Chapter 136 American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Guidelines

Background

Orthopedic surgeons who perform total knee arthroplasty have been greatly affected by the ACCP guidelines for the prevention of deep vein thrombosis. The ACCP is an organization of over 16,500 members who provide clinical respiratory, sleep, critical care, and cardiothoracic patient care. Their venous thromboembolism guidelines first appeared in 1986, and the most recent eighth edition was published in June 2008.6 The SCIP guidelines are essentially based on the 2004 ACCP guidelines. Deep venous thrombosis, detected by venography or ultrasonography, was the primary outcome measure in the development of these guidelines. The strongest recommendations are based on a review of only prospective randomized studies, with most of these comparing the efficacy of one pharmacologic agent with another or a placebo. Few studies were related to mechanical or multimodal (combined) prophylaxis. Surgical patients are grouped as low, medium, or high risk, but all total knee arthroplasty patients are considered high risk, despite patient age, activity level, or comorbidities. Several orthopedic surgeons have voiced concerns with these guidelines, which emphasize prophylaxis with strong pharmacologic agents.2 Asymptomatic thrombi, detected by venography or ultrasonography, are considered as important an outcome as symptomatic thromboembolism. These guidelines may not be applicable to the wide spectrum of patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty and seem to underestimate the risks of bleeding complications and other adverse outcomes, such as prolonged wound drainage or deep infection, related to the use of pharmacologic anticoagulants.

Symptomatic pulmonary embolism is relatively rare after total knee arthroplasty. The 90-day rate of fatal pulmonary embolism was 0.15% after 27,000 total knee arthroplasties in the Scottish Registry.8 In a review of over 200,000 total knee arthroplasties in a California database, the 90-day rate of symptomatic pulmonary embolism was 0.41%.13

The risk of serious bleeding complications has been described in a nonselected group of total hip and knee arthroplasty patients given the ACCP 1A level recommended 10-day course of low-molecular-weight heparin.1 In this study of 290 patients, major bleeding occurred in 9% of patients, with 4.7% requiring readmission. Efficacy of this protocol was also questioned, because symptomatic deep vein thrombosis occurred in 3.8% and nonfatal symptomatic pulmonary embolism occurred in 1.3%. In another cohort study of 263 patients who had total knee arthroplasty, bleeding complications occurred in 4.6% of patients given warfarin (prothrombin time [PT], 1.5 to 2 times control) compared with 11.3% of patients given enoxaparin, with no difference in efficacy.14 A recent study has shown that patients who return to the operating room within 30 days after total knee arthroplasty for evacuation of a postoperative hematoma are at significantly increased risk for the development of deep infection or other major surgery.5

Rationale and Methodology

The primary concerns of orthopedic surgeons after total knee arthroplasty are the prevention of fatal and nonfatal symptomatic pulmonary embolism and minimizing serious joint bleeding and wound drainage that adversely affect the patient’s outcome. The AAOS formed a working group in 2006 to develop a consensus guideline for the prevention of symptomatic pulmonary embolism after total hip and total knee arthroplasty.7,9,10 The working group was composed of eight members of the AAOS with known expertise in the field. The group consulted an evidence review team from the Center for Clinical Evidence Synthesis at Tufts–New England Medical Center, which has assisted other medical specialty groups with the development of guidelines. The key goals or questions were to determine the rates of fatal and symptomatic pulmonary embolism after total hip and knee arthroplasty with several interventions (e.g., aspirin, warfarin, low-molecular-weight heparins, pentasaccharides, and mechanical methods) and the rates of adverse events (e.g., bleeding, death) associated with these interventions. The evidence base, determined by a consensus of the working group, was a review of the literature that met certain strict criteria: a prospective study of hip or knee arthroplasties performed since 1996 only; a cohort study with at least 100 patients per group; or a randomized controlled trial with at least 10 patients per treatment group.10 There were no recent studies of the natural history (pulmonary embolism without prophylaxis) that included at least 1000 patients. Older studies were excluded because the consensus of the working group was that techniques and postoperative rehabilitation had greatly changed in more recent times.

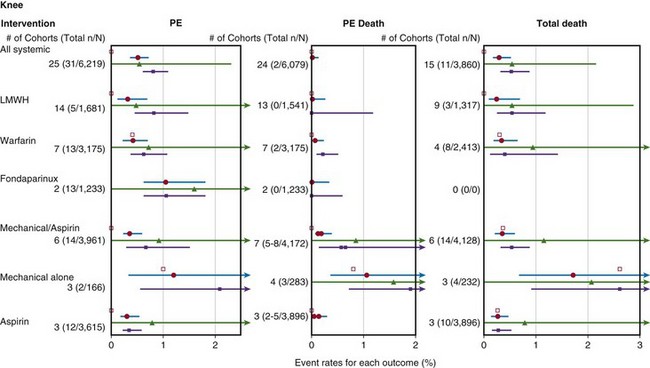

The literature review included 2713 citations from search engines and 10 other articles that the working group was aware of but had not been retrieved.10 Of these 2723 citations, only 42 articles met the previously specified criteria of the working group. Of the 42 articles, 16 articles, with cohorts totaling 11,665 total knee arthroplasties were reviewed by the evidence review team. The individual studies were graded according to levels of evidence (I to V). The strength of recommendation was graded on the basis of the quality of the collection of studies from which the recommendation was derived (A to D). Of the 15 total knee studies (9939 patients) summarized in the Forest plot, 10 were considered fair quality and 5 were considered poor quality (Fig. 136-1). The findings of only one total knee study, in which patients with a history of thromboembolism were not excluded, had wide applicability, eight had moderate applicability, and six had narrow applicability. The reviewed studies were heterogeneous in a number of areas, including treatment doses, intensity and timing, cotreatments, and anesthetic techniques.

Figure 136-1 Event rates of pulmonary embolism (PE) after total knee arthroplasty in the reviewed studies. nd, no data.

(From Lachiewicz PF: Prevention of symptomatic pulmonary embolism in patients undergoing total hip and knee arthroplasty: clinical guideline of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Instr Course Lect 58:795–804, 2009.)

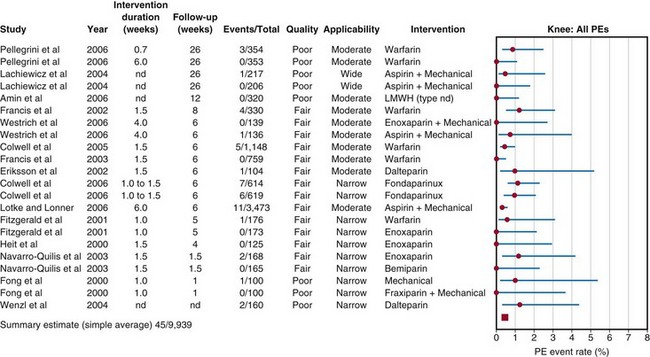

The results of the literature review were presented as separate Forest plots for total hip and knee arthroplasty and included the following: all pulmonary embolism after total knee arthroplasty (see Fig. 136-1); any pulmonary embolism, fatal pulmonary embolism, and all deaths after total knee arthroplasty (Fig. 136-2); and major bleeding and death related to bleeding after total knee arthroplasty (Fig. 136-3).Conclusions from the literature review of both total hip and total knee arthroplasty patients were described together. The rate of fatal pulmonary embolism was approximately 1/1700 arthroplasties, and there was no difference among prophylactic methods. The rate of nonfatal pulmonary embolism was approximately 1/300 arthroplasties with any prophylactic method. The rate of death from bleeding was approximately 1/3000 arthroplasties. Major bleeding complications were more common in patients treated with systemic pharmacologic prophylaxis (random effects model [REM] summary estimate, 1.8%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.4% to 2.5%) than in those treated with mechanical prophylaxis and aspirin (REM summary estimate, 0.14%; 95% CI, 0.03% to 0.8%). There were numerous limitations of the literature review including clinical heterogeneity, outcome measures, and sample sizes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree