DOCTOR:

When is Mr Brown likely to be ready to be discharged? He is walking well now and does not seem especially disabled.

PHYSIOTHERAPIST:

Yes but he is still getting stronger and will be able to walk better if he receives more therapy. His ankle dorsiflexors are still not functioning very well at all.

NURSE:

He is totally independent with self-cares.

DOCTOR:

Well then we could plan to discharge tomorrow then.

OCCUPATIONAL

THERAPIST:

He manages fine in the ward but he has stairs at home and I don’t know how well he will cope with that environment.

SOCIAL WORKER:

He wants to be home as quickly as possible and back at work because financially things are tight for his family. He is actually doing some work in hospital since most of it is computer-based.

PHYSIOTHERAPIST:

Well, what are the priorities – shouldn’t we be getting him as functional as possible? Isn’t that our job?

In this exchange, a number of words relating to the concept of ‘functioning’ are in italic. There appears to be different concepts about what this means among the different health professionals, yet many would probably agree with the physiotherapist’s belief that the primary task of rehabilitation is to maximize the person’s level of ‘functioning’. A key issue then, in order for rehabilitation teams to work productively together, is to agree upon what is meant by this important term. As we see in this hypothetical exchange, ‘functioning’ can refer to how well a person walks, the strength of a particular muscle, ability to perform a task within one environment compared with a different environment, self-care activities or actual performance of productive work.

The doctor and nurse seem to believe that accomplishment of a particular task (such as walking or self-care activities) renders the person non-disabled, irrespective of how difficult or how ‘well’ that task is managed. Furthermore, they ignore the possibility that a person can function quite well in one environment but not in another. Contextual factors are clearly more important than they realize. The occupational therapist is much more aware of the more nuanced notion of disability in which the environment can render the person disabled rather than the intrinsic abilities of the person. In such situations, improving a person’s function may have nothing to do with more therapy, but rather requires a change to the environment, such as building a ramp rather than steps. Functioning must therefore be seen as an interaction between the person and their context. One other important consideration of ‘context’, which was not raised by the team discussion, is the context of the person himself. That is, what attributes (not directly related to the issue at hand) does the client bring. This can involve his age, co-morbidities and personality traits among a range of possibilities. This context too is very important in determining the actual functioning of the person.

The social worker introduces two additional concepts. The first concerns a distinction between more basic activities such as walking and those that are more societal in orientation – fulfilling a role such as paid work or being part of a family. Accomplishing such a role may often have little relation to more basic activities, and therefore cannot be seen as hierarchical. In this example, it is simply not necessary for the person to be able to walk well in order for him to perform his paid work. Of course, in other kinds of work, walking will be a pre-requisite. But the relationship between specific disturbances of basic activities (which we might consider as those occurring at the level of the whole organism), and other kinds of activities such as work (which we might consider at the level of organism within his/her social world) cannot be assumed and needs to be evaluated carefully as part of good rehabilitation practice for each client. The second concept that the social worker introduces is the notion of ‘actual performance’ perhaps, as if this was a more impressive observation than ‘is capable of’. Certainly, the two concepts are distinct. Direct observation of performance is possible but determining capacity is rather more judgemental and involves making a prediction rather than describing what is observed. Whether observation of performance is better than prediction of capacity is unclear and almost certainly depends upon what the evaluation is used for – is it fit for purpose? Often a determination of performance is not possible, since the particular activity occurs very infrequently or is potentially dangerous. For example, how could the team respond to Mr Browns’s request for some guidance as to whether he can engage in his hobby of skydiving?

Returning to the physiotherapist again, the common use of the term ‘function’ that is synonymous with ‘operate’ means that how well or poorly parts of the organism are working also comes under the umbrella of ‘function’. Again, the relationship between the operation of parts of the organism and the whole of the organism are not necessarily hierarchical or linear. Walking is possible without all components of the walking mechanism working normally (or at all). Entire loss of a lower limb does not preclude walking. It is often critically important for therapists to consider carefully the primary targets of their treatment and to constantly re-evaluate the relevance of that target in relation to the overall rehabilitation plan.

It is clearly necessary, therefore, to organize these different concepts of ‘functioning’ into a schema that all disciplines can understand and use. We might consider this a common language of functioning where each term is precisely defined and meaningful across the different discipline-specific languages. For example, when occupational therapists talk about the ‘Model of Human Occupation’ (Kielhofner, 2008), can the language be translated into the same terms that psychologists would use when discussing ‘cognitive–behavioural therapy’?

From the perspective of populations, healthcare systems and payers such a language is also important. For example, a means of how to classify, categorize and enumerate all the ways people are affected by health conditions is necessary in order to properly understand the health and functioning of a population. A descriptive language that contains all the manifestations of health and disease would be complementary to a descriptive system of pathological diagnoses contained within the International Classification of Disease (ICD) (WHO, 1992).

This chapter discusses such a language. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) introduced by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2001 was a landmark achievement towards comprehensively understanding and describing ‘functioning’ (Ustun et al., 2003). With this language, it is now possible for different disciplines to understand what each other does and begin to form rational commonalities across discipline-specific models of thinking. Furthermore, an acceptable language of functioning enables a more scientific discourse to determine the nature of functioning in its totality and in its component parts. The better way of describing functioning that the ICF provides can permit an investigation into the connections between its component parts, the determinants of functioning and the effectiveness of interventions that might improve functioning. It may not be overstating the case to say that the ICF is a central pillar of rehabilitation theory and practice.

This chapter will describe the origin of the ICF, describe the ICF in more detail, explain the core set and other approaches to making the ICF more usable, and how the ICF relates to measurement of functioning and health status. We will discuss some difficulties with the ICF – in particular how it relates to quality of life (QoL) – and the distinctions between some components of the ICF. And finally we consider some possible developments for the future of the ICF.

2.2 The ICF is both a model and a classification system

Introduction

The endorsement of the ICF (WHO, 2001) by the World Health Assembly in May 2001 was a milestone that gave important impetus to health services provision and research, especially to the field of rehabilitation (Stucki et al., 2002). Traditionally, functioning and disability have been considered as the result or consequence, caused and fully determined by disease or injury. This idea is expressed by the so-called medical or bio-medical model (Boorse, 1975, 1977). However, functioning and disability are more complex than this. In reality it is apparent that the disease or injury (described by a diagnosis) is not sufficient to determine the functioning and disability of individuals (WHO, 2002). Two people with the same diagnosis can often have different levels of functioning and disability, whereas a similar pattern of functioning and disability may result from different aetiologies. For example, a rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament will lead to different consequences for a 28-year-old professional soccer player compared with a 64-year-old grandmother living on the fourth floor of a building without an elevator. A diagnosis alone does not sufficiently explain, for example, length of hospital stay, the required amount of nursing care or therapy applications. A diagnosis of a pathological process does not describe an individual person’s level of persistent disability, his or her ability to return to work, or the potential for community reintegration.

Healthcare planning, management, evaluation and funding, in the clinical, institutional or policy context, needs more information beyond the diagnosis. The ICF has been developed to complement the diagnostic information. A standardized systematic terminology has been available for diseases for over a hundred years, namely the most recent version of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10, WHO, 1992). In contrast, the ICF as a globally agreed common language and a framework for the description of the components of health, functioning and disability was first published in 2001. Whereas detailed statistics on prevalence, incidence and mortality of diseases are available, much less is known about the health states of people with chronic conditions and the survivors of acute events, like stroke or spinal cord injury.

The ICF is both a basic model for the comprehensive understanding of health and health-related states and the classification that implements the model and provides a multipurpose, systematic and universal language to describe a wide range of health-related phenomena.

The ICF as a model

The ICF is based upon a comprehensive biopsychosocial model, which integrates different perspectives of health into one unified and coherent view. What does this mean? The model is comprehensive as it includes various dimensions, i.e. it considers disability not only from a physical, but also from an individual and societal perspective, and importantly includes the environmental and personal context of the individual. It is integrative as it combines biomedical, psychological as well as social views of disability.

Table 2.1 The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) components and their definitions.

| Parts | Components | Definition |

| Health condition | Health condition | disease (acute or chronic), disorder, injury or trauma |

| Functioning and disability | Body functions | are the physiological functions of body systems |

| Body structures | are anatomical parts of the body such as organs, limbs and their components | |

| Impairments | are problems in body function or structure such as a significant deviation or loss | |

| Activity | is the execution of a task or action by an individual | |

| Activity limitations | are difficulties an individual may have in executing activities | |

| Participation | is involvement in life situation | |

| Participation restrictions | are problems an individual may experience in involvement in life situations | |

| Contextual factors | Environmental factors | make up the physical, social and attitudinal environment in which people live and conduct their lives |

| Personal factors | are the particular background of an individual’s life and living, and comprise features of the individual that are not part of a health condition or health states |

Components of the ICF model

The biopsychosocial model consists of three parts: (1) the health condition, (2) functioning with its three main components, and (3) the two contextual factors. The model comprises six building blocks, which address the six components of health: the health condition, body functions and structures, activity, participation, environmental factors and personal factors. These components taken together provide a full picture of functioning, disability and health. The ICF presents definitions for all of these components, which are shown in Table 2.1.

Health condition refers to any kind of disorder or disease, but also to further phenomena, e.g. trauma, congenital anomalies, genetic predispositions or ageing. Functioning embraces three dimensions that refer to different perspectives, namely, the perspective of the human body, of the whole individual and of society. The first dimension, representing the level of the body, includes body functions and body structures. Body functions are the physiological functions of body systems, also including mental functions. Body structures are the anatomical parts of the body. Activity represents the individual perspective of functioning. Activity is described as the execution of a task or action by an individual as an independent subject. Participation is the involvement of the individual in life situations. It represents the societal perspective of functioning.

The contextual factors include the environmental factors and the personal factors. Environmental factors refer to the physical, social and attitudinal environment that form the context of an individual’s life and, as such, have an impact on the person’s functioning. Personal factors are contextual factors that make up the particular background of an individual’s life and living, but are not part of the health condition or health states. For example, age, gender, social status, life experiences, personality, etc.

The central concepts of the biopsychosocial model are functioning and disability. Functioning is an umbrella term for intact body functions and structures, activities and participation. Functioning denotes the positive or neutral outcome of the bidirectional complex interaction between an individual’s health condition and his or her context. The complementary term disability is an umbrella term to denote impairments of body functions and structures, activity limitations or participation restrictions, which are the negative aspects of the named interaction.

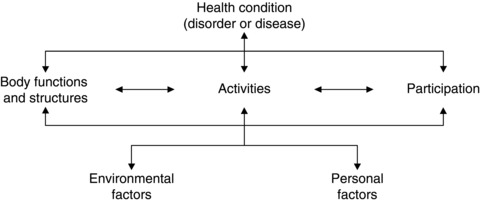

The current understanding of the interactions of the components of functioning, disability and health within the biopsychosocial approach is depicted in Figure 2.1. It is important to note that the components of the ICF model relate to each other in a complex bidirectional way, as opposed to a linear–causal type of relationship.

- Health condition: rheumatoid arthritis

- Body structures and functions : pain, deformity and impaired movement of several joints

- Activity limitations: gripping difficulties, walking long distances

- Participation restrictions: none

- Environmental factors: supportive employer

- Personal factors: determined and well-balanced personality

The ICF as a classification

The integrative biopsychosocial framework of the ICF is implemented in the according classification. The classification is the flesh to the skeleton of the model framework. The common idea of the model is represented by the standardized language or terminology of the classification.

The ICF as a classification is a listing of categories that fully describes the various aspects of functioning and the environment, organized within components. The categories are structured in a hierarchically nested way. Each component consists of chapters (categories at the first level), each chapter consists of second-level categories, and in turn they are made up of categories at the third and fourth levels. The ICF provides categories for the different kinds of body functions, a list of body structures, a joint list of activities and participations, and a list of environmental factors. An example to illustrate the nested structure of the ICF is presented in Table 2.2.

Figure 2.1 The biopsychosocial model of functioning, disability and health. (With permission from the World Health Organization see http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/)

Table 2.2 The nested structure of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF).

| Code | Category | Level |

| b | Body functions | |

| b1 | Mental functions | (first/chapter level) |

| b114 | Orientation functions | (second level) |

| b1142 | Orientation to person | (third level) |

| b11420 | Orientation to self | (fourth level) |

| b11421 | Orientation to others | (fourth level) |

Table 2.3 shows the available chapters of the ICF. The 30 chapters include overall 1424 categories at the second, third and fourth levels. The categories are accompanied by definitions, examples, inclusion and exclusion criteria. The total list can be viewed using the Manual available from the WHO or by using the online ICF browser (http://apps.who.int/classifications/icfbrowser/).

Personal factors are not yet implemented as a part of the classification. Moreover, health conditions are not classified by the ICF, but are classified by another member of the WHO family of international classifications, the ICD-10 (WHO, 1992).

The ICF states that the description of the functioning of a person is not complete without adding to the ICF categories the so called ‘qualifiers’. The qualifiers denote the extent of impairments, limitations and restrictions. They quantify the level of functioning and health or the severity of the problem in the different ICF categories. The WHO proposes that all categories of the classification are to be quantified using the same generic scale ranging from 0 (no problem) to 4 (complete problem). In the component of the environmental factors, the qualifiers denote the extent to which a certain factor is a facilitator or a barrier to the functioning of the person. Accordingly, the qualifier scale extends from +4 to –4.

Table 2.3 The chapters of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF).

| Code | Component and chapter titles |

| b | BODY FUNCTIONS |

| b1 | Mental functions |

| b2 | Sensory functions and pain |

| b3 | Voice and speech functions |

| b4 | Functions of the cardiovascular, haematological, immunological and respiratory systems |

| b5 | Functions of the digestive, metabolic and endocrine systems |

| b6 | Genitourinary and reproductive functions |

| b7 | Neuromusculoskeletal and movement-related functions |

| b8 | Functions of the skin and related structures |

| s | BODY STRUCTURES |

| s1 | Structures of the nervous system |

| s2 | The eye, ear and related structures |

| s3 | Structures involved in voice and speech |

| s4 | Structures of the cardiovascular, immunological and respiratory systems |

| s5 | Structures related to the digestive, metabolic and endocrine systems |

| s6 | Structures related to the genitourinary and reproductive systems |

| s7 | Structures related to movement |

| s8 | Skin and related structures |

| d | ACTIVITY AND PARTICIPATION |

| d1 | Learning and applying knowledge |

| d2 | General tasks and demands |

| d3 | Communication |

| d4 | Mobility |

| d5 | Self-care |

| d6 | Domestic life |

| d7 | Interpersonal interactions and relationships |

| d8 | Major life areas |

| d9 | Community, social and civic life |

| e | ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS |

| e1 | Products and technology |

| e2 | Natural environment and human-made changes to environment |

| e3 | Support and relationships |

| e4 | Attitudes |

| e5 | Services, systems and policies |

According to the WHO, broad ranges of percentages are provided for those cases in which calibrated assessment instruments or other standards are available to quantify the impairment, activity limitation, participation restriction or environmental barrier/facilitator. Table 2.4 shows the generic qualifier scale of the ICF. It is to be noted, that the generic qualifier scale is one option among others provided by the ICF, which also offers further options, especially for the coding of activities and participation, but also environmental factors. These further options are described in the ICF’s Annex 2 and 3 (WHO, 2001).

Table 2.4 The generic International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) qualifier scale.

| Qualifier | Description | |

| Functioning | Impairment, restriction, limitation, % | |

| 0 | NO problem (none, absent, negligible…) | 0–4 |

| 1 | MILD problem (slight, low…) | 5–24 |

| 2 | MODERATE problem (medium, fair…) | 25–49 |

| 3 | SEVERE problem (high, extreme…) | 50–95 |

| 4 | COMPLETE problem (total…) | 96–100 |

| 8 | Not specified | |

| 9 | Not applicable | |

| Environmental factors | Barrier, facilitator | |

| 0 | NO barrier or facilitator | 0–4 |

| 1 | MILD barrier | 5–24 |

| 2 | MODERATE barrier | 25–49 |

| 3 | SEVERE barrier | 50–95 |

| 4 | COMPLETE barrier | 96–100 |

| +1 | MILD facilitator | 5–24 |

| +2 | MODERATE facilitator | 25–49 |

| +3 | SUBSTANTIAL facilitator | 50–95 |

| +4 | COMPLETE facilitator | 96–100 |

| 8 | Barrier or facilitator: not specified | |

| 9 | Not applicable | |

2.3 The origins of the ICF

Models of disability help us in defining what disability is and how we can think and speak about it. The question ‘what is disability?’ is not new and the ICF was not the first approach to thinking about a model for disability. On the contrary, the ICF as a model can be viewed as the intermediate product of a ‘quasi-evolutionary’ development of disability models (Masala and Petretto, 2008; McDougall et al., 2010; Whiteneck, 2005). It integrates various lines of thought about disability into a ‘meta-model’.

There are two principle strands of development that came together to form the ICF. The first has been called the ‘medical model’ derived from a concept of disability, which is that disability is the consequence of disease or injury in an individual. It should be noted that ‘medical’ in this sense does not necessarily refer to a single professional group, but to a way of thinking in which everything is explained by pathology (some kind of deviation from normal). The second strand is the ‘social model’, which considers that disability is primarily due to society’s inability or difficulty in accommodating the particular needs and requirements of people with impairments.

The medical model strongly influenced the development of the WHO 1980 International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicaps (ICIDH) by Philip Wood, the precursor to the ICF (Kostanjsek et al., 2009). Possibly, the defining characteristic of the medical model is that disability is seen as a deficit of the individual, amenable to an ‘expert’ solution, leading to a restoration of optimal functioning to which all people aspire. For example, the definition of disability offered by Nagi (1964), which was highly congruent with the development of the ICIDH, was: ‘Inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity by reason of a medically determinable impairment that is expected to be of long-continued and indefinite duration or to result in death’ (Nagi, 1964).

It should be clearly noted that Nagi also recognized that ‘inability’ could be due to the environmental context alone, which presaged later developments of the ICF, but this original framework provided by Nagi distinguished the concepts of pathology, impairment, functional limitation and disability, which related to each other in a linear–causal way. This Functional Limitation Model became the most influential formulation of the biomedical understanding of disability over the following decades, and a number of subsequent models have built upon Nagi’s framework, e.g. models by the Institutes of Medicine in the USA, the ICIDH-model of the WHO, the Disability Creation Process model of the Quebec Group in Canada (Fougeyrollas et al., 1998; Institute of Medicine et al., 1991, 1997; World Health Organization, 1980).

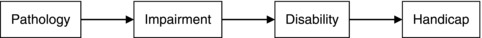

Viewed from this perspective, there is a linear, hierarchical progression of the consequences of pathology (Figure 2.2). The principal components of this model are conceived in negative terms; ‘impairment’ is a deficit of organ function, ‘disability’ is a deficit of functioning at the level of the whole person, ‘handicap’ is a deficit of functioning at the level of society.

Although this model represented a significant advance over a purely ‘disease’ based concept of health in which health equated with absence of disease, there are clearly many shortcomings. The nature of the language was seen as pejorative, the focus on a normative concept of disability conflicted significantly with a social model of disability and the idea that a linear, causal relationship exists between the components of the model was simplistic and inaccurate (Chatterji et al., 1999; Ustun et al., 1995). Nevertheless, the concept of separating out the manifestations of dysfunction by reference to the distinctions between organ (impairment), the whole organism (disability) and the organism’s relation to other organisms (handicap) was fundamental and continues to inform current thinking about disability and health. This concept remains the crowning achievement of the ICIDH.

In contrast, the ‘social model’ of disability was generated outside of the health arena from the disability rights movement of the 1960s. The term itself appears to have first been used by Mike Oliver in 1983, to describe the view articulated by the UK Organisation Union of the Physically Impaired against Segregation (UPIAS), which was: ‘In our view it is society which disables physically impaired people. Disability is something imposed on top of our impairments by the way we are unnecessarily isolated and excluded from full participation in society’ (UPIAS, 1975).

Figure 2.2 The International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicaps (ICIDH) model.

From this perspective, disability is created by the failure of society to accommodate to the requirements of all its members (especially minority groups) rather than by failure of individuals to accommodate to the requirements of society. Whereas impairment might be related to health problems, disability only relates to society’s response to those impairments. Hence, health (and the health professional) is largely irrelevant to the disabled person.

The biopsychosocial model brings these streams of thought together, although George Engel’s original conception of the term in 1977 was influenced more by medicine’s inappropriate reliance upon the biological sciences, especially molecular biology, than consideration of the phenomenon of disability (Engel, 1977). Yet the systems theory approach he proposed has been very influential upon the evolution of the ICIDH into the ICF, especially in moving away from a linear, cause and effect kind of thinking that solely focuses upon the body and disease: ‘This approach, by treating sets of related events collectively as systems manifesting functions and properties on the specific level of the whole, has made possible recognition of isomorphies across different levels of organisation, as molecules, cells, organs, the organism, the person, the family, the society, or the biosphere’ (Engel, 1977, p. 134).

The ICF does not go so far as to conceive of the biosphere, but the identification of the distinct elements of health conditions (pathology), body structures, body functions, activity limitations, participation restrictions, environmental factors and personal factors that may relate to each other in many different ways (these relationships are not assumed) is a systems approach to considering the concept of ‘functioning’.

2.4 Using the ICF in practice – ICF core sets, rehabilitation cycle and ICF tools

Introduction

The ICF can be used in different settings and for various purposes, at individual and also at population levels, e.g. for research, health statistics, disability evaluation, education, and policy. In clinical rehabilitation, the ICF (WHO, 2001) can be applied together with the ICD to individuals with specific health conditions. The ICF is a highly comprehensive classification containing more than 1400 categories to describe people’s functioning, disability and health. This comprehensiveness is a major advantage and strength of the ICF. But at the same time it is a major challenge to its practicability and feasibility.

For specific applications, especially in clinical practice, tailored tools need to be available, which simplify the use of the ICF and at the same time take advantage of its strengths. A number of such tools are currently available. First of all, the ICF core sets are named (these are discussed in detail in the following section), as they build the basis for further tools (Cieza et al., 2004a; Stucki et al., 2002, 2003). Further clinical ICF application tools are embedded in the model of the rehabilitation cycle: the ICF assessment sheet, the ICF categorical profile and evaluation display and the intervention table (Rauch et al., 2008, 2010a, 2010b; Steiner et al., 2002; Stucki et al., 2002; Swiss Paraplegic Research, 2007).

ICF core sets

The development of the ICF core sets is one approach to enhance the applicability of the ICF (Cieza et al., 2004a). This approach, in line with the underlying biopsychosocial model, explicitly connects functioning and disability categories, which are aetiologically neutral, to a defined health condition (or diagnosis) to facilitate data collection. The WHO has recognized that in everyday practice and in specific settings, only a fraction out of the total number of the ICF’s categories is needed (Ustun et al., 2004). Thus, an ICF core set is a selection of categories out of the entire classification, which describe in a parsimonious way the functional impact of a certain specified health condition.

Scientifically based internationally agreed ICF core sets for a number of health conditions have been developed in WHO collaborative projects together with partner organizations worldwide. A selection of already available ICF core sets is listed in Table 2.5. For each of the health conditions two types of ICF core sets have been developed. Comprehensive ICF core sets include the prototypical spectrum of functioning problems in people with the given condition, to be used in multidisciplinary settings as a basis for comprehensive assessment and documentation. The brief ICF core sets serve in clinical encounters, but also in clinical and epidemiological studies or in health reporting, as minimum data-sets and represent a selection out of the corresponding comprehensive ICF core set. Using the universal terminology of the ICF, ICF core sets preserve all advantages and potentials of the classification as a common standard language, enhancing its feasibility at the same time by their manageable size.

The development of an ICF core set is an international process, conducted according to a standardized protocol in collaboration with WHO and partner organizations. The methodology integrates scientific evidence as well as consensus elements (Biering-Sorensen et al., 2006, ICF core set SCI). The development is basically a filtering process and consists overall of three phases: (1) preliminary studies, (2) consensus conference, and (3) validation and testing.

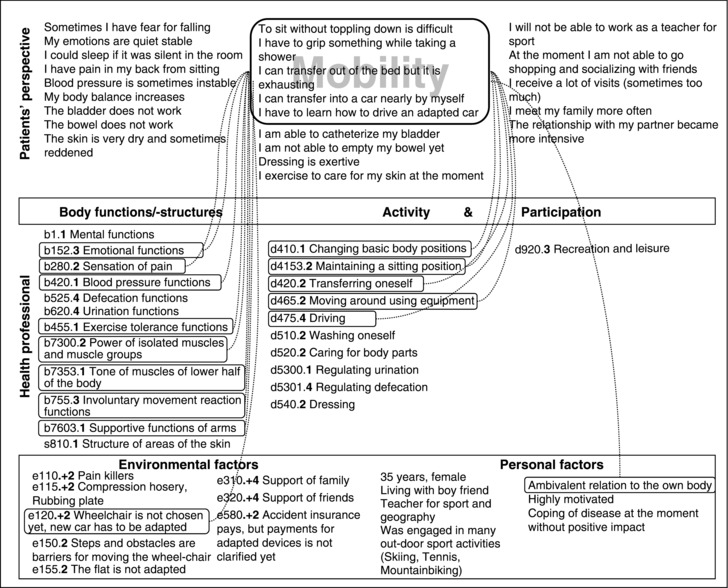

The preliminary studies use a triangulation approach and consider the consumer’s perspective, the health professionals’ and the clinical as well as the research perspective. The standard protocol includes qualitative focus group studies with service users, web-based expert surveys with health professionals from various disciplines, extensive empirical data collections using the ICF and systematic reviews of the literature. From these preliminary studies, a broad pool of ICF categories is pre-selected. The pre-selected categories are potential candidates to be included in the ICF core set.

Table 2.5 International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) core sets for specific health conditions.

| ICF core sets | References |

| Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) | Boonen et al. (2010), ICF core set AS |

| Bipolar disorders | Vieta et al. (2007), ICF core set Bipolar |

| Breast cancer | Brach et al. (2004), ICF core set BC |

| Chronic ischemic heart disease (CIHD) | Cieza et al. (2004b), ICF core set CIHD |

| Chronic widespread pain (CWP) | Cieza et al. (2004c), ICF core set CWP; Hieblinger et al. (2009), ICF core set CWP |

| Depression | Cieza et al. (2004d), ICF core set Depression |

| Diabetes mellitus (DM) | Ruof et al. (2004), ICF core set DM; Kirchberger et al. (2009), ICF core set DM |

| Head and neck cancer (HNC) | Tschiesner et al. (2007), ICF core set HNC; Tschiesner et al. (2009), ICF core set HNC; Becker et al. (2010), ICF core set HNC; Tschiesner et al. (2010), ICF core set HNC |

| Low back pain (LBP) | Cieza et al. (2004e), ICF core set LBP; Roe et al. (2009), ICF core set LBP |

| Multiple sclerosis (MS) | Khan and Pallant (2007a, 2007b), ICF core set MS; Kesselring et al. (2008), ICF core set MS |

| Obesity | Stucki et al. (2004a), ICF core sets Obesity; Raggi et al. (2009), ICF core set Obesity |

| Obstructive pulmonary diseases (OPD) | Stucki et al. (2004b), ICF core set OPD; Rauch et al. (2009), ICF core set OPD |

| Osteoarthritis (OA) | Dreinhofer et al. (2004), ICF core set OA; Xie et al. (2007), ICF core set OA |

| Osteoporosis (OP) | Cieza et al. (2004f), ICF core set OP |

| Psoriasis | Taylor et al. (2010), ICF core set PsA |

| Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) | Taylor et al. (2010), ICF core set PsA |

| Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) | Stucki et al. (2004c), ICF core set RA; Coenen et al. (2006), ICF core set RA; Kirchberger et al. (2007), ICF core set RA; Uhlig et al. (2007), ICF core set RA; Uhlig et al. (2009), ICF core set RA |

| Sleep disorders | Gradinger et al. (2009), ICF core set Sleep |

| Spinal cord injury (SCI) | Biering-Sorensen et al. (2006), ICF core set SCI; Cieza et al. (2010), ICF core set SCI; Kirchberger et al. (2010), ICF core set SCI |

| Stroke | Geyh et al. (2004), ICF core set Stroke; Starrost et al. (2008), ICF core set Stroke; Alguren et al. (2010), ICF core set Stroke; Lemberg et al. (2010), ICF core set Stroke |

| Systemic lupus erythematosis &systemic sclerosis | Aringer et al. (2006), ICF core set Lupus |

| Traumatic brain injury (bodycellI) | Aiachini et al. (2010), ICF core set bodycellI |

The ICF categories, which resulted from the phase 1 preliminary studies, enter the consensus process. In phase 2, for each health condition, an international consensus conference takes place with representatively selected experts from different world regions and different professional backgrounds. The consensus conference follows a structured nominal group process with discussion and voting rounds according to predefined procedures and decision criteria. The comprehensive and the brief ICF core sets are the final output of phase 2. These short lists of ICF categories to be used in a certain health condition are validated and tested in phase 3, in national as well as international efforts from different perspectives. Phase 3 is an open-ended process that continuously provides information to the users about the ICF core sets in various settings.

Figure 2.3 International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) assessment sheet. The ICF codes in the health professional’s section are composed of the ICF category and the ICF qualifier (marked here in bold). (Designed by and reproduced with permission from William Levack.)