Chapter 7 Achilles Tendon Disorders Including Tendinosis and Tears

Introduction

The Achilles tendon is formed by a coalescence of fibers from the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles. This complex spans both the knee and ankle joints, making it more susceptible to injury than muscles that span a single joint. The Achilles tendon is notably susceptible to injury with concomitant knee extension and ankle dorsiflexion. The medial and lateral heads of the gastrocnemius originate from the medial and lateral femoral condyles, respectively. The soleus muscle originates from the posterior proximal tibia and fibula. More distally, the medial and lateral gastrocnemius and soleus tendons coalesce to form the triceps surae complex. The Achilles tendon then rotates 90 degrees such that the medial gastrocnemius position is more posterior and superficial. This rotation may result in torque stresses that can increase the risk of tendinitis.1After passing distal to the posterior superior calcaneal tuberosity, the Achilles tendon inserts into the posterior and plantar calcaneal tuberosity about halfway between the dorsal and plantar aspects of the calcaneus.

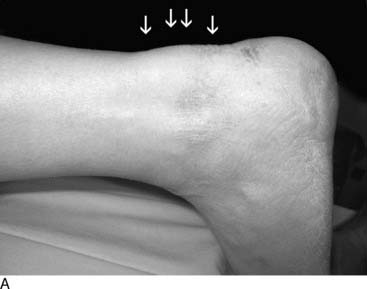

The retrocalcaneal bursa lies between the distal Achilles tendon and the posterior superior calcaneal tuberosity. It is horseshoe shaped and sits around the insertion of the Achilles, which has more fibers centrally and proximally. Anteriorly it is composed of fibrocartilage, whereas posteriorly it blends with the paratenon and commonly connects to the posterior Achilles tendon. The pre-Achilles bursa lies superficial to the Achilles between the Achilles and the skin. These bursae, composed of synovium, provide lubrication to assist with tendon gliding and to minimize tendon irritation. A large, sometimes abnormal prominence of the posterior superior calcaneus, Haglund’s deformity,2 may create repetitive frictional irritation on the Achilles tendon that can lead to tendinitis (Fig. 7-1, A and B).

The Achilles tendon is the strongest and longest tendon in the body, measuring approximately 12 to 15 cm in length. Although it is the main plantarflexor of the ankle, it also functions to invert the heel during late stance phase and thereby locks the transverse tarsal joint for push-off along with the posterior tibial tendon. It is subject to forces up to 10 times body weight during running, experiencing up to 7000 N of force.1,3,4

The blood supply to the Achilles tendon is segmental and is predominantly derived from anterior branches of the paratenon. Additional sources include intratendinous vessels, the posterior tibial artery, and distal osseous and periosteal branches. A relative zone of hypovascularity exists within 2 to 6 cm proximal to the calcaneal insertion, corresponding to the site of most Achilles tendon ruptures and noninsertional tendinitis.5,6

Achilles Tendinitis

Achilles tendinitis is common among athletes, affecting nearly 18% of runners.7–9 Repetitive impact-loading activities (overuse) such as jumping are responsible for the majority of cases.1 Other predisposing factors include poor extremity biomechanics (foot pronation, cavus foot, genu varum), improper training techniques (excessive running, sudden increase in intensity, uphill running), and poor shoewear.8 Another potential risk factor includes the previous use of fluoroquinolone antibiotics. Athletes commonly affected by tendinitis are involved in running, dancing, tennis, racquetball, basketball, and soccer (unnumbered box 7-1).

Puddu et al.10 classified Achilles tendinitis into three categories. Peritendinitis is characterized by inflammation affecting only the paratenon. Peritendinitis with tendinosis refers to inflammation involving both the paratenon and Achilles tendon. Tendinosis reflects isolated Achilles degeneration. Clain and Baxter1 later created an anatomic classification, separating tendinitis into insertional disorders, affecting the area of the enthesis, and noninsertional disorders, commonly affecting the tendon 2 to 6 cm proximal to the calcaneus.

Whereas noninsertional tendinitis occurs more often in younger, more active athletes, insertional Achilles tendinitis develops more often in those athletes who are older, less active, and sometimes overweight. Additionally, the presentation of bilateral insertional tendinitis typically occurs in young athletic men and is commonly associated with inflammatory disorders, including seronegative spondyloarthopathies.11,12

Noninsertional tendinitis

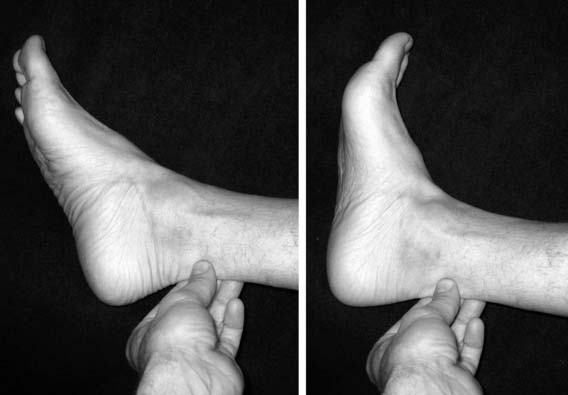

Peritendinitis is inflammation affecting only the paratenon. The Achilles tendon itself is uninvolved. In chronic cases, adhesions may form between the paratenon and tendon, leading to more profound pain and tenderness. Pain is noted most often at the initiation of activity (start-up pain) and improves with continued exercise. Acute pain typically resolves with rest. In chronic cases, however, the pain may persist and significantly impair further athletic participation. On examination, a localized, increased diameter that more commonly affects the medial side is appreciated with palpation of the tendon. Tenderness, and at times crepitus, is noted throughout all ankle range of motion (Fig. 7-2). Radiographs generally are unremarkable.

Peritendinitis with tendinosis represents further inflammation with associated intratendinous degeneration. Pain is more marked and constant. The tendon is thickened and infrequently has palpable intrasubstance calcifications (Fig. 7-3). The painful arc sign may help to distinguish between tenderness associated with peritendinitis and that associated with tendinosis. Tenderness related to peritendinitis will be constant in location as the ankle is brought through a range of motion, whereas tenderness associated with tendinosis will change position with ankle motion.13

Isolated tendinosis, or noninflammatory atrophic degeneration, is associated with normal aging and typically is accelerated by overuse. Most affected are middle-aged, recreational athletes. With repetitive trauma, microtears develop within the tendon, mostly in the hypovascular zone, leading to further fibrosis and degeneration.14 These athletes complain of weakness in push-off, with pain localized to the area approximately 2 to 5 cm proximal to calcaneus. Whereas ankle dorsiflexion commonly is limited, tendon elongation may develop with an associated increase in passive ankle dorsiflexion. Pathologic examination reveals fatty degeneration with disorganized collagen. Calcific deposits may be present (unnumbered box 7-2).

Insertional achilles tendinitis

Insertional tendinitis is an inflammatory reaction within the Achilles tendon affecting the enthesis, or tendon insertion onto the calcaneus. This disorder more commonly affects older, heavier, and less active athletes but can be seen in competitive athletes as well.12 An abnormally enlarged, bony prominence may aggravate this condition. There is a high association with Haglund’s deformity and retrocalcaneal bursitis, but unlike these disorders, insertional tendinitis involves the tendon itself. This most often results from chronic overuse and poor training habits. Improper techniques include inadequate stretching, rapid increase in training, running on harder surfaces, and heel running. Although pain initially follows exercise, particularly uphill running, symptoms may become continuous over time.

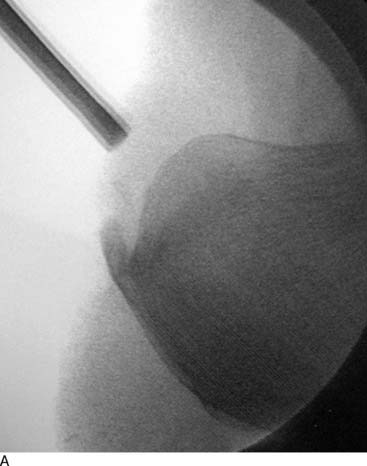

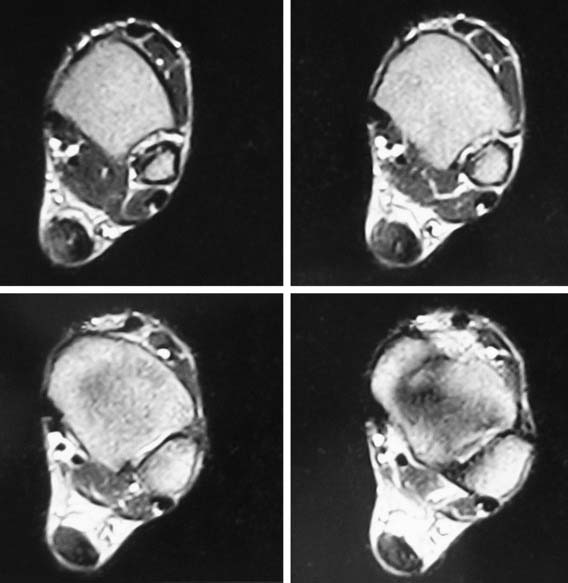

Pain, swelling, and warmth are noted specifically at the tendon-bone junction, the enthesis. In athletes, there often is a localized area of pain with a small spur. Ankle range of motion is painful, with dorsiflexion typically limited because of a tight Achilles tendon. External irritation from a shoe’s heel counter plays less of a role in provoking symptoms in athletes with Achilles tendinitis than in retrocalcaneal bursitis and Haglund’s deformity. Radiographs generally reveal calcifications or a bony spur at the most distal aspect of the Achilles insertion (Fig. 7-4, A). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) will show degeneration where the tendon attaches to the calcaneus (Fig. 7-4, B).

Haglund’s deformity

Haglund is credited with first describing the presence of a prominent posterolateral superior calcaneal tuberosity in 1927.2 This enlarged superolateral tuberosity predisposes the precalcaneal bursa to be compressed between it and any tightly fitting shoe heel counter, possibly leading to skin irritation and inflammation. Because of the association of shoewear, this disorder also has been referred to as a “pump bump” and “winter heel.” Although there is a frequent association with retrocalcaneal bursitis and insertional Achilles tendinitis, Haglund’s deformity generally does not involve the Achilles tendon.

Poorly fitting shoes generally are responsible for the development of symptoms of Haglund’s disorder. Other predisposing risk factors include the presence of a cavus foot and hindfoot varus. In rare cases, childhood apophyseal trauma may be a cause. In the nonathletic population, repetitive injury or trauma may result in bone overgrowth. Most affected are young women who wear fashionable high-heeled shoes. In the athletic population, we have observed this condition more commonly in males who participate in running sports. Long-distance runners are susceptible to this condition, as well as to the other Achilles tendon disorders (see Figs. 7-1 and 7-5).

Retrocalcaneal bursitis

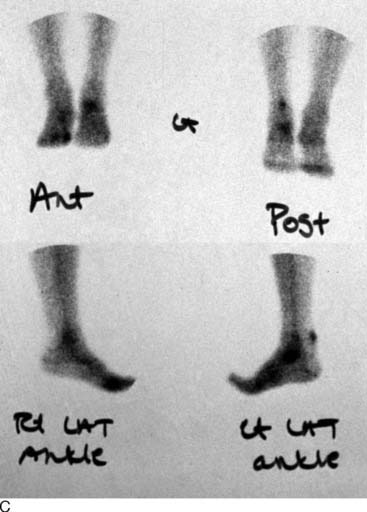

Athletes typically complain of pain with activities that force the ankle into dorsiflexion, particularly uphill running, and thereby compress the inflamed bursa between the posterosuperior calcaneus and the Achilles tendon. Schepsis et al.14 described the two-finger squeeze test, in which pain is noted when two fingers compress medially and laterally immediately superior and anterior to Achilles insertion. This area will be warm with a notable soft-tissue bulge. Pain is elicited with passive dorsiflexion. Radiographs often are not useful but may demonstrate loss of the retrocalcaneal soft-tissue shadow, as well as the presence of a posterosuperior bony prominence. MRI demonstrates soft-tissue changes anterior to the Achilles tendon above its insertion in the retrocalcaneal region (Fig. 7-6).

Treatment of Achilles Tendinitis

Nonsurgical treatment

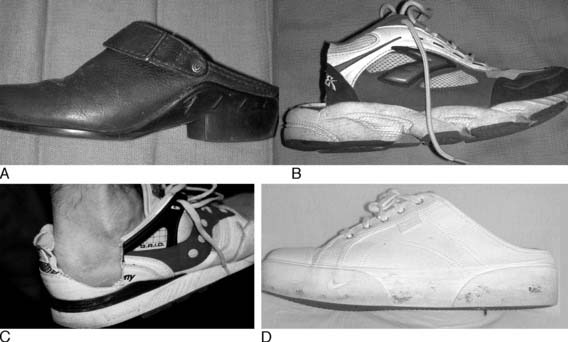

Initial treatment should include anti-inflammatory medications and a supervised program of Achilles stretching. At times, a heel lift (one-fourth to three-eighths inch), night splint, or temporary immobilization in slight plantarflexion with a removable walking boot or cast may be required. Relative rest with limitations on intensity, duration, or frequency of training and concomitant institution of nonstressful cross training (exercise bike, pool running, elliptical trainer) also should be helpful. If the athlete has notable foot pronation, a semirigid orthotic may improve overall foot biomechanics by supporting the medial arch. An open-back shoe may benefit those with Haglund’s or retrocalcaneal bursitis (Fig. 7-7). Additionally, deepening the heel counter or use of a heel pad or sleeve may be considered.

Intratendinous corticosteroid injections should be avoided because local use of these injections has been associated with tendon attrition and potential rupture. Although there is no strong evidence of similar deleterious effects after peritendinous corticosteroid injections, there are similar worries with an injection in the bursa. It would be advisable to immobilize the ankle temporarily after a retrocalcaneal injection because the retrocalcaneal bursa has a direct communication to the Achilles and may injure the Achilles tendon.12,15–17 In general, we advise against corticosteroid injections and use them only in very limited and specific circumstances.

For refractory peritendinitis, we have found that brisement may provide symptomatic relief in a third to half of total cases.18 Brisement consists of injecting 5 to 10 ml of sterile saline or local anesthetic agents into the Achilles tendon sheath; this may forcibly disrupt any adhesions between the paratenon and Achilles tendon. Repeating the injections two to three times over several weeks may be necessary to achieve success.14,18

Reported results of nonoperative treatment of insertional and noninsertional Achilles tendinitis have been generally successful. Studies have found that 70% to 90% of patients have found symptomatic improvement after corrections in their shoewear, training habits, and mechanics.8,18–22 There are, however, fewer predictable results with nonsurgical management in those with chronic tendinopathy and in the older athlete, as a result of greater degenerative tendon involvement.21

Surgical treatment

Noninsertional tendinitis

For noninsertional tendinitis, the choice of procedure is based on whether the disease involves the paratenon, tendon, or both. In peritendinitis, all adhesions are excised, and the surgeon also performs a limited resection of any thickened paratenon. The extremity is immobilized for 3 to 5 days, followed by a range of motion program to limit the recurrence of scar formation (Fig. 7-8).

When there is tendinitis and peritendinitis, elliptical excision of the tendon and longitudinal paratenon release is performed. Maffulli et al.23 have reported a success rate of approximately 70% after percutaneous longitudinal tenotomy of the middle third of the Achilles tendon. In this technique a no. 11 or no. 15 blade is introduced posteriorly through the skin and tendon. With the blade held stationary, the ankle is dorsiflexed and the tendon is cut longitudinally. Next the blade direction is reversed 180 degrees and the ankle is plantarflexed. The process is repeated through four additional incisions in the zone of the degenerative tendon (Fig. 7-9).

Tendinosis

The type of procedure chosen for treatment of tendinosis depends on many factors, the largest, in our experience, being the extent of tendon involvement, determined by clinical findings, ultrasound, or MRI. When less than 50% of the tendon is involved, we longitudinally ellipse the diseased tendon; and when more than 80% of the tendon is involved, a debridement and tendon augmentation (e.g., turndown) or transfer is recommended (Fig. 7-10). When there is between 50% and 80% involvement, the decision is determined by the patient, the sport, and the surgeon’s preference.

Typically a medial incision is made just anterior and parallel to the border of the tendon that is thickened, and the paratenon is entered. On the basis of maximal tenderness, MRI, or ultrasound localization of the degenerative zone of the tendon, an elliptical longitudinal excision of the diseased tendon is performed, leaving intact the anterior and posterior surfaces of the tendon. Essentially the zone of ellipsed tissue should include the degenerative fibers and the thickened tendon (Fig. 7-11). The tendon then is repaired with internally placed, nonabsorbable sutures with buried knots. The subcutaneous tissues are apposed, followed by closure of the skin. The leg is immobilized for 3 to 5 days in a splint, followed by range of motion exercise, strengthening, and nonimpact activities. A boot brace is worn for 6 to 12 weeks during ambulation to unload the healing tendon. Jogging and running may be introduced at 3 months, depending on the extent of involvement and the nature of the patient’s athletics.

The patient is positioned prone and both legs are prepped for any tendon transfer, turndown procedure, or V-Y advancement because it usually is necessary to compare resting tensions with those of the contralateral side. In a tendon transfer, our preferred technique is to use a medial approach to the Achilles tendon, typically staying 1 cm anterior to the medial edge of the tendon. The incision is extended more inferiorly. The paratenon is opened, the degenerative tendon is excised, and the deep fascia between the superficial and deep compartment is released. It is felt that, by opening the fascia and exposing the deeper FHL muscle belly, there is an improved vascular bed for the Achilles. Ranging the big toe should facilitate identification of the moving FHL muscle belly and tendon. The FHL tendon may have a more distal origin and may not be viewed readily in the wound. Care should be taken while dissecting along the course of the muscle because the tibial nerve runs immediately medial to the tendon (Fig. 7-12, A through E).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree