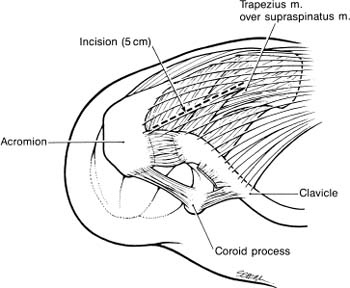

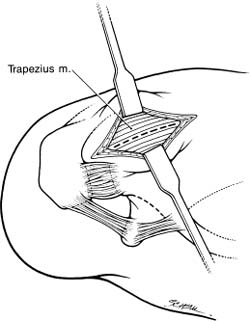

Case 30 A 37-year-old laborer presents with an 8-month history of left shoulder pain and weakness. He describes the pain as primarily achy in character and worse with overhead use of his arm. He also reports progressive weakness of his shoulder, limiting his ability to work as a carpenter. He denies any numbness or tingling in his arm and any neck symptoms. He also denies any specific incident or injury that initiated his symptoms. The patient has 150 degrees of active forward flexion and 170 degrees of passive forward flexion. He has normal active and passive external rotation. However, testing demonstrates 4/5 forward flexion strength and 3/5 external rotation strength. Translation testing demonstrates normal stability of the shoulder. He has a negative apprehension and relocation test. He has a positive Neer impingement sign and a positive Hawkins impingement sign. Further examination of his shoulder and shoulder girdle demonstrate no tenderness, but asymmetry of his shoulder blade without winging is noted. There appears to be atrophy of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus fossae. 1. Cervical radiculopathy 2. Suprascapular neuropathy 3. Massive rotator cuff tear An anteroposterior (AP), scapular Y, and axillary view of the shoulder failed to reveal any obvious abnormalities. Suprascapular Neuropathy. Atrophy of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles combined with significant weakness of external rotation and the absence of a specific traumatic injury in this otherwise healthy manual laborer suggests suprascapular neuropathy. A nontraumatic massive rotator cuff tear in an otherwise healthy active young laborer would be distinctly unusual. The suprascapular nerve originates from the upper trunk of the brachial plexus formed by the roots of C5 and C6 at Erb’s point. The nerve courses downward and parallel to the omohyoid muscle beneath the trapezius to the superior edge of the scapula. It then runs through the suprascapular notch. The roof of the notch is formed by the transverse scapular ligament. Entrapment of the suprascapular nerve is an acquired pathologic condition that is often severe and disabling. It can mimic many other painful shoulder conditions. Accordingly, it is often misdiagnosed, thereby delaying correct treatment and potentially worsening the disability associated with this condition. PEARLS • Extensive exposure of the posterior glenoid neck and spin-oglenoid notch is sometimes required when ganglion cysts are present. For this reason, the posterior approach is often preferable. The superior approach, although advantageous in its exposure of the suprascapular notch, can provide only limited access to the spinoglenoid notch when decompression of the nerve more distally is required. • Careful preoperative evaluation of the shoulder radiographs will allow for accurate determination of the suprascapular notch size and configuration. This knowledge of suprascapular notch anatomy will improve the surgeon’s approach to the nerve. It will also help determine whether bony decompression around the nerve is required at the time of transverse scapular ligament release. The choice of operative versus nonoperative treatment for suprascapular neuropathy depends on a number of factors. Patients with significant evidence of denervation, progressive weakness, and pain, or symptoms unresponsive to nonoperative measures, are treated surgically. The choice of surgical approach depends on the MRI findings and the likely site of compression of the nerve. The most common site for compression of the suprascapular nerve is under the transverse scapular ligament along the border of the superior scapula. When a ganglion cyst is present, arthroscopic decompression is often possible and routinely attempted by the authors. In the absence of a large ganglion cyst or other mass inferior to the transverse scapular ligament, the authors prefer a superior approach. The superior approach to the suprascapular nerve can be carried out with the patient in the lateral decubitus or beach chair position. When MRI or clinical examination suggests intraarticular pathology such as a labrum tear, superior labrum anterior and posterior (SLAP) lesion, or rotator cuff tear, shoulder arthroscopy is performed prior to exploration of the suprascapular nerve. The authors have found that a significant percentage of patients with suprascapular nerve compression due to ganglion cyst formation often have treatable intraarticular lesions. Posterosuperior labrum tears, SLAP lesions, and rotator cuff tears are commonly found. After treatment of the intraarticular pathology, the suprascapular nerve can be exposed through a superior approach. However, the specific approach to the suprascapular nerve must be individualized based on whether a ganglion cyst is identified by MRI and, if so, the position and extent of the cyst. In large cysts extending inferiorly around the posterior scapular neck, a posterior approach may be more suitable. If a superior approach is appropriate, a 5-cm lateral incision is made midway between the spine of the scapula and the clavicle (Fig. 30–1). Superficial dissection allows for visualization of the trapezius muscle (Fig. 30–2). Blunt dissection is used to split the lateral portion of the trapezius in line with its fibers. The split should not proceed more medial than a point half the distance from the tip of the acromion to the midline, to avoid denervating the lower portion of the trapezius. The surgeon will usually encounter a small nerve crossing the medial portion of the trapezius that is easily palpable and helps define the medial limit of dissection. A small amount of fat and a thick fascial layer often cover the top of the underlying supraspinatus, which may be atrophic. Gentle, blunt dissection is used to locate the anterior edge of the supraspinatus fossa, which is followed laterally until the suprascapular notch is identified. It is located just lateral to the origin of the omohyoid muscle. It is not necessary or desirable to fully mobilize the supraspinatus. The suprascapular vessels are identified superior to the transverse scapular ligament and gently retracted. The ligament is then divided while protecting the underlying suprascapular nerve (Fig. 30–3). The notch can also be enlarged at this time, if necessary. A swelling or enlargement of the nerve may occasionally be seen proximal to its entry point through the notch. Figure 30–1. Placement of the incision is midway between the clavicle and the spine of the scapula. Figure 30–2. After making the skin incision, the underlying trapezius muscle is identified and can be split in line with its fibers. The supraspinatus muscle can then be gently retracted anteriorly, providing access to the spinoglenoid notch. The nerve can be assessed for possible compression by digital palpation, but access to this region for decompression is limited. An infra-spinatus approach is sometimes necessary depending on the preoperative clinical and MRI findings. After ensuring adequate decompression of the nerve in this region, the supraspinatus is allowed to fall back into its anatomic position in the supraspinatus fossa. The trapezius is repaired and the skin is closed in a routine manner. A drain is often placed prior to closure of the skin incision. PITFALLS • Failure to recognize concurrent intraarticular shoulder pathology may lead to persistent shoulder symptoms, even after successful decompression of the suprascapular nerve. • Failure to identify a ganglion cyst either preoperatively or intraoperatively may lead to persistent symptoms, even after release of the transverse scapular ligament. For this reason, MRI scans are recommended by the authors in any patient with documented suprascapular nerve compression.

History and Physical Examination

Differential Diagnosis

Radiologic Findings

Diagnosis

Surgical Management

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree