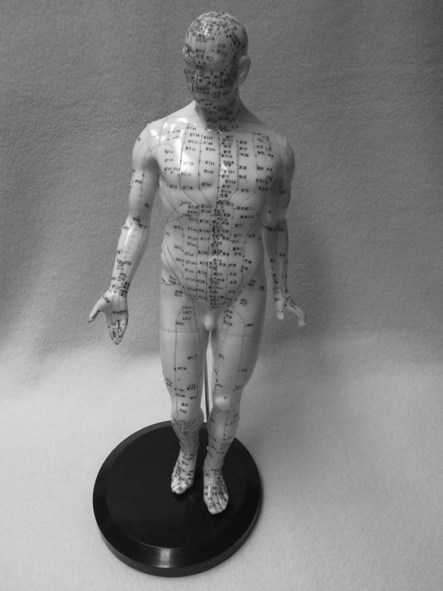

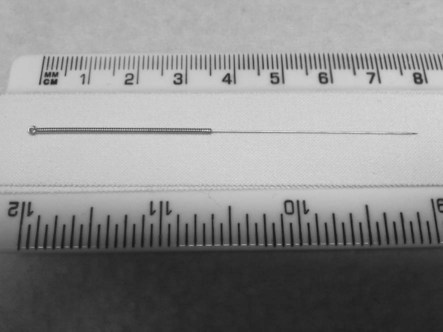

While it is widely assumed that acupuncture originated in China, some evidence of its existence in central Europe was discovered in 1991 when a frozen corpse, subsequently named Oetsi the iceman and estimated to be the remains of a 5000-year-old male, was found with tattoos largely consistent with acupuncture points (Dorfer et al. 1999). Furthermore, the location of these points appeared consistent with an acupuncture prescription for the treatment of the lower back and abdominal conditions which study of the remains would suggest this man suffered from (Moser et al. 1999). In China, the discovery of sharpened bones and stones (known in Chinese as bian or bian shi) dating to the Neolithic period, or 8000 years ago, has been suggested to be evidence of the practice of a form of acupuncture, but it is more likely that these sharpened tools were, at least initially, used for blood-letting and the drainage of abcesses (Ma 1992; Basser 1999; Unschuld 1985). It is thought that acupuncture practice may well have had origins in the once near-universal practice of medical blood-letting which began in Ancient Greece and was used to remove what was diagnosed as stagnant blood, a description sometimes used in traditional Chinese medicine to describe the state of qi flow in ill health which may be beneficially affected by needling. Regardless of its specific origins, the classic text Huang Di Neijing (translated as Inner Classic of Huang Di) introduced the practical and theoretical foundations of what subsequently became known as acupuncture (Ramey and Buell 2004). Commonly referred to as The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine, this text is judged to be approximately 2000 years old and is presented as a series of questions and answers between the then Emperor, Huang Di and his physician Chi-Po (Ma 1992; Kaptchuk 2002; White and Ernst 2004; Baldry 2005). Over the centuries acupuncture developed and was used alongside herbal medicine, diet, massage and the use of heat therapies, including the burning of moxa or moxibustion in China (Ma 1992). A sixteenth century acupuncture specialist cast bronze figurines to assist in the location of acupuncture points (Ma 1992). It was not until 1601 that the publication of The Great Compendium of Acupuncture and Moxibustion by Yang Ji-Zhou formulated what we now recognise as acupuncture practice detailing 361 points (Kaplan 1997). Throughout the early development of acupuncture it is important to note that traditional Chinese medicine approaches and treatment philosophies were based upon subjective perceptions and in the absence of medical dissection or surgical exploration (Basser 1999; Unschuld 1985; White and Ernst 2004). The practice of acupuncture was adopted by Japan and Korea in the sixth century and by Vietnam between the eighth and tenth centuries (Baldry 2005). France led the way in Europe, adopting the practice of acupuncture after Jesuit missionaries returned with reports of its practice in the sixteenth century. In 1683, the first medical treatise to appear in the West on ‘acupuncture’ (a term coined by its author from the Latin acus = needle and pungere = to prick) was written by the physician Willem Ten Rhijne (Bivins 2000; Baldry 2005). Throughout the eighteenth century, in both Europe and America, doctors practised acupuncture, formulating a Western rationale based on the scientific discoveries of their day (Kaptchuk 2000). Ironically, this was at a time when acupuncture use was falling out of favour in China (Baldry 2005). By the mid-nineteenth century acupuncture had become unfashionable and politically incorrect in the west, and in China its use was restricted to rural areas following a decree by the Daoguang Emperor citing it as an impediment to medical advancement (Ernst and White 1999). This decree effectively meant that acupuncture was no longer officially recognised by The Imperial Medical Institute and was, along with other forms of traditional Chinese medicine, banned in 1929 in favour of modern scientific medicine (Ma 1992). In 1949 with Chairman Mao Tse-Tung as head of the communist revolution and the establishment of The People’s Republic of China, acupuncture, along with other forms of traditional Chinese medicine experienced a revival. This resurgence in traditional Chinese medicine was largely for political reasons and linked to the Cultural Revolution in China (Unschuld 1985). In fact, it was at this time that the existing divergent forms of therapeutic intervention in China were consolidated into what we now refer to as traditional Chinese medicine (Birch and Kaptchuk 1999). Alongside this, research into acupuncture was promoted in China which later led to Han’s work into the effects acupuncture may have on neurotransmitter release (Han and Terenius 1982). Owing to China’s political isolation this renewed enthusiasm for traditional Chinese medicine went unnoticed by the West until the early 1970s. In preparation for Richard Nixon’s 1972 visit, Henry Kissinger visited China in 1971. Among his press entourage was a man who was surgically treated for acute appendicitis while in China and received postoperative acupuncture for abdominal pains (Reston 1971). His report of this care in the New York Times was the catalyst for a rush of interest by US physicians in seeing the surgical benefits of Chinese acupuncture first hand (Diamond 1971). Perhaps the most enduring and controversial of these first-hand experiences was when Dr Isadore Rosenfeld observed open heart surgery in a young female patient ostensibly using acupuncture points in her ear (auricular acupuncture) with electrical stimulation (electro-acupuncture) in place of standard anaesthetics. It now seems clear that what Dr Rosenfeld observed was, at best, an exaggeration of the analgesic affects of auricular electro-acupuncture and, at worst, and more likely, an elaborate hoax with much of the analgesic effect being attributable to low doses of midazolam, droperidol and fentanyl. Nonetheless, this and the experiences of other visiting physicians, galvanised interest in acupuncture analgesia among the medical community at the time. Unfortunately, reports of these experiences were presented more as sensationalist journalistic pieces than objective academic works and much of the hype regarding the potential benefits of acupuncture this created was not well founded. Indeed, a recent systematic review by Lee and Ernst (2005) concluded that the evidence for acupuncture analgesia in surgery was inconclusive. Acupuncture is an intervention involving the insertion and manipulation of fine needles into the body to achieve a therapeutic effect. From a traditional Chinese medicine perspective the anatomical sites at which these needles are inserted are specified and these points are located along channels (mai in Chinese) that have come to be known as meridians in the West (in part owing to their similarity to geographical meridian lines). It is worth noting that ancient texts demonstrate that these meridians were developed from clinical experience with moxibustion and not acupuncture (Harper 1998). There are 12 principle meridians with both superficial and deep representations, and a number of so-called extraordinary meridians. Again, from a traditional Chinese medicine perspective, these meridians are believed to have specific effects on the physiology of body organ systems and are named accordingly, for example Lung (LU), Heart (HT), Pericardium (PC), Stomach (ST), Large Intestine (LI), Small Intestine (SI) and Bladder (BL) meridians (Figures 18.1 and 18.2). The insertion of acupuncture needles and their stimulation either manually or via electrical stimulation is believed to effect the flow of qi, pronounced ‘chi’, and commonly translated as vital energy, life force or spirit, while a literal translation of the Chinese character for qi is ‘vapors rising from food’ (Basser 1999). It is believed in traditional Chinese medicine that by effecting qi flow along the meridians a person’s overall health and well-being can be beneficially influenced. In order to effectively produce this therapeutic effect it is commonly believed that needling stimulation is required to produce a specific sensation know in Chinese as de qi and described as a deep heavy aching sensation which may propagate along the needled meridian. Diagnosis in traditional Chinese medicine conceptually views the health status of an individual as a microcosm of nature and thus could be viewed as a human meteorological report (Kaptchuk 2002). Linked to this are the concepts of five fundamental universal elements and that of balancing a person’s yin and yang with those of nature, terms originally denoting the shaded and sunny aspect of a hill respectively. These terms of yin and yang are also used to classify acupuncture meridians, the former being on the inner aspect of a limb and the latter on the outer aspect. The individual acupuncture points are named and numbered according to the meridian along which they are located, for example LI4, ST36. Points are located on an individual’s body in relation to tendons, muscles and bony points, and a system of proportional measurements using the ‘cun’ as its base measurement which is the width of that individual’s interphalangeal joint of the thumb (Cheng 1987). Palpation is also viewed as being of great importance in locating points to needle. Historically, and in keeping with the traditional Chinese medicine view of health being related to a numerical and holistic paradigm, 365 points were described to reflect the days of the year without any further objective basis (Lun 1975). In addition to the overall effects which needling these points can have on an individual’s health and organ function, in traditional Chinese medicine specific acupuncture points are anecdotally believed to have specific effects on certain conditions, for example PC6 for nausea and vomiting, GB37 for conditions related to vision and BL60 for lower back pain (Maciocia 2005). These points are commonly referred to as ‘empirical’ points. In addition to these classical meridian points, needle insertion can be directed locally to the symptomatic area or into points of maximal tenderness referred to as ah-shi (translated as ‘oh yes’/‘that’s it’) points. Interestingly, the Chinese character used to denote an acupuncture point can also mean ‘hole’ suggesting that acupuncture points may be viewed as points of access to structures deeper in the body (Langevin and Yandow 2002). In 2000, the British Medical Association recommended the integration of acupuncture into practice (Silvert 2000). On the face of it, Western medical acupuncture may appear very similar to traditional Chinese medicine acupuncture. Needles are inserted often both local to the symptomatic region of the body and more distally along the arm or leg, often with points in the hand or foot. Once the needles are in place they are typically manipulated by hand or by electrical stimulation over the course of a treatment lasting anywhere from 5–30 minutes. The points are typically named using traditional Chinese medicine terminology and often empirical points are added to the points used. The key differences between Western and traditional Chinese medicine acupuncture is in the patient assessment, expectation and in the intention behind the treatment itself. While a traditional Chinese medicine approach would typically assess a patient’s ‘qi balance and flow’ by taking a history and using observation of the tongue, eyes and specific palpation of the pulse, a Western approach would seek to make a clinical diagnosis based on pathology using history and clinical assessment findings. In terms of the treatment itself, a traditional Chinese medicine practitioner would seek to alter qi movement and flow by needling, whereas a Western practitioner would attempt to stimulate specific neurochemical and both connective and contractile tissue responses by needling. In addition, a traditional Chinese medicine practitioner would chose points according to meridians with a consideration of the effects this may have on organ system physiology. Although Western acupuncture may still use classic traditional Chinese medicine nomenclature to specify the points used often no consideration is given to the potential effects on organ systems, for instance in the case of using points along the bladder meridian to treat lower back pain. Instead, the local, segmental, extra-segmental and central neurological effects are what concern a Western acupuncture practitioner. Acupuncture use by general practitioners (GPs) in the UK is increasing and it is now likely to be the most prevalent of all complementary therapies. Thomas et al. (2001) reported that in 1998 approximately 7% of English adults had received acupuncture treatment at some point. Within National Health Service (NHS) chronic pain clinics, acupuncture is estimated to be offered in 84% of cases (Woollam and Jackson 1998). According to the Acupuncture Association of Chartered Physiotherapists (AACP) there are approximately 5000 AACP-registered physiotherapists now working in the NHS and in private practice in the UK. As with any physiologically active and invasive therapeutic intervention, considerations of not only the effectiveness but also of the safety of acupuncture are necessary. The mere fact that acupuncture has been practised for centuries does not provide sufficient evidence of its safety. Historically, autoclave procedures were employed for sterilising needles and it was not until reports of acupuncture-related cross infection, such as hepatitis B (Kent et al. 1988) coupled in no small way with the outbreak of AIDS in the 1980s, that single-use needles were advocated. It is clear that reports of adverse events and more serious complications attributed to acupuncture during the 1970s and 1980s highlight the improvements in acupuncture safety that have been made in the past three decades. Further reports of acupuncture-associated hepatitis B transmission were, however, reported in the 1990s (Rosted 1997; White 1999). The latter of these reports not only recommended the use of single-use, disposable needles, but also the vaccination of all acupuncture practitioners against hepatitis B. During the 1990s it was proposed that a theoretical risk of transmitting variant Creutzfeldt-Jacob Disease existed even with autoclaved needles, further supporting the use of sterile single-use needles. The other potential complication in the thoracic region is injury to the lungs or pleura through needling. Needling in the parasternal region or along the midclavicular line to a depth of 10–20 mm has been shown to be sufficient to reach the lungs in cadaveric study. Numerous cases of pneumothorax induced by acupuncture have been reported (White 2004). Points which have resulted in injury to these structures include Stomach 11 and 12 (ST11, ST12). Caution should be exercised when needling Stomach 13 (ST13), Lung 2 (LU2) and Kidney 27 (KID27). Kidney (KID22–KID27), Stomach (ST12–ST18) and Bladder (BL41–BL54) points should all be needled bearing in mind the depth of the lung at these sites. As far as the abdominal viscera are concerned, few reports of complications have been published apart from rare lesions of the intestine and bladder, plus a report of a foreign body in a kidney identified as an acupuncture needle. Four reports of blood vessel injury are briefly detailed by Peuker et al. (1999). These involved a partially thrombosed pseudoaneurysm adjacent to the costocervical artery (Fujiwara et al. 1994), a false aneurysm of the popliteal artery following deep needling of Bladder 40 (BL40) (Lord and Schwartz 1996), a deep vein thrombophlebitis in the upper calf (Blanchard 1991) and anterior compartment syndrome in the upper calf in a patient on anticoagulant therapy (Smith et al. 1986). A series of articles by Peuker and Cummings (2003a, 2003b, 2003c) expanded upon this work of examining anatomy as it pertains to acupuncture. These three articles divided the body into three sections: the head and neck, the chest, back and abdomen, and the upper and lower limbs, and detailed the pertinent neuromusculoskeletal anatomy to guide acupuncturists in targeting the intended target and avoiding neurovascular targets. A review by Ernst and Sherman (2003) concluded that in almost all cases poor practice and lack of adherence to recommended hygiene procedures was responsible for serious adverse reactions to acupuncture. This fact obviously supports the continued regulation of acupuncture practitioners by organisations such as the British Medical Acupuncture Society (BMAS) and the AACP in the UK. Throughout the 1970s much of the medical and scientific community attributed the benefits of acupuncture to the placebo effect. However, this belief failed to account for the benefits of acupuncture in young children and in animals. In order to satisfy standards of Western scientific rigor and understandable scepticism regarding acupuncture and its effects, clinical research was required. Western evidence-based medical research into acupuncture has since largely dismissed traditional Chinese medicine concepts of qi and meridians. In their place neurochemical and anatomical models have been proposed based on the best evidence from research studies. At the extreme this Western scientific approach is typified by Felix Man’s assertion in the 1970s that ‘Acupuncture points and meridians in the traditional sense, do not exist’ (Mann 2004). Principally, this research investigated the analgesic effects of acupuncture. Initially, the best theory to explain acupuncture analgesia was the gate control theory of pain proposed by Melzack and Wall in the 1960s (Melzack and Wall 1965). The fundamental basis of this model was that a counter stimulus could effectively supersede the noxious stimulus at the spinal cord level thus suppressing the nociceptive pathway. During the late 1970s extensive research was performed by Bruce Pomeranz, alone and with others. Pomeranz used research evidence to outline a sequence of neurochemical events following the insertion of an acupuncture needle. At spinal cord level the acupuncture stimulus was believed to stimulate the release of dynorphin and encephalin leading to the attenuation of noxious transmission. At mid-brain level a further release of encephalin affected a descending inhibitory pathway back to the spinal cord. Finally, Pomeranz proposed that at the level of the hypothalamus the stimulation of release of beta-endorphin into the mid-brain by the arcuate nucleus and pituitary re-enforced this descending inhibition (Pomeranz and Chui 1976; Pomeranz et al. 1977; Pomeranz 1978). Subsequent research focussed on the potential effects acupuncture may have on the release of opioids, such as endorphin. One of the most significant and seminal of these pieces of research was carried out in Beijing and looked into the neurochemistry of acupuncture analgesia (Han and Terenius 1982). This study found that acupuncture could affect the release of neurotransmitters, especially opioid peptides, which could explain its analgesic effects. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s frequent but ultimately inconclusive attempts were also made to find anatomical correlates for acupuncture points. These studies pointed to the endings of a variety of sensory nerves (Ciczek et al. 1985), areas of dense neuro-vascularity (Bossy 1984) and motor end-plates (Liu et al. 1975; Gunn et al. 1976; Dung 1984) as potential anatomical target sites for needling. Another line of research looked at the physiology of acupuncture points. On many occasions skin conductance has been evidenced to be higher at acupuncture points when compared with adjacent skin (Reichmanis et al. 1976; Comunetti et al. 1995). Unfortunately, inadequate statistical testing, control and subject numbers have adversely affected the quality of these studies. With the advent of positron emission tomography (PET) scanning and, in particular, functional magnetic resonance imagery (fMRI) in the 1990s, there was a new method of investigating the cortical effects of needling in acupuncture. For instance, it was possible to study the effects of needling on activity in areas of the brain believed to be associated with the processing and perception of pain. While such research took many forms and investigated acupuncture from a variety of different perspectives, perhaps the most talked about study was published in 1998 and sought to correlate brain activity with an empirical point associated with visual disorders (Cho et al. 1998). This study focussed on an acupuncture point located on the lateral aspect of the foot referred to as Bladder 67 (BL67) which, according to traditional Chinese medicine theory, is an empirical point used in the treatment of eye disorders (Kaptchuk 2000; Stux et al. 2003). The authors observed fMRI activity in the brain stimulated by needling BL67 and fMRI activity stimulated by visual light stimulation. A correlation was found between the specific areas of cortical activation leading the authors to claim that this supported traditional Chinese medicine theory regarding this empirical point. However, a retraction was published in 2006 by the authors of the original article aside from three: J.P. Jones, J.B. Park and H.J. Park. The other five authors stated that they ‘no longer agree with the results’ of the original article and conclude from research carried out in the intervening years that there is no research evidence to support point specificity in acupuncture. By the turn of the century, research had revealed evidence that acupuncture had a role in the regulation of a variety of physiological functions, protection against infection and as an analgesic (WHO 1999). More specific study revealed that needle manipulation at the point known as Large Intestine 4, or LI4, could modulate activity as seen on fMRI in the limbic system of the brain and in subcortical regions (Hui et al. 2000). This finding could go some way towards explaining some of the anecdotally reported multisystem clinical effects of acupuncture treatment. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) review of acupuncture evidence in 1999, which limited its scope to randomised controlled and controlled clinical trials with adequate subject numbers, advocated the use of acupuncture for pain relief, especially in chronic cases. This is because for chronic pain states, acupuncture has been shown to be equally effective as morphine but without the potential side effects. Of note is the similarity between conditions where acupuncture is advocated and those where an element of central sensitisation is suggested, such as osteoarthritis, some forms of headaches, fibromyalgia and musculoskeletal disorders with generalised pain and hypersensitivity, such as chronic lower back pain. Acupuncture use is supported in the WHO report for the management of headaches and a variety of musculoskeletal conditions such as neck pain or cervical spondylitis (David et al. 1998), fibromyalgia (Deluze et al. 1992), common extensor tendinopathy of the elbow (Haker and Lundeberg 1990; Molsberger and Hille 1994), knee osteoarthritis (Berman et al. 1999) and chronic lower back pain (Lehmann et al. 1986). In the case of rheumatoid arthritis the WHO report cites evidence supporting the benefits of acupuncture treatment to address the pain, inflammation and immune system components of this auto-immune condition (WHO 1999). Furthermore, and in summary, the report presents some convincing evidence supporting the use of acupuncture in the treatment of traumatic and postoperative pain (Jiao 1991), as an adjunct in stroke rehabilitation (Johansson et al. 1993) in reducing exercise-induced asthma (Fung et al. 1986), as an anti-emetic (Vickers, 1996), and in some gynaecological and obstetric conditions (Helms 1987; Chen 1997).

Acupuncture in physiotherapy

A brief history of acupuncture

Acupuncture in the twentieth century

Acupuncture from A traditional chinese medicine perspective

Western medical acupuncture

Prevalence of acupuncture use

Safety of acupuncture

Acupuncture research in the twentieth century

Brain imaging acupuncture research

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine