Advanced Techniques and Frontiers in Hip Arthroscopy

Marc J. Philippon

Bruno G. Schroder e Souza

Karen K. Briggs

Hip arthroscopy is a fast evolving field in orthopedic surgery. The past decade consisted on a period in which new applications and safer techniques were developed, and more people started their experience with this procedure. In the past 10 years, the procedure has gained interest with the “rediscovery” of femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) (1), and the development of arthroscopic techniques to treat that condition (2).

Performing a fast search on Medline through PubMed using the term “hip arthroscopy,” one will find that 234 papers have been published on that topic to date. Of these papers, 137 were published in the past 5 years. For the search of the “femoroacetabular impingement,” which is currently the main indication for hip arthroscopy, 175 papers were found being more than half (81) were published in the past 2 years. The objective of this chapter is to present and discuss advanced techniques in hip arthroscopy that are currently in use, as well as new techniques that are on the new frontier of hip arthroscopy.

MODERN SURGICAL SETUP AND PORTAL PLACEMENT

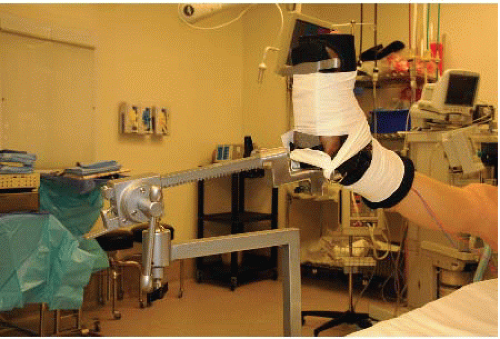

Arthroscopy of the hip can be performed in a lateral or supine position. Our preference is the modified supine approach (2). We recommend a combination of general anesthesia with a lumbar plexus sciatic regional block, for complete muscular paralysis. After the induction of anesthesia, the patient is positioned on a standard fracture table that allows independent lower extremity traction. The perineum is positioned against a large, padded bolster with care taken to protect the genitalia. The feet are placed in padded boots that are secured with Velcro straps and reinforced with a tape wrap (Fig. 51.1). Both legs are positioned in 40° of abduction, 20° of flexion, and neutral rotation.

Gentle traction is applied through the operative hip with moderate countertraction through the nonoperative hip as needed. A lateral tilt of the table of 10° to the contralateral side is obtained to optimize traction forces. Fluoroscopy is used to obtain an anteroposterior (AP) view of the operative hip. The fluoroscopic image should be observed for distraction of the joint space as well as the development of a “vacuum sign” or radiolucency within the joint space. Once the vacuum sign has been visualized, the operative leg is adducted to neutral. The foot is maximally internally rotated, bringing the femoral neck parallel to the floor (about 15°). Joint distraction is assessed with fluoroscopy, and additional traction is applied to restore the vacuum sign. Approximately 8 to 10 mm of distraction should be obtained between the acetabulum and femoral head to provide instrument clearance and to avoid iatrogenic damage to the labrum or chondral surfaces. The time of traction application is noted, and continuous traction time is limited to less than 2 hours.

We currently use the anterolateral and the distal lateral accessory portal in most cases. The anterolateral portal is placed approximately 1 to 2 cm superior to the tip of the greater trochanter and 1 to 2 cm anterior from this proximal point. The needle is guided slightly cephalic and posterior to converge along the direction of the femoral neck, at an angle of approximately 15° to 20° in relation to the floor. After capsular penetration, a tactile decrease in the resistance indicates the labrum has not been pierced. Fluoroscopic images may be obtained to reassure the position of the needle. The injection of 30 mL of saline helps to distend the joint and the liquid rebound confirm its intra-articular position. A 70° arthroscope is introduced into the joint with fluid pump set at 50 mm Hg of pressure and at high flow. Once within the joint, one should be able to visualize the femoral head and acetabulum. Additional traction may be applied as needed to allow improved instrument mobility within the joint.

INTRA-ARTICULAR PROCEDURES

Current Approach to FAI

The diagnosis of FAI has recently been clinically described in several publications. Patients with bony deformities causing FAI and pain should be effectively treated. Conservative measures have not shown to be effective when intra-articular lesions are present. Therefore, surgical

treatment should be considered the gold standard for those patients. We prefer the arthroscopic approach because it is effective and allows for faster recovery (3).

treatment should be considered the gold standard for those patients. We prefer the arthroscopic approach because it is effective and allows for faster recovery (3).

Acetabular Rim Trimming

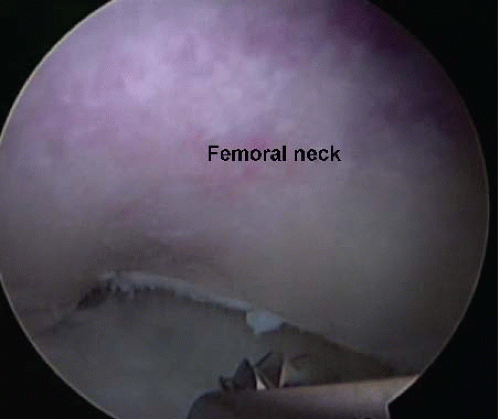

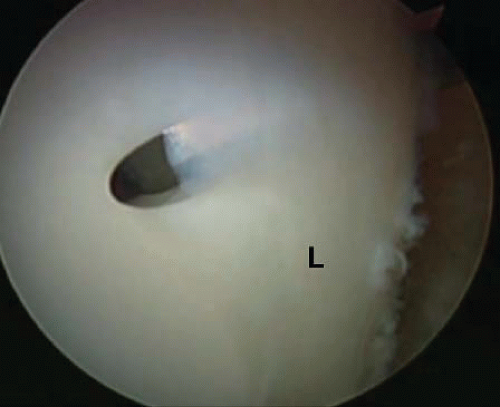

In case of labral detachment at its base, which is particularly common in cases with associated cam impingement, the labrum should be separated in the watershed zone so that underling bone deformity can be corrected, and the labrum reattached with suture anchors. That is achieved by a systematic approach. First, we delineate the chondrolabral junction by controlled application of a monopolar radiofrequency chisel. This will contract the fibrocartilage and better define the tear, preventing sacrifice of healthy labral tissue as well as stabilize that adjacent acetabular cartilage. Chondral flaps are removed after demarcation with aid of the same RF device. The area between the labrum and the capsule is then dissected with a shaver, and the labrum is completely detached from the acetabular rim (Fig. 51.2). The acetabular bony overhang, responsible for the pincer deformity, is removed with a motorized burr before complete labral detachment and after detachment, depending on the amount of resection required (Fig. 51.3). That amount should be estimated preoperatively by the analysis of preoperative images. There is a correlation between the center-edge angle and the amount of lateral resection in millimeters. The formula CE angle reduction = 1.8 + (0.64 × rim reduction in millimeters) was obtained in a prospective study and provides a good parameter for the resection (4). The resection should never diminish the center-edge angle to less than 25°. The working portal to perform most of the resection is the lateral portal, although switching portals is essential for the assessment of a complete work.

FIGURE 51.2. The labrum (L) is completely detached from the acetabular rim using a beaver blade. Care should be taken not to completely cut through the labrum. |

Femoral Osteoplasty (Cam Resection)

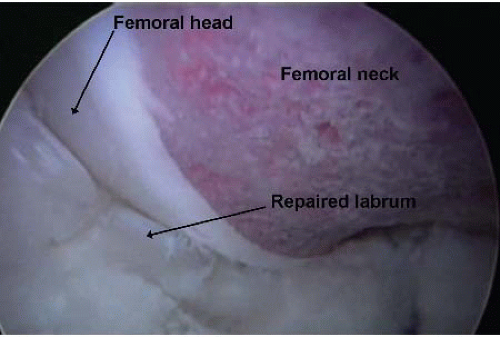

It is important to note that isolated pincer lesions occur in only 10.7% of the cases (5). In most cases, femoral deformities coexist and should be addressed, under risk of failure of the treatment. To approach the peripheral compartment, the traction should be released. As the traction is released and the hip is flexed, we look outside our capsulotomy and enlarge it distally to provide better visualization. In some cases, the zona orbicularis may be very tight and an additional incision starting at the medial aspect of the capsulotomy running distally in the direction of the femoral neck, may be necessary. After inspection of the femoral deformity, the femoral head-neck junction is reshaped. We resect the most prominent part of the deformity and progress until we get visual appraisal of sufficient resection (Fig. 51.4). In some cases, a thin osteotome may be necessary to remove medial osteophytes in the femoral head. The adequacy of the osteoplasty is confirmed by dynamic evaluation of the joint under direct arthroscopic visualization (Fig. 51.5). Any signs of impingement require further bone reshaping or labral contouring. The need of more anchors is commonly noted at this time of the surgery, and we proceed to provide better attachment to

the labrum. In athletes, we reproduce the sports gesture to disclose any potential conflict between the femur and the labrum. Further resection is performed as deemed. The objective is to obtain maximum range of motion without impingement. Dynamic fluoroscopy may aid to determine adequacy of bone resection, but, in our opinion, it is not a substitute for direct arthroscopic inspection. The capsule is then closed, which we find important to resume rehabilitation and prevent instability and finish the procedure.

the labrum. In athletes, we reproduce the sports gesture to disclose any potential conflict between the femur and the labrum. Further resection is performed as deemed. The objective is to obtain maximum range of motion without impingement. Dynamic fluoroscopy may aid to determine adequacy of bone resection, but, in our opinion, it is not a substitute for direct arthroscopic inspection. The capsule is then closed, which we find important to resume rehabilitation and prevent instability and finish the procedure.

FIGURE 51.5. With dynamic evaluation of the joint, the adequacy of the osteoplasty can be assessed. Any bony prominence that causes displacement or movement of the labrum should be resected. |

Some studies have shown that bone resection in the femur is not sufficient in some cases (6). The main reasons for revision surgery in hip arthroscopy are nontreated or insufficiently corrected bone deformities. Surgical navigation systems are being developed in an attempt to ease cam resection technique and make it more reproducible. In principle, those systems should allow more complete correction of the deformity even for less experienced surgeons. In addition, they should make the procedure safer, avoiding potential risks of excessive resection.

Labral Repair

Upon joint entry, a systematic examination should be performed of the entire acetabular labrum. The fibrocartilaginous labrum is normally adhered to the acetabular rim and transitions to the hyaline articular cartilage in a zone of approximately 1 to 2 mm. The labrum is widest anteriorly and thickest superiorly, corresponding to the weight-bearing region of the acetabulum (7). The labrum has been shown to provide approximately 5 mm of additional femoral head coverage and primarily function as a physiologic joint seal. A torn labrum is thought to alter load transmission in the joint and increase articular cartilage consolidation (5). In our practice, we observe five types of labral tears: detached, midsubstance longitudinal, flap, frayed, and degenerative. A labral tear can be a source of hip pain, but also can cause mechanical symptoms and contribute to hip instability. In the hip, labral tears have been related to joint degeneration. Patients undergoing labral repair had significantly less radiographic evidence of progression of osteoarthritis at 1 and 2 years compared with those who had their labrum resected (8).

Once the labral pathology has been characterized, correction is necessary. Most labral lesions are due to femoroacetabular impingement and these bony deformities need to be corrected to protect the repair. Tear size does not preclude arthroscopic fixation. Mechanical débridement of nonviable tissue is performed using a 4.5-mm full radius shaver. Often a previously unrecognized flap or area of gross delamination becomes more apparent. The quality of the tissue and the nature of the tear are evaluated at this point. Preserving as much of the viable acetabular labrum as possible is important to optimize joint congruence, evenly distribute force contact loads, and prevent further joint degeneration. Equally as important is recognizing an unstable construct for irreparable tissue. Generally, degenerative tears and tears that are of a frayed or flap nature in very thin labrums are not considered to be repairable. In that case, labral reconstruction might be a good option to improve stability in active patients.

Anchors are placed about 2 mm off the acetabular rim in the area of the rim trimming under direct visualization of the entry point and the adjacent articular surface (Fig. 51.6). In general, the anterolateral portal allows the insertion of anchors in the superolateral aspect of the acetabulum, where the most lesions are found. As the guide, a sleeve is directed to the trimmed acetabular margin in a divergent direction to avoid intra-articular penetration, a cranial angle of about 30° to 45° is often observed in the coronal plane. In general, the direction in the transverse plane for placement of anchors at 12-o’clock position (zone 3) in the acetabulum is parallel to the ground. As more anterior placements are necessary, a forward inclination of the guide is performed. The limits for that is usually the position corresponding to 2-o’clock position (considering the right acetabulum) where the insertion angle may be too acute. For the insertion of anterior-most (zone 1) anchors, the

midanterior lateral portal should be used. Fluoroscopy may be used during the procedure to ensure optimal placement.

midanterior lateral portal should be used. Fluoroscopy may be used during the procedure to ensure optimal placement.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree