Acute Ankle Conditions

Mark A. Hardy

Gina A. Hild

Ankle injuries occur in the United States at an incidence of 1 in 10,000 persons per day (1). The majority of these injuries occur in individuals between the ages of 10 and 19 years during sporting activity. Males have a higher incidence of sprains between the ages of 15 and 24 years, and females have a higher incidence over the age of 30 years. Basketball is responsible for approximately 41.1% of all athletically induced ankle injuries, followed by football at 9.3%, soccer at 7.9%, and running at 7.2% (2).

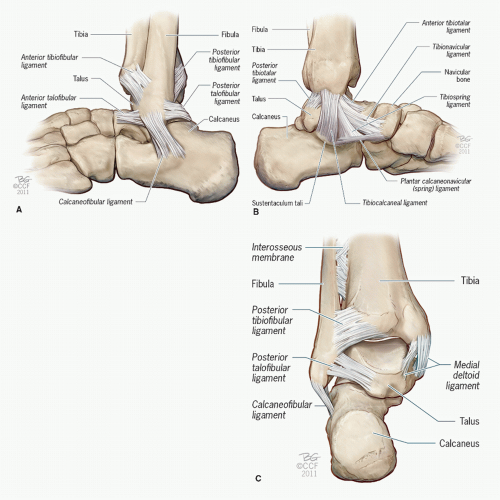

An ankle sprain is defined as an injury to lateral ligaments of the foot (1). Mechanism of injury for a lateral ankle sprain involves inversion and adduction on a plantarflexed foot (3), which results in tearing of the lateral ligaments, most commonly the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) (4,5 and 6). Calcaneofibular ligaments (CFLs) and posterior talofibular ligaments (PTFLs) can also be damaged via this mechanism. Eversion mechanisms result in deltoid ligament injury, and external rotation mechanisms can result in a syndesmosis sprain, otherwise referred to as the “high ankle sprain” (Fig. 50.1).

INDICATIONS AND GOALS

Ankle injuries can result in long-term swelling and pain. Functional instability and stiffness of the ankle can persist despite adequate treatment. Significant cartilaginous trauma can also lead to arthritic changes over time (6). Goals of treatment should be to minimize long-term swelling, restore stability to the lateral complex of the ankle, and restore full function of the ankle (1,7).

EVALUATION/PATHOMECHANICS/RATIONALE

RISK FACTORS

A number of risk factors exist for the development of lateral ankle injuries, including a cavovarus foot type, increased foot width, high longitudinal arch, laterally based gait pattern, and subtalar joint instability (8). Increased eversion-to-inversion strength ratio and increased strength in plantarflexion compared with dorsiflexion strength have also been implicated as potential risk factors for an acute ankle injury (9). It is the authors’ experience that individuals with metatarsus adductus or skew foot types may also have elevated risk.

CLASSIFICATION

Ankle sprains are graded according to severity. Grade I injury involves a mild stretching of the lateral ligament complex of the foot. No joint instability is noted. Grade II injury involves a ligament tear or partial rupture (usually of the ATFL) of the lateral ligament complex. Mild instability is noted. Grade III involves complete disruption of the lateral ligament complex, and instability of the ankle joint is seen (1).

EXAMINATION

Clinical

When completing an ankle exam after an acute injury, it is imperative that it is performed from proximal to distal in a systematic and reproducible fashion. All potentially injured areas should be evaluated for injury. Once practitioners become proficient with this examination, it can be completed within a couple of minutes.

Following adequate assessment of peripheral pedal pulses and neurologic sensation, the following 15-step ankle analysis should be performed on every patient:

Palpate proximal fibula to rule out a Maisonneuve fracture.

Evaluate syndesmosis with the external rotation and medialto-lateral squeeze tests.

Palpate medial malleolus.

Palpate deltoid and medial ligamentous complex.

Palpate along the course of the posterior tibial tendon.

Palpate lateral malleolus.

Palpate ATFL. Perform the anterior drawer test as described below.

Palpate CFL. Perform the talar tilt test as described below.

Palpate PTFL.

Palpate along the course of the peroneal tendon. Evaluate for concomitant subluxation.

Palpate anterior talus with the foot in a plantarflexed position. Ankle is brought through a full range of motion to rule out osteochondral defects.

Palpate Achilles tendon.

Palpate calcaneal wall and its anterior process.

Palpate dorsal navicular and tuberosity attachments.

Palpate fifth metatarsal base.

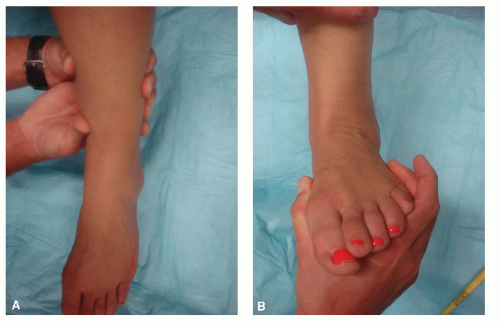

Evaluation of the integrity of the ATFL is achieved with an anterior drawer test. The examiner holds the lower leg locked from front to back and attempts to anteriorly translate the foot on the leg (Fig. 50.2). Although the test can be performed at any time, it is thought that the individual will have less guarding after 3 days from the initial injury. Accuracy is also improved if the test is performed under general anesthesia. The injured limb should be compared with the uninjured limb, and a difference of 4 mm or greater is considered to represent laxity within the ATFL (10). Less than 2 mm would be considered normal. Although this test is utilized to evaluate integrity of the ATFL, if the CFL is additionally injured, an increase in anterior translation will be seen (11).

Evaluation of the integrity of the CFL is achieved with a talar tilt test. The examiner holds the leg locked from side to side and inverts the heel. This is usually performed with the

assistance of an anteroposterior (AP) radiograph so that the angle between the tibia and talus can be measured. A comparison of the opposite limb should be performed. A difference of 5 to 15 degrees between limbs is considered significant for CFL disruption. Consideration should also be given to the fact that individuals may have a laxity within their CFL but may not have clinical symptoms of instability (Fig. 50.3).

assistance of an anteroposterior (AP) radiograph so that the angle between the tibia and talus can be measured. A comparison of the opposite limb should be performed. A difference of 5 to 15 degrees between limbs is considered significant for CFL disruption. Consideration should also be given to the fact that individuals may have a laxity within their CFL but may not have clinical symptoms of instability (Fig. 50.3).

Figure 50.1 A: Lateral ankle ligament complex. B: Medial ankle ligament complex. C: Posterior view ankle ligaments. (Copyright Cleveland Clinic Foundation © 2011.) |

When evaluating for syndesmotic injury, a number of clinical clues exist. Pain will usually be noted along the medial aspect of the ankle as well as along the length of the syndesmosis. Swelling will be seen proximal to the ankle joint in the early stages of injury (12). Two clinical tests can be performed to determine if the syndesmosis is injured. The “external rotation test” involves stabilizing the leg with one hand and externally rotating the foot on the leg with the other hand. If significant pain ensues, this is considered a positive finding. The “tibialfibular squeeze test” can also be performed. With this test, the tibia and fibula are compressed together about three centimeters proximal to the ankle joint. If pain ensues distally, this is also considered a positive test. Conflicting evidence exists in the literature as to which test is more accurate (Fig. 50.4).

Radiographic

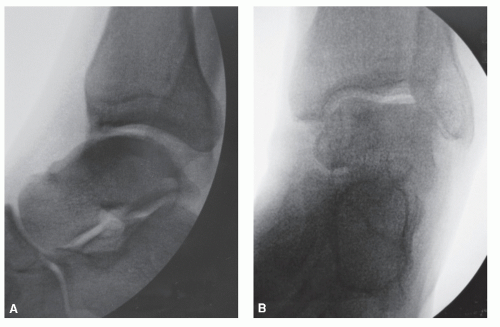

Stress radiographs include additional evaluation of the anterior drawer and talar tilt with radiographs. Anterior drawer is performed and evaluated with a lateral radiographic study, and talar tilt is performed and evaluated with an AP view. These

views allow the clinician to quantify an exact degree of instability. Testing should be performed on both the injured and uninjured side so an adequate comparison can be made (Fig. 50.5).

views allow the clinician to quantify an exact degree of instability. Testing should be performed on both the injured and uninjured side so an adequate comparison can be made (Fig. 50.5).

The Ottawa Ankle Rules were developed from a prospective Canadian study performed by Stiell and colleagues in 1992. They evaluated 750 individuals with blunt ankle trauma and determined significant variables that would predict the likelihood of fracture versus soft tissue injury. These results were 100% sensitive and 42% specific, and it was predicted that with the use of their rules, unnecessary radiographic imaging would be reduced by 36% (13).

Figure 50.3 Talar tilt clinical test is utilized to evaluate the integrity of the CFL. The examiner holds the leg locked from side to side and inverts the heel. |

Ottawa Ankle Rules:

Ankle radiographs are necessary if there is pain near the malleoli and one or more of the following: age over 55 years, unable to bear weight immediately, and in the

emergency department more than four steps, and bone tenderness to the posterior edge or tip of either malleolus.

Figure 50.5 A: Positive anterior drawer test performed under fluoroscopic examination. B: Positive talar tilt test performed under fluoroscopic examination.

Foot radiographs are necessary only if there is pain in the midfoot and there is bone tenderness to the navicular, cuboid, or base of the fifth metatarsal (13).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree