CHAPTER 41 Advanced Techniques

PART A Arthroscopic Management of Lateral Epicondylitis

INTRODUCTION

Lateral epicondylitis, or tennis elbow, is the most common affliction of the elbow.

The origin of the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) has been implicated as the source of pathology in this condition.2,5,7–10,13–16,18 Reported histopathologic findings in the affected tendon origin include vascular proliferation and hyaline degeneration, which are consistent with a chronic, degenerative process.10,14,18,20 Most commonly, surgical treatment is directed at excision of this pathologic tissue through an open approach or more recently arthroscopic methods.1,3,5,6,11,15,17,19,21,22

This chapter covers the anatomy of the extensor tendon origins at the humeral epicondyle based on anatomic dissections.4 The location of the ECRB tendon origin is defined relative to intra-articular landmarks. Using these data, a technique for arthroscopic lateral epicondylitis surgery is presented with early clinical results.

ANATOMY

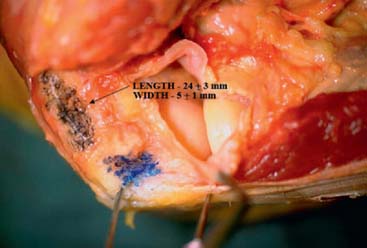

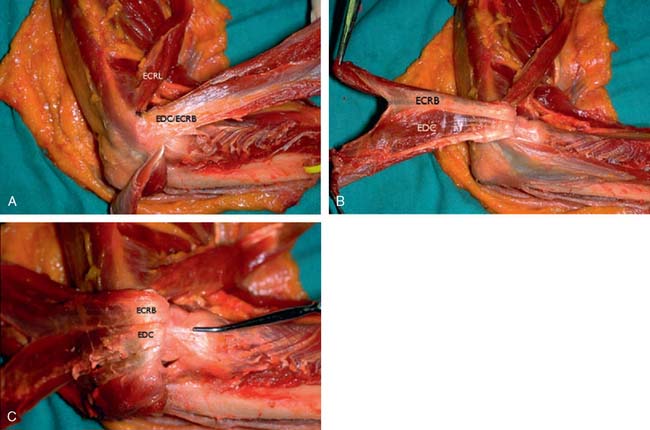

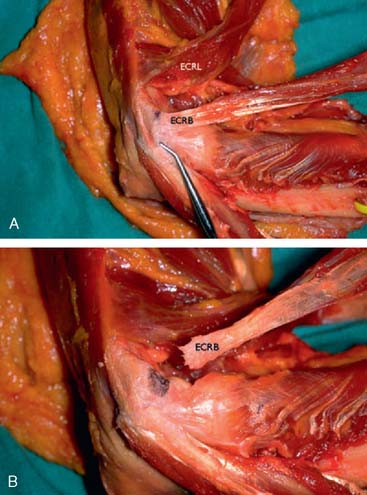

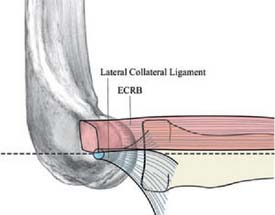

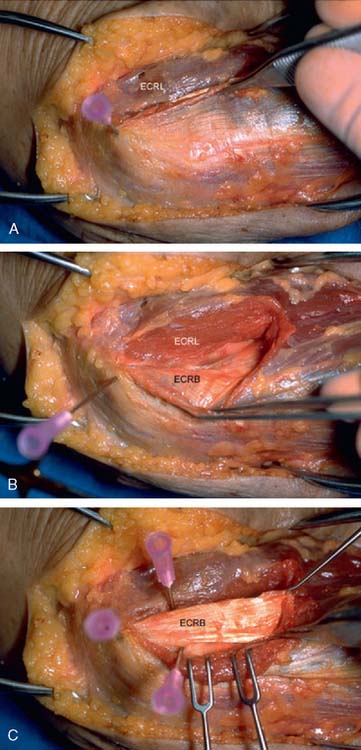

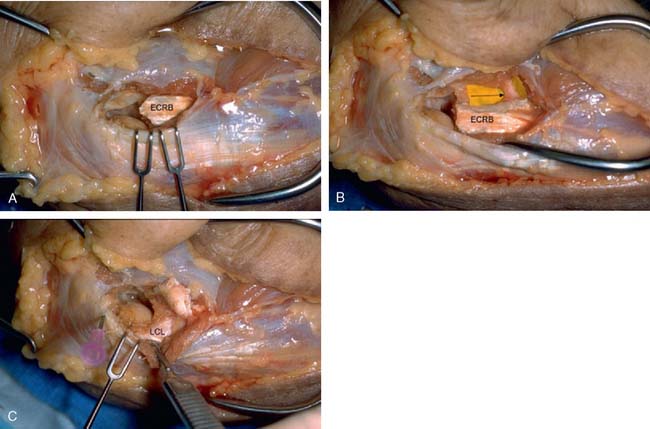

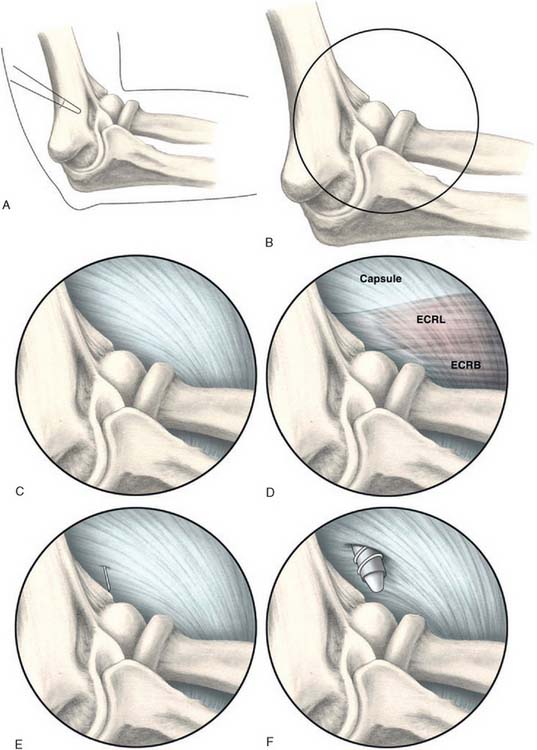

The origin of the ECRL is entirely muscular along the lateral supracondylar ridge of the humerus (Fig. 41-1). The muscle origin has a triangular configuration, with the apex pointing proximally. In contrast, the origin of the ECRB is entirely tendinous. Although it blends with the origin of the extensor digitorum communis (EDC), when dissected from a distal to proximal direction and using the tendon undersurface, it can be separated from the EDC back to the humerus (Fig. 41-2). The anatomic origin of the ECRB is located just beneath the distal most tip of the lateral supracondylar ridge (Fig. 41-3). The footprint is diamond shaped, measuring approximately 13 by 7 mm (Fig. 41-4). At the level of the radiocapitellar joint, the ECRB is intimate with the underlying anterior capsule of the elbow joint, but it is easily separable at this level.4

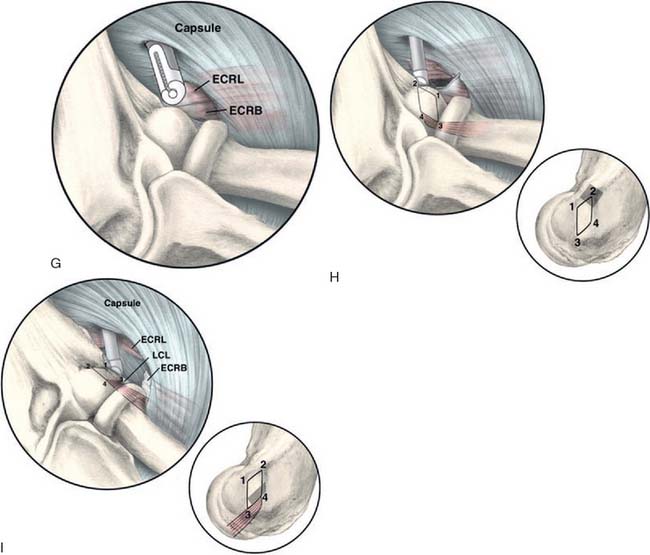

In an effort to develop a strategy for arthroscopic identification and release of the tendon origins, we performed a cadaveric study. The ECRB was identified at the level of the radiocapitellar joint by first separating the ECRL anteriorly from the extensor aponeurosis posteriorly (Fig. 41-5). The EDC origin was then dissected from anterior to posterior to expose the underlying ECRB tendon. The anterior and posterior borders of the ECRB were marked with intra-articular 18-gauge needles, and the ECRL/EDC interval and the skin were repaired (Fig. 41-5).

Dissection of the specimens revealed an intact extensor aponeurosis and a complete release of the underlying ECRB in all cases (Fig. 41-6). The capsule was identified as a separate layer beneath the ECRB release. The collateral ligament origin was not violated, and the PIN was well distal to the release and not compromised in any case (see Fig. 41-6). Using these data, an arthroscopic technique was designed for lateral epicondylar release.4

TECHNIQUE

Next, a standard anteromedial portal is established (Fig. 41-7). This is started several centimeters proximal and anterior to the medial epicondyle and well anterior to the palpable intermuscular septum. Care is taken to slide along the anterior humerus, and the joint is entered with a blunt introducer or a switching stick. This medial portal allows one to view the lateral joint including the radial head, capitellum, and the lateral capsule. It is often helpful at this point to open the inflow to allow distension of the capsule. If visualization is a problem, a retractor can be introduced through a proximal anterolateral portal 2 to 3 cm proximal and just anterior to the lateral supracondylar ridge. A simple freer elevator is useful for this purpose. By tensioning the capsule anteriorly, improved visualization of the lateral capsule and soft tissues can be achieved.

A modified anterolateral portal is established using an inside-out technique. This is started 2 to 3 cm above and anterior to the lateral epicondyle (see Fig. 41-7). The portal is slightly more proximal than a standard anterolateral portal. This allows instrumentation down to the tendon origin rather than entering the joint through the ECRB tendon itself. If lateral synovitis is present, this can be débrided with a resector.

The capsule is next released. Occasionally in epicondylitis, one can find a disruption of the underlying capsule from the humerus (Fig. 41-8). Most commonly, the capsule is intact although small linear tears can be present (Fig. 41-9). We have found it easier to release the lateral soft tissues in layers using a monopolar thermal device. In this way, the capsule is first incised or released from the humerus. When it retracts distally, one can appreciate the ECRB tendon posteriorly and the ECRL, which is principally muscular, more anterior. As noted earlier, the ECRB tendon spans from the top of the capitellum to the midline of the radiocapitellar joint.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree