PROCEDURE 33 Knee Surgery for Children with Cerebral Palsy I: Hamstring Lengthening Benjamin J. Shore and Brian Snyder • As a child with cerebral palsy matures, incongruous growth between the muscle and bone occurs so that the muscle is relatively shorter than the bone it subtends. Biarticular muscles tend to be more affected than monoarticular muscles; this pattern appears to be more profound distally than proximally, resulting in contractures of the gastrocnemius-soleus, hamstrings, rectus femoris, and psoas muscles. • Spasticity is the most common abnormality of muscle seen in patients with cerebral palsy. The hallmark feature of spasticity is velocity-dependent stiffness of the muscle in proportion to the rate of muscle stretch, indicating a loss of central nervous system inhibition. • The increased muscle tone can induce abnormal movement patterns and frequently leads to the progressive development of muscle-tendon contractures and skeletal abnormalities, including torsional bone deformities and joint instability. • Surgical results are optimized when the timing of surgery is delayed until children have reached a functional “plateau.” At this point, the child has exhausted nonsurgical measures (physical therapy, orthoses, and pharmacologic spasticity management), has failed to demonstrate significant improvement over a 6-month follow-up period, and experiences significant functional impairments affecting ambulation and activities of daily living. • Gait analysis is an important component of the surgical decision-making algorithm for children with cerebral palsy. Quantitative gait analysis can provide objective information regarding deviations in three-dimensional joint kinematics involving multiple joints simultaneously and often provides additional information to the surgeon beyond that ascertained by physical examination alone. • Stiff-knee gait, which was previously described by Sutherland and Davids (1993) and represents the delayed and decreased dynamic knee flexion amplitude during the swing phase of the gait cycle, was seen across three of the four gait patterns described by Rhodda et al. (2004). As a result, it was considered to be a specific knee pattern but not a specific gait pattern. • In light of these specific gait patterns and their implications for treatment affecting functional outcomes, it is important for the treating orthopedic surgeon to carefully examine the hip and ankle when considered knee surgery in children with cerebral palsy. • The patient is placed in supine, with the pelvis positioned such that the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) is vertically aligned with the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS), and lumbar lordosis is reduced. • One hip is flexed to 90° and the contralateral leg is assessed in full extension. • Any flexion of the contralateral leg indicates the presence of a hip flexion contracture. • If there is a concomitant knee flexion contracture, the patient is positioned so that the leg extends beyond the end of the examination table to accommodate the knee flexion contracture. • The patient is positioned in supine with one hip flexed to 90° and the contralateral leg extended. • Initially the ipsilateral knee is flexed to greater than 90° and then slowly the knee is extended until the first endpoint of resistance is felt and the pelvis begins to “rock”; the measurement (in degrees) lacking full extension is the KPA (Fig. 3). • The unilateral KPA is a measure of “functional hamstring contracture.” Functional KPA ranges from 0 to 49° (Katz et al., 1992); angles greater than 50° require surgical intervention. • The bilateral KPA is determined with the contralateral hip flexed until the ASIS and PSIS are in a vertical line, decreasing lumbar lordosis and pelvic tilt. The bilateral KPA gives a measure of “true hamstring contracture.” • The difference between the unilateral and the bilateral KPA is the “hamstring shift.” Hamstring shift greater than 20° indicates significant anterior pelvic tilt from (Delp et al., 2006):

Knee Surgery for Children with Cerebral Palsy

Introduction

Children with cerebral palsy demonstrate three primary abnormalities of gait: (1) loss of selective motor control, (2) impaired balance, and (3) abnormal muscle tone.

Children with cerebral palsy demonstrate three primary abnormalities of gait: (1) loss of selective motor control, (2) impaired balance, and (3) abnormal muscle tone.

The goal of surgery for children with cerebral palsy is to improve overall function by addressing structural bone deformities, muscle-tendon contractures, and lever arm dysfunction.

The goal of surgery for children with cerebral palsy is to improve overall function by addressing structural bone deformities, muscle-tendon contractures, and lever arm dysfunction.

In our clinic, preoperative analysis includes physical examination, observational gait analysis, and frequently quantitative three-dimensional computerized motion analysis.

In our clinic, preoperative analysis includes physical examination, observational gait analysis, and frequently quantitative three-dimensional computerized motion analysis.

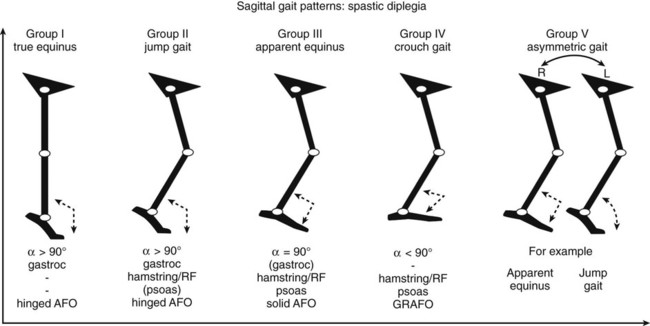

Different gait patterns involving the knee have been described in ambulatory children with cerebral palsy. Most recently, Rhodda et al. (2004) identified four gait patterns in children with spastic diplegia and outlined surgical and nonsurgical treatment for each pattern (Fig. 1).

Different gait patterns involving the knee have been described in ambulatory children with cerebral palsy. Most recently, Rhodda et al. (2004) identified four gait patterns in children with spastic diplegia and outlined surgical and nonsurgical treatment for each pattern (Fig. 1).

True equinus gait occurs when the ankle is fixed in equinus but the knee, hip, and pelvis demonstrate a normal dynamic range of motion.

True equinus gait occurs when the ankle is fixed in equinus but the knee, hip, and pelvis demonstrate a normal dynamic range of motion.

Jump gait occurs when the ankle is fixed in equinus, and the hip and knee demonstrate a flexed posture in early stance and extend to a variable degree in late stance, yet never reach full extension.

Jump gait occurs when the ankle is fixed in equinus, and the hip and knee demonstrate a flexed posture in early stance and extend to a variable degree in late stance, yet never reach full extension.

Apparent equinus gait occurs when the ankle has a normal dynamic range of motion but the hip and knee demonstrate increased flexion throughout the stance phase so that the patient appears to be up on his or her toes; often the pelvis may be tilted anteriorly (contracted psoas muscle).

Apparent equinus gait occurs when the ankle has a normal dynamic range of motion but the hip and knee demonstrate increased flexion throughout the stance phase so that the patient appears to be up on his or her toes; often the pelvis may be tilted anteriorly (contracted psoas muscle).

Crouch gait is defined as calcaneus or hyperdorsiflexion of the ankle with increased flexion at the hip and knee throughout stance; the pelvis may be tilted posteriorly (hamstring contracture).

Crouch gait is defined as calcaneus or hyperdorsiflexion of the ankle with increased flexion at the hip and knee throughout stance; the pelvis may be tilted posteriorly (hamstring contracture).

Surgical treatment of knee pathology in children with cerebral palsy rarely involves isolated muscle-tendon lengthening. This procedure highlights two of the surgical techniques commonly employed to treat knee pathology relative to the observed gait disturbances in children with cerebral palsy: hamstring lengthening and distal rectus femoris transfer (see Knee Surgery in Children with Cerebral Palsy II).

Surgical treatment of knee pathology in children with cerebral palsy rarely involves isolated muscle-tendon lengthening. This procedure highlights two of the surgical techniques commonly employed to treat knee pathology relative to the observed gait disturbances in children with cerebral palsy: hamstring lengthening and distal rectus femoris transfer (see Knee Surgery in Children with Cerebral Palsy II).

Examination/Imaging

Observational gait analysis is important in assessing which of the four gait patterns is present.

Observational gait analysis is important in assessing which of the four gait patterns is present.

The hip is examined for the presence of hip flexion contracture with the Thomas test.

The hip is examined for the presence of hip flexion contracture with the Thomas test.

The knee is examined for hamstring tightness and the presence of fixed knee flexion contracture.

The knee is examined for hamstring tightness and the presence of fixed knee flexion contracture.

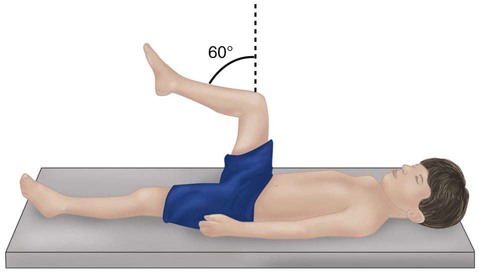

The knee-popliteal angle (KPA) is an effective tool to assess hamstring length (Fig. 2).

The knee-popliteal angle (KPA) is an effective tool to assess hamstring length (Fig. 2).

Examination for fixed knee flexion contracture is preformed with the patient prone, feet overhanging the edge of the examination table. Any lack of full knee extension indicates persistent knee flexion contracture.

Examination for fixed knee flexion contracture is preformed with the patient prone, feet overhanging the edge of the examination table. Any lack of full knee extension indicates persistent knee flexion contracture.

Surgical Anatomy

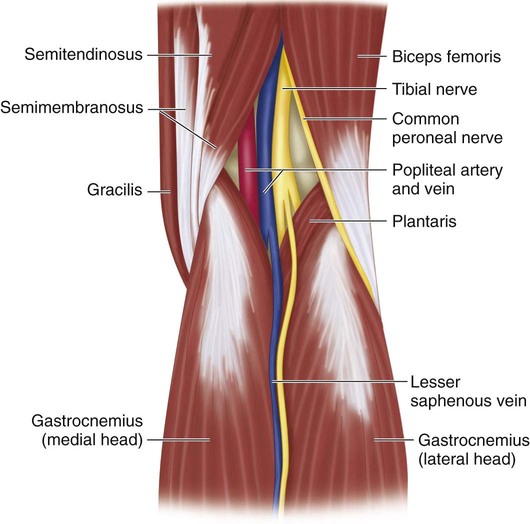

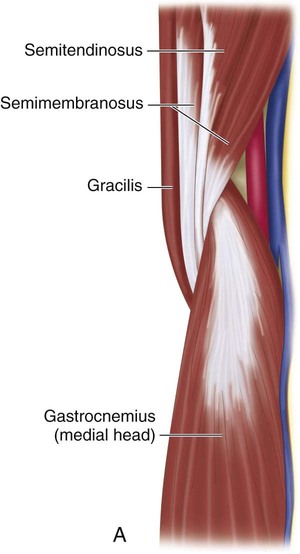

The semitendinosus, gracilis, and semimembranosus make up the medial-side hamstring muscles that commonly insert onto the pes anserinus of the proximal medial tibia (Fig. 4).

The semitendinosus, gracilis, and semimembranosus make up the medial-side hamstring muscles that commonly insert onto the pes anserinus of the proximal medial tibia (Fig. 4).

Superficially and medial to the midline lies the semitendinosus, which is palpable as a tight tendon just proximal to the popliteal crease. At this level, the semitendinosus is purely tendinous with no visible muscle belly.

Superficially and medial to the midline lies the semitendinosus, which is palpable as a tight tendon just proximal to the popliteal crease. At this level, the semitendinosus is purely tendinous with no visible muscle belly.

Deep and medial to semitendinosus lie the semimembranosus and gracilis. The gracilis is the most medial of the three muscles and can be tightened with abduction of the hip and extension at the knee. At this level, the tendon of the gracilis is intramuscular, lying on the anteromedial aspect of the muscle belly.

Deep and medial to semitendinosus lie the semimembranosus and gracilis. The gracilis is the most medial of the three muscles and can be tightened with abduction of the hip and extension at the knee. At this level, the tendon of the gracilis is intramuscular, lying on the anteromedial aspect of the muscle belly.

The semimembranosus lies deep to the semitendinosus and gracilis and demonstrates a broad muscular attachment with five separate insertions on the back of the knee.

The semimembranosus lies deep to the semitendinosus and gracilis and demonstrates a broad muscular attachment with five separate insertions on the back of the knee.

The medial intermuscular septum lies deep between the interval of the semimembranosus and gracilis. A 10-cm window through this septum is opened longitudinally to facilitate transfer of the rectus femoris to the semitendinosus/gracilis or semitendinosus transfer around the adductor magnus tendon.

The medial intermuscular septum lies deep between the interval of the semimembranosus and gracilis. A 10-cm window through this septum is opened longitudinally to facilitate transfer of the rectus femoris to the semitendinosus/gracilis or semitendinosus transfer around the adductor magnus tendon.

The adductor magnus muscle forms a discrete tendon that inserts on the adductor tubercle on the medial femoral condyle and lies anterior to the medial intermuscular septum.

The adductor magnus muscle forms a discrete tendon that inserts on the adductor tubercle on the medial femoral condyle and lies anterior to the medial intermuscular septum.

The biceps femoris lies on the lateral border of the popliteal fossa. This tendon can be palpated proximal to the popliteal crease. Medial to the biceps femoris (lateral to medial) lie the common peroneal nerve, tibial nerve, popliteal vein, and popliteal artery (see Fig. 4).

The biceps femoris lies on the lateral border of the popliteal fossa. This tendon can be palpated proximal to the popliteal crease. Medial to the biceps femoris (lateral to medial) lie the common peroneal nerve, tibial nerve, popliteal vein, and popliteal artery (see Fig. 4).

The common peroneal nerve lies along the posterior/medial border of the biceps femoris and can be difficult to isolate from the muscle-tendon junction of the biceps femoris in very contracted knees (see Fig. 4).

The common peroneal nerve lies along the posterior/medial border of the biceps femoris and can be difficult to isolate from the muscle-tendon junction of the biceps femoris in very contracted knees (see Fig. 4).

Positioning

The patient is examined under general anesthesia and physical examination findings are compared to those when awake. The differences may be attributed to spasticity that requires pharmacologic tone management.

The patient is examined under general anesthesia and physical examination findings are compared to those when awake. The differences may be attributed to spasticity that requires pharmacologic tone management.

When considering positioning, the surgeon should always assess for the presence of hip flexion contracture.

When considering positioning, the surgeon should always assess for the presence of hip flexion contracture.

If no concurrent lengthening of the psoas is to be performed, surgery may be performed supine or prone. However, if the psoas is to be lengthened, then supine positioning is preferred.

If no concurrent lengthening of the psoas is to be performed, surgery may be performed supine or prone. However, if the psoas is to be lengthened, then supine positioning is preferred.

In the prone position, the patient is positioned on the chest and iliac crest bolsters are placed transversely to decompress the abdomen.

In the prone position, the patient is positioned on the chest and iliac crest bolsters are placed transversely to decompress the abdomen.

In the supine position, each leg is free draped to allow for intraoperative examination of the hip, knee, and ankle.

In the supine position, each leg is free draped to allow for intraoperative examination of the hip, knee, and ankle.

Portals/Exposures

A single incision, 3–6 cm in length, just medial or lateral to the palpable semitendinosus tendon at the mid- to distal third of the posterior thigh can be used to access all the hamstring tendons (Fig. 5).

A single incision, 3–6 cm in length, just medial or lateral to the palpable semitendinosus tendon at the mid- to distal third of the posterior thigh can be used to access all the hamstring tendons (Fig. 5).

Sharp dissection through skin and electrocautery through subcutaneous tissue minimize blood loss.

Sharp dissection through skin and electrocautery through subcutaneous tissue minimize blood loss.

Procedure

Step 1

The muscle-tendon junction of the semitendinosus is palpated. The sheath of the tendon is incised using a #15 blade or electrocautery.

The muscle-tendon junction of the semitendinosus is palpated. The sheath of the tendon is incised using a #15 blade or electrocautery.

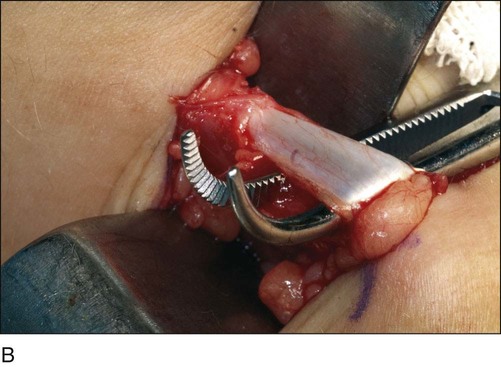

A right-angle clamp is placed around the tendon from lateral to medial to prevent inadvertent injury to the neurovascular bundle (Fig. 6A and 6B).

A right-angle clamp is placed around the tendon from lateral to medial to prevent inadvertent injury to the neurovascular bundle (Fig. 6A and 6B).

Electrocautery is used to amputate the semitendinosus at the level of the musculotendinous junction.

Electrocautery is used to amputate the semitendinosus at the level of the musculotendinous junction.

If the semitendinosus is being used for rectus femoris transfer, then amputation occurs slightly more proximal to ensure sufficient length to facilitate the transfer.

If the semitendinosus is being used for rectus femoris transfer, then amputation occurs slightly more proximal to ensure sufficient length to facilitate the transfer.![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

33: Knee Surgery for Children with Cerebral Palsy