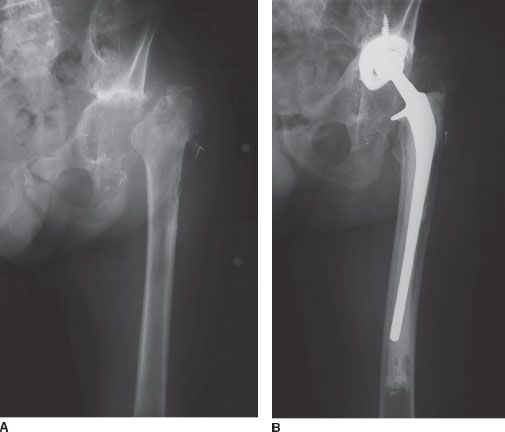

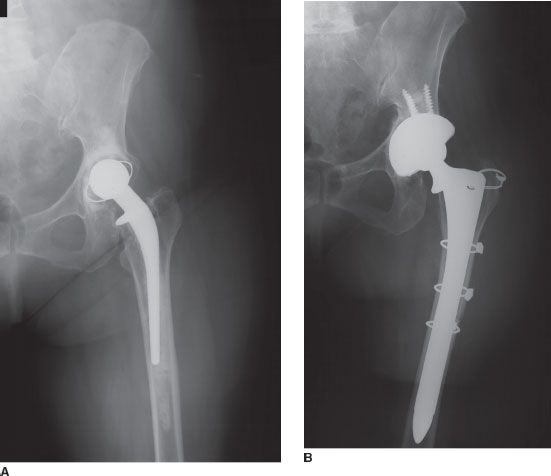

FIGURE 12-1. A: Preoperative radiograph of failed THA. B: Postoperative radiograph after reconstruction with jumbo uncemented cup.

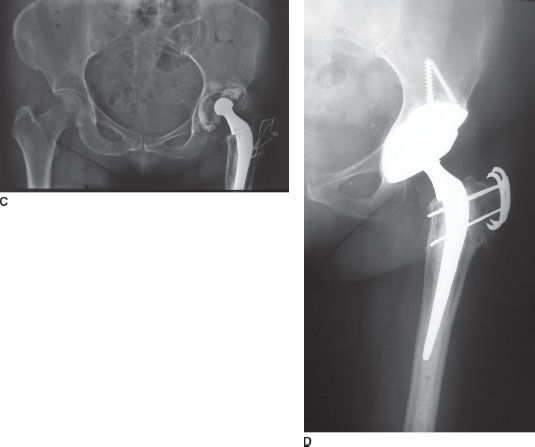

FIGURE 12-2. A: Radiograph after resection of failed infected THA. B: Postoperative radiograph after reconstruction with uncemented cup at high hip center.

When conditions are not ideal for an uncemented hemispherical acetabular component, methods to improve support of a hemispherical cup may be employed. Structural bone grafts may be used to improve initial implant stability and support. Structural bone allografts can heal to the pelvis but do not typically fully revascularize.34–36 When called on to provide prolonged support for an implant, structural grafts may be subject to fatigue failure or may be resorbed37 (possibly due to revascularization), either of which can lead to graft collapse and implant failure. Porous metal augments have been designed that can build up deficient host bone, providing further support for an uncemented hemispherical component.38 Porous metal augments do not augment bone stock but also will not resorb. Only short-term results with these devices are available.

When bone deficiency is severe, gaining stability of an uncemented hemisphere, even with bone grafting or metal augments, may not be possible. For the last several decades, antiprotrusio cages have been utilized for these difficult problems. Antiprotrusio cages have the drawbacks of not having biologic fixation surfaces, and hence being mechanical reconstructions that may be subject to long-term failure. Custom triflange porous-coated implants, which are shaped similarly to cages (with flanges on the ilium and ischium), provide a large surface area against the pelvis, and potentially allow for a porous fixation against the pelvis in cases of severe bone loss, have been used successfully in a few centers. Recently, combinations of uncemented cups supported by an antiprotrusio cage (a so-called cup-cage combination) have been used to manage some acetabular or revision problems with satisfactory short-term results.

ACETABULAR RECONSTRUCTION OPTIONS

Cemented Acetabular Components The initial method of acetabular revision was ce-mentation directly into the host bone after the removal of a failed implant. A high rate of failure occurred, probably because cement interdigitation into the sclerotic deficient bone commonly present in the revision setting was not reliable. This technique mostly has been abandoned because of high loosening rates (Fig. 12-3).

FIGURE 12-3. Failed revision THA using cemented cup. The sclerotic bone provides a poor interface for cement in most revisions.

Bipolar Hemiarthroplasty Bipolar hemiarthroplasties frequently were used in the 1980s for acetabular revisions. This method also mostly has been abandoned because of high rates of bipolar migration and pain related to articulation of the mobile bipolar implant against the pelvis (Fig. 12-4).

FIGURE 12-4. Radiograph demonstrating failure due to migration and pain of bipolar cup used for revision.

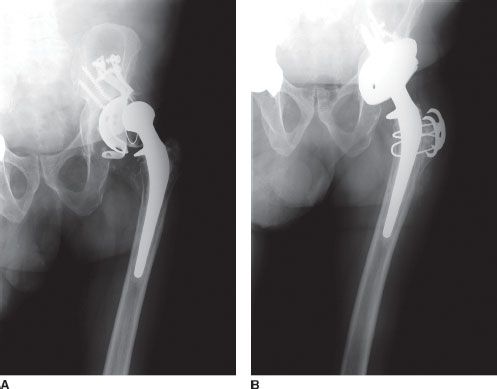

Uncemented Hemispherical Components Uncemented hemispherical acetabular com-ponents, as discussed in detail above, have become the predominant method of acetabular fixation for acetabular reconstruction during revision THA in North America (see Chapters 13 and 14). Most surgeons prefer to gain a pressfit of the component into the acetabulum and then provide extra fixation with screws (Figs. 12-5 and 12-6).

FIGURE 12-5. A: Preoperative radiograph of failed THA with acetabular loosening. B: Postoperative radiographs after routine revision with uncemented hemispherical cup.

FIGURE 12-6. A: Preoperative radiograph of failed THA. B: Postoperative radiograph after routine revision with uncemented hemispherical cup.

Impaction Bone Grafting Several European centers have demonstrated that good results can be obtained by making the acetabulum a contained space and then packing cancellous allograft bone densely into the remaining bone defects, following which an acetabular component is cemented into the bone graft.3,39–42 This technique has the advantage of potentially restoring bone stock to the acetabulum. It has the drawbacks of technically being more complex and time consuming than placement of an uncemented hemispherical component.

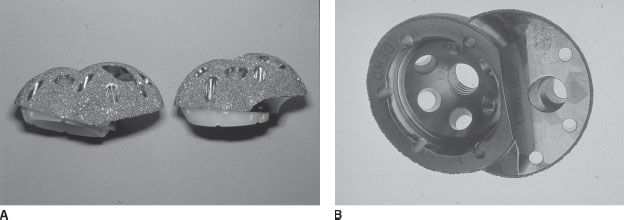

Nonhemispherical Uncemented Components Oblong or complex-geometry uncemented implants have been available from several manufacturers for many years. These implants were designed mostly to deal with Paprosky Type IIIA bone defects in which a superolateral bone defect of the acetabulum is present (Fig. 12-7). Variable results have been described with these implants.43–45 Most surgeons have found these implants difficult to use because of their complex geometry.

FIGURE 12-7. A and B: Pictures of oblong bilobed uncemented cup. C: Preoperative radiograph of failed THA with Paprosky Type IIIa bone loss. D: Postoperative radiograph 2 years after revision with uncemented bilobed acetabular component. The cup is stable and bone ingrown.

Most Paprosky Type IIIA bone deficiencies now are managed with either modular metal aug-ments or bone grafting, in combination with a modern, uncemented cup with high bone ingrowth potential. Modular metal augments can convert a hemispherical uncemented shell functionally into an oblongshaped uncemented component (see Chapter 14) (Fig. 12-8).

FIGURE 12-8. A: Failed THA with Paprosky Type IIIa bone loss. B: Revision with uncemented hemispherical cup with trabecular metal crescent-shaped augment to fill superior bone defect.

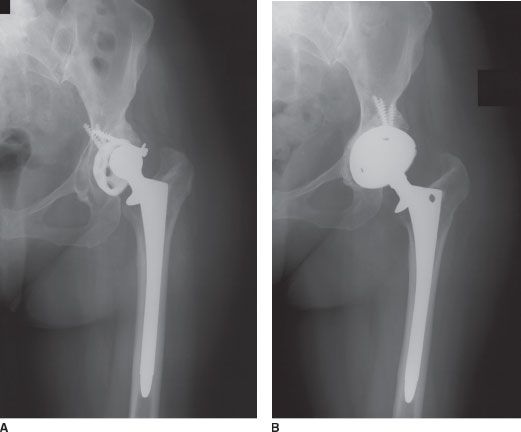

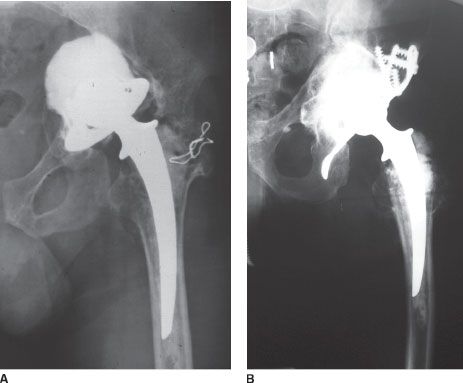

Antiprotrusio Cages Antiprotrusio rings and cages were designed several decades ago to provide a large surface area of metal against bone to resist migration in the presence of severe pelvic bone deficiency.46–48 The term antiprotrusio ring implies smaller devices with an obturator hook or flared rim, while the term antiprotrusio cage implies a device that spans from the ilium to ischium (Fig. 12-9). These implants rely for fixation on pressfit into the pelvis as well as multiple screw fixation but do not have porous surfaces because they are meant to be flexible to accommodate different pelvic shapes (Figs. 12-10 and 12-11). These implants are versatile and can be used in different types of acetabular bone loss because of their malleability (see Chapter 15).49,50 Antiprotrusio cages can be used to protect large structural allografts (Fig. 12-12).51 They suffer from the disadvantages of being bulky and difficult to insert and not providing long-term biologic fixation and, because they are malleable, being weak and at risk for fracture.52 Results from centers using cages for the most routine acetabular reconstructions have reported favorable results, but centers using them selectively for the most severe deficiencies have reported only fair mid-term results (Fig. 12-13 and 12-14). These devices are bulky and complications associated with their use are not infrequent.

FIGURE 12-9. Picture of an antiprotrusio cage.

FIGURE 12-10. A: Preoperative radiograph of failed THA with Paprosky Type IIIB bone loss. B:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree