4-2 provides a list of the journals particularly relevant to orthotic and prosthetic rehabilitation. These journals often contain original clinical research, reviews of the literature, and case reports focused on issues most relevant to the particular professional group.

Table 4-2

Journals Relevant to Orthotic and Prosthetic Rehabilitation

| Journal Title | Abbreviation |

| American Journal of Occupational Therapy | Am J Occup Ther |

| American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation | Am J Phys Med Rehabil |

| American Journal of Podiatric Medicine | Am J Podiatr Med |

| American Journal of Surgery | Am J Surg |

| American Rehabilitation | Am Rehabil |

| Annals of Physical Medicine | Ann Phys Med |

| Archives of Neurology | Arch Neurol |

| Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation | Arch Phys Med Rehabil |

| Archives of Surgery | Arch Surg |

| Assistive Technology | Assist Tech |

| Athletic Training | Athletic Training |

| Australian Journal of Physical Therapy | Aust J Physiother |

| Biomechanics | Biomechanics |

| British Journal of Sports Medicine | Br J Sports Med |

| Bulletin of Prosthetic Research | Bull Prosthet Res |

| Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy | Can J Occup Ther |

| Clinical Biomechanics | Clin Biomech |

| Clinics in Orthopedics and Related Research | Clin Orthop Rel Res |

| Clinics in Podiatric Medicine and Surgery | Clin Podiatr Med Surg |

| Clinics in Prosthetics and Orthotics | Clin Prosthet Orthot |

| Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology | Dev Med Child Neurol |

| Diabetes Care | Diabetes Care |

| Diabetic Foot | Diabe Foot |

| Diabetic Medicine | Diabe Med |

| Disability and Rehabilitation | Disabil Rehabil |

| Foot and Ankle Clinics | Foot Ankle Clin |

| Foot and Ankle International | Foot Ankle Int |

| Gait and Posture | Gait Posture |

| Interdisciplinary Science Reviews | Interdisc Sci Rev |

| International Journal of Rehabilitation Research | Int J Rehabil Res |

| Journal of Allied Health | J Allied Health |

| Journal of Applied Biomechanics | J Appl Biomech |

| Journal of Biomechanical Engineering | J Biomech Eng |

| Journal of Biomechanics | J Biomech |

| Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery | J Bone Joint Surg |

| Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy | J Geriatr Phys Ther |

| Journal of Head Trauma and Rehabilitation | J Head Trauma Rehabil |

| Journal of Medical Engineering and Technology | J Med Eng Tech |

| Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine | J Musculoskel Med |

| Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy | J Neuro Phys Ther |

| Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy | J Orthop Sports Phys Ther |

| Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics | J Pediatr Orthop |

| Journal of Prosthetics and Orthotics | J Prosthet Orthot |

| Journal of Rehabilitation | J Rehabil |

| Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine | J Rehabil Med |

| Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development | J Rehabil Res Dev |

| Journal of Spinal Disorders | J Spinal Disord |

| Journal of the American Geriatrics Society | J Am Geriatr Soc |

| Journal of the American Medical Association | JAMA |

| Journal of the American Podiatry Association | J Am Podiatry Assoc |

| Journal of Trauma | J Trauma |

| Medical and Biological Engineering | Med Biol Eng Comp |

| Orthopedic Clinics of North America | Orthop Clin North Am |

| Paraplegia | Paraplegia |

| Physiotherapy Canada | Physiother Can |

| Physical and Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics | Phys Occup Ther Geriatr |

| Physical and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics | Phys Occup Ther Pediatr |

| Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation Clinics of North America | Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am |

| Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation: State of the Art Reviews | Phys Med Rehabil State Art Rev |

| Physical Therapy | Phys Ther |

| Physiotherapy | Physiotherapy |

| Physiotherapy Research International | Physiother Res Int |

| Prosthetics and Orthotics International | Prosthet Orthot Int |

| Rehabilitation Nursing | Rehabil Nurs |

| Rehabilitation Psychology | Rehabil Psychol |

| Scandinavian Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine | Scand J Rehabil Med |

| Spinal Cord | Spinal Cord |

| Spine | Spine |

| Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation | Top Stroke Rehabil |

The medical literature is divided into primary and secondary sources of information. Primary sources are the reports of original scientific work, commonly published as journal articles. Secondary sources are summary reviews of the primary literature on given topics. Secondary sources include textbooks, review articles, systematic reviews such as meta-analyses, critical reviews of individual articles, clinical practice guidelines, and website summaries. Research studies are the foundation of meaningful evidence. Academic textbooks, biomedical journals, and Internet websites aimed at health professionals and biomedical researchers are common sources of research evidence.

Textbooks

Academic textbooks can be a good starting point for locating background information, particularly for content areas that change slowly (e.g., gross anatomy or biomechanics). Evidence-based textbooks are well referenced, go through a review process, and are typically updated every 3 to 5 years. They summarize clinical studies and opinions of experts, and analyze/synthesize the impact of the research and expert opinion on the topic. Some textbooks are now available online, which provides the advantage of frequent updating of specific sections as new research evidence emerges and allows the reader to immediately hyperlink to primary research article sources. The website FreeBooks4Doctors! (www.freebooks4doctors.com) provides hyperlinks to many key medical textbooks free of charge online. Many other online textbooks are available for purchase. Box 4-1 lists key indicators of quality in academic textbooks.

Primary Sources: Journal Articles

Journal articles may serve as either primary or secondary literature sources. They can be useful for both background and foreground clinical questions. Primary research articles are those in which the author presents the findings of a specific original study.27,28 It is best to use this category of evidence when dealing with rapidly evolving areas of health care (which many clinical practice questions fall into). Identifying two or three high-quality primary research articles that, in general, provide similar supporting evidence offers strong evidence on which to base a clinical decision. Searching, critiquing, and synthesizing primary research sources is a time-intensive task.

Secondary Sources: Integrative and Systematic Review Articles

Use of high-quality secondary source journal articles to guide evidence-based determinations can be a time-efficient strategy for clinicians.29,30 Quality indicators for secondary source articles include a comprehensive search of the literature (using an explicit search strategy) to identify existing studies, an unbiased analysis of these studies, and objective conclusions and recommendations on the basis of the analysis and synthesis.31 Secondary sources are available in a variety of formats: integrative narrative review, systematic review, meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline (CPG). Each of these summative resources can be an effective and time-efficient method to obtain a critical assessment of a specific body of knowledge. However, there are benefits and drawbacks associated with each type of summative resource.

In an integrative review article the author reviews and summarizes, and sometimes analyzes or synthesizes, the work of a number of primary authors.32 These narrative reviews are often broad in scope, may or may not describe how articles were chosen for inclusion in the review, and present a qualitative analysis of previous research findings. The quality (validity) of the narrative review varies with the expertise of the reviewer and requires careful assessment by the reader.

Systematic reviews are particularly powerful secondary sources of evidence that typically analyze and synthesize controlled clinical trials.29,31,33 Well-done systematic reviews are valuable sources of evidence and should always be sought when initiating a search. Box 4-2 lists key indicators of a quality systematic review. Systematic reviews are typically focused on a fairly narrow clinical question, are based on a comprehensive search of relevant literature, and use well-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria to select high-quality studies (typically randomized controlled trials) for inclusion in the review. Each study included in the review is carefully appraised for quality and relevance to the specific clinical topic. The author attempts to identify commonalities among study methods and outcomes, as well as account for differences in approaches and findings. A good systematic review is labor intensive to prepare; thus only about 1.5% of all journal articles referenced in Medline are true systematic reviews.34 Although the numbers are low, increasing numbers of systematic reviews are being published, including ones on topics relevant to orthotics and prosthetics. For example, a PubMed search from 2006 to July 2011 of the literature using the terms “limb amputation AND rehabilitation” combining the limits (a) review and (b) English yielded 49 applicable reviews (Appendix 4-1).

A meta-analysis is a type of systematic review that quantitatively aggregates outcome data from multiple studies to analyze treatment effects (typically using the “odds ratio” statistic) as if the data represented one large sample (thus with greater statistics power) rather than multiple small samples of individuals.29,31,35 The limitation to performing a meta-analysis is that, in order to combine studies, the category of patients, the interventions, and the outcome measures across the studies must all be similar. Meta-analyses can provide more powerful statements of the strength of the evidence either supporting or refuting a given treatment effect than the separate assessment of each study. Because of the difficulty in identifying studies with enough similarity to combine data, only a small subset of systematic reviews have been carried to the level of a meta-analysis. One meta-analysis was identified in PubMed using the terms “limb amputation AND rehabilitation” combined the limits a) meta-analysis, b) English, and c) published in last 5 years.36

Secondary Sources: Clinical Practice Guidelines

Another secondary resource for clinicians may be CPGs that have been developed for application to clinical practice on the basis of the best available current evidence.37 Most existing CPGs have been developed for screening, diagnosis, and intervention in medical practice. CPGs are intended to direct clinical decision making about appropriate health care for specific diseases among specific populations of patients. The best available evidence upon which CPGs are typically based combines expert consensus and review of clinical research literature.38 Most are interpreted as prescriptive, using algorithms to assist decision making for appropriate examination and intervention strategies for patients with given characteristics. Examples of CPGs that may be relevant to orthotic and prosthetic rehabilitation are listed in Appendix 4-2. The National Guidelines Clearinghouse is the most comprehensive database in the United States for CPGs (www.guidelines.gov).

Electronic Resources and Search Strategies

A number of electronic databases can assist clinicians in quickly locating primary and secondary sources of evidence to guide clinical decision making (Table 4-3). When seeking articles, it is often helpful to use several different databases. The American Physical Therapy Association provides access to many electronic resources described below as a service to APTA members via its Open Door portal on the website www.APTA.org.

Table 4-3

Electronic Databases Used to Search for Relevant Evidence

| Acronym | Database Information | Access |

| — | Academic Search Premier | By library access |

| Best Evidence | ACP Journal Club and Evidence Based Medicine (critical and systematic reviews) | http://hiru.mcmaster.ca/acpjc/acpod.htm |

| CCTR | Cochrane Controlled Trials Register | By subscription or library access |

| CDSR | Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | By subscription or library access |

| CHID | Combined Health Information Data Base (titles, abstracts, resources, program descriptions not indexed elsewhere) | www.chid.nih.gov |

| CINAHL | Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (citations and abstracts) | By subscription or library access (www.cinahl.com) |

| DARE | Cochrane Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness | By subscription or library access |

| EBM Online | Evidence-based Medicine for Primary Care and Internal Medicine (critical reviews and systematic reviews) | By subscription (www.ebm.bmjjournals.com) |

| Embase | Embase/Elsevier Science (Citations and abstracts) | By subscription (www.embase.com) |

| — | Hooked on Evidence/American Physical Therapy Association (citations, abstracts, annotations) | By membership in American Physical Therapy Association (www.apta.org) |

| Medline | National Library of Medicine (abstracts) | By library access |

| OVID | A collection of health and medical subject databases (abstracts and full text) | By subscription or library access (www.gateway.ovid.com) |

| PEDro | The Physiotherapy Evidence Database (systematic reviews) | www.pedro.fhs.usyd.edu.au/index.html |

| PubMed | National Library of Medicine (abstracts) | www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez (no charge) |

Using an electronic database effectively is a two-step process. First, the searcher must locate applicable citations that provide the title of the article, author, and other key identifying information (e.g., journal, issue, year, pages). Most often, these citations also provide an abstract of the article. Sometimes the searcher can gather enough information about the applicability of the article for his or her needs purely on the basis of the information found in the title and abstract. Most often, however, the searcher must access the full-text article in order to adequately assess the findings of the study. Citations and abstracts are readily available free of charge from numerous databases. However, access to the full text of articles often requires a paid subscription to search databases.

Locating Citations

The National Library of Medicine, through the database PubMed, produces and maintains Medline, the largest publicly available database of English language biomedical references in the world. PubMed references more than 4600 journals including many key non–English language biomedical journals. These journals, in the aggregate, include more than 15 million individual journal article citations. This database is also a rich source of citations for quality systematic reviews. Journals indexed in PubMed must meet rigorous standards for their level of peer review and the quality of the articles published in the journal; this gives the searcher some confidence in the information that is located through PubMed. PubMed can be accessed through the National Library of Medicine’s website (www.nlm.nih.gov). OVID is another Medline resource; it is typically accessed via library subscription and often links full text articles.

The Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) includes journal citations from a larger pool of nursing and allied health fields than is found in Medline. Many of these journals have a much smaller circulation than the typical Medline cited journals, and the quality of these smaller circulation journals may not meet PubMed requirements. Thus the reader must be aware that closer scrutiny of validity and methodological quality may be necessary. However, the greater inclusion of rehabilitation-focused journals in the CINAHL database makes this an important database for rehabilitation professionals. This database is only available to paid subscribers (library or individual subscriptions).

Hooked on Evidence is a database of the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) and is available free of charge to members of the association (www.hookedonevidence.com). Presently Hooked on Evidence consists of primary intervention studies only. Articles in Hooked on Evidence have been reviewed and abstracted by physical therapy academicians and researchers, graduate students, and clinicians. These abstracts may be sought by selecting a practice pattern group, condition, and clinical scenario.

PEDro is a database of the Centre for Evidence-based Physiotherapy at the University of Sydney, Australia, and is available to the public free of charge (www.pedro.org.au). PEDro lists clinical practice guidelines, systematic reviews, and clinical trials. An advanced search allows the searcher to select the type of therapy, problem, body part, and subdiscipline. Both the Hooked on Evidence and PEDro databases focus exclusively on high-quality studies related to physical therapy. Their benefit is ease of identifying citations applicable to physical therapy and rehabilitation. To search either database successfully, the research question should be fairly broad, using synonyms that represent words in the title. Both databases contain only a fraction of the citations found in PubMed; all of the citations, however, are directly applicable to rehabilitation. A search of PEDro using “orthoses” identified one practice guideline, 23 systematic reviews, and 26 clinical trials, all relevant to physical therapy (Appendix 4-3). A similar search in Hooked on Evidence found 77 reviews of clinical trials, 29 of which were published since 2006 (Appendix 4-4).

The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (www.cochrane.org/cochrane-reviews) is widely accepted as the gold standard for systematic reviews. Groups of experts perform comprehensive and quantitative analysis and synthesis of the existing research on well-focused topics and distill the findings into scientifically supported recommendations. Cochrane reviews use a standardized format and carefully follow rules to decrease bias in the choice of articles to review and in the interpretation of the evidence. Although few address physical therapy exclusively, rehabilitation procedures and approaches are a component of many of these reviews. The findings are reported in structured abstracts that summarize the key aspects of the full review including the authors’ conclusions about the strength of the evidence and their recommendations. These structured abstracts are available free online. Access to full-text review articles requires a paid subscription, however.

Finding valuable secondary references on the web is increasingly possible. However, searchers must carefully scrutinize these materials as there is wide variability in accuracy and objectivity of the published information.39 This evidence represents such varied sources as reports of original research, research reviews from trusted experts, student summaries that are non–peer reviewed, marketing advertisements (sometimes presented visually to appear to be a peer-reviewed research report), and lobbying groups’ perspectives and persuasive arguments. There are many patient-focused sites and fewer practitioner-focused ones. The quality indicators identified in Table 4-2 are applicable to Internet websites as well as textbooks.

Executing Search Strategies

Often, the first search for citations results in one of two extremes: hundreds or thousands of citations, with only a few related to the clinical question being asked, or almost no citations focused on the topic of interest.18,40,41 Searchers should look carefully at the citations that result from a search. In the search that is too broad, the searcher must examine closely what he or she is really looking for, comparing titles and key words that have resulted from the search. Often, the search is repeated, by rewording or setting limiters to narrow results and omit the previously identified unrelated citations. A searcher who uses the search term prosthesis may find that the results the search include articles about such diverse topics as joint prostheses, dental prostheses, and skin prostheses, as well as limb prostheses. Search terms should be as applicable to the specific clinical question being posed as possible; using more precise search terms such as limb prosthesis, leg prosthesis, arm prosthesis, or artificial limb may be more effective.

Searchers should recognize that the search engine is simply matching the search words that the searcher has entered with subject headings linked to the article by the database administrator or librarian using predefined medical subject heading names or words included in the title or abstract. Searchers may need to adjust search terms to find applicable references. For example, a PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/) search of the English language literature published in the past 5 years (between July 2006 and July 2011) using the search terms below-knee amputation combined with the search term prosthetic rehabilitation yielded five citations. The same search using the term transtibial amputation rather than below–knee amputation yielded 45 citations, with no overlap between the two sets of citations. A third search using the term trans-tibial amputation in place of transtibial amputation yielded 12 citations, none of which overlapped with the first search and one that overlapped with the second search.

A search can be unforgiving to misspellings or, as described earlier, slight differences in search terms. If the searcher finds one citation that is on target for the topic of interest, repeating the search using terms from that article’s title or abstract, as well as subject headings (key words), may yield additional appropriate citations. Using a variety of synonyms or Medical Subject Headings (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh) when repeating the search can help the searcher be more confident that the correct concepts are being targeted. Searchers should note the search terms that result in successful searches so that future searches can be most efficient. Searchers using PubMed can set up a permanent search by establishing a “cubby.” This service is free and fully available via Internet connection to PubMed. Online directions help users set up cubbies that save search terms. Searchers can periodically check their cubbies and ask for literature updates on the topic.

In addition to the search topic, a good clinical question will often focus on one of three broad categories of clinical questions: treatment/intervention/therapy, diagnosis, or prognosis.42 Searchers can use these terms to narrow their search as needed. Searchers must recognize that each database uses its own set of key words and may (or may not) include the title words, abstract words, or common sense clinical terms in their electronic search process. Familiarity with key headings used by the database can minimize frustration during the search process; combining words from the title or abstract (e.g., by using Boolean operators such as “AND,” “OR,” or “NOT”), as well as using synonyms for the clinical terms or concepts of interest, can also assist the search process. In many databases, searchers can choose to limit the search to systematic reviews addressing their topic of interest.

Searching for Interventions

Words that are likely to limit the search to studies that focus on interventions include the following43:

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree