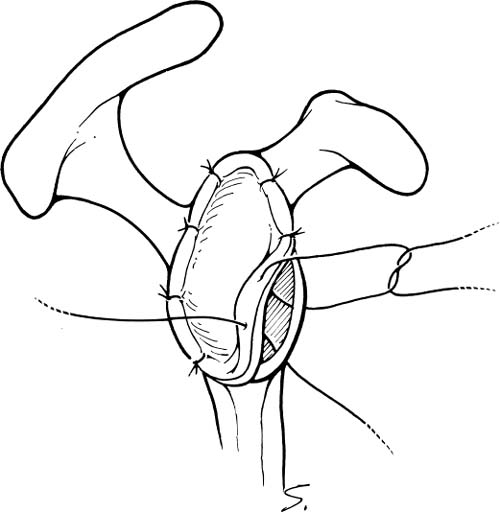

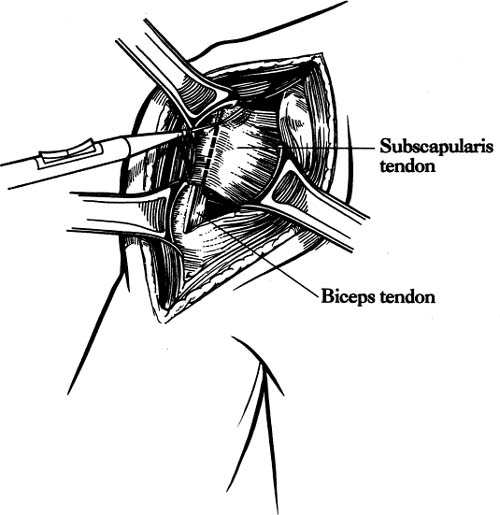

Case 25 A 73-year-old woman presents to the office with a several-year history of intermittent shoulder pain. Over the year prior to presentation, she has experienced increased pain and decreased motion of the shoulder. She denies any specific incident or injury that initiated or worsened her symptoms. She complains of night pain and achiness associated with activity that is partially relieved with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications. She denies any numbness or weakness of her upper extremity or any neck symptoms. The patient exhibits active forward flexion of 110 degrees and passive of 135 degrees. She has passive and active external rotation of 10 degrees along with painful crepitation to range of motion. She has 4/5 supraspinatus strength and normal external rotation strength. She is neurovascularly intact to examination and demonstrates no tenderness to palpation around the shoulder. Figure 25–1. An anteroposterior (AP) (A), scapular Y (B), and axillary (C) radiograph of the patient’s shoulder. 1. Full-thickness rotator cuff tear 2. Glenohumeral osteoarthritis 3. Rotator cuff arthropathy 4. Rotator cuff tendinitis An anteroposterior (AP), scapular Y, and axillary view of the shoulder are obtained (Fig. 25–1). Glenohumeral Osteoarthritis. The history of slow but progressive deterioration of shoulder function along with the physical examination findings of crepitation and loss of motion suggest glenohumeral osteoarthritis. Chronic rotator cuff tears can present similarly, but radiographs confirm the diagnosis of glenohumeral joint arthritis. Although rotator cuff tears can occur in conjunction with significant glenohumeral joint changes, good active motion is preserved and near-normal strength is maintained in this patient, suggesting an intact rotator cuff. Radiographs generally make the diagnosis of significant glenohumeral arthritis a straightforward one, but accurate assessment of the degree of degeneration, particularly as it concerns the glenoid, is not as easy to accurately determine. Progressive posterior glenoid erosion sometimes occurs with dramatic losses of glenoid bone stock. Recognition of the true glenoid version prior to shoulder replacement is important so as to adequately prepare for shoulder replacement. Computed tomography (CT) scanning is the best test to assess glenoid version, and such testing should be obtained when there is concern over significant glenoid retroversion (Fig. 25–2). Axillary views often fail to accurately reflect the true glenoid version that exists due to scapular rotation. The AP radiograph generally demonstrates significant osteophyte formation, subchondral sclerosis, and joint narrowing. Some slight proximal humeral head migration can be seen radiographically, but moderate to severe subluxation of the humeral head is more suggestive of a massive rotator cuff tear in combination with significant humeral head collapse. This combination of radiographic findings is more compatible with rotator cuff arthropathy. Figure 25–2. An axial computed tomography (CT) image of the same patient demonstrating approximately 45 degrees of glenoid retroversion. Nonoperative measures designed to improve the symptoms of patients with significant glenohumeral arthritis mainly consists of medications, gentle exercises, and the judicious use of corticosteroids. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications are often helpful when given intermittently for mild symptoms. A gentle rotator cuff program focusing on motion and strengthening can also be of value in less severe cases of glenohumeral arthritis. More severe cases will not usually respond to these nonoperative measures, making operative intervention much more likely. The type of surgical intervention for glenohumeral arthritis depends on a number of factors. The degree of degeneration helps to determine the most appropriate operation. This information, combined with the age and activity level of the patient, aids in formulating a treatment plan. For example, active patients who are relatively young and who exhibit mild glenohumeral arthritis radiographically may respond to arthroscopic glenohumeral joint debridement. Although few studies are available to assess the long-term outcome of arthroscopic glenohumeral joint debridement, some clinical improvement is generally seen after surgery. Arthroscopic debridement of the glenohumeral joint also allows for an accurate assessment of the degree of degeneration of both the glenoid and humeral head. Often, radiographs may not accurately represent the significant articular loss and degeneration seen at arthroscopy. This information can be valuable in the management of the patient’s condition. When arthroscopic glenohumeral joint debridement is carried out, standard anterior and posterior portals are established. A thorough diagnostic arthroscopy focusing on the status of the rotator cuff, the biceps tendon, and the articular surfaces of the glenoid and humeral head is carried out. Thorough debridement of the frayed labrum and any partial tearing of the cuff are completed, after which any significant osteophytes are removed arthroscopically. Often, inferior humeral head osteophytes are seen both radiographically and clinically. These osteophytes are excised arthroscopically. The rotator cuff is then evaluated from the subacromial space, and a bursectomy is performed if reactive thickened bursa is encountered. This allows for accurate assessment of the status of the bursal surface of the rotator cuff. If a full-thickness rotator cuff tear is encountered, a mini-open or purely arthroscopic rotator cuff repair is usually carried out after an arthroscopic acromioplasty is completed. The authors have found this surgical procedure to be valuable in relatively young patients with mild glenohumeral joint arthritis. The postoperative improvement in clinical symptoms is important not only because the patients are functionally better and pleased after the surgery, but also because this less invasive procedure will eliminate or at least delay the necessity for shoulder replacement surgery. Younger patients with severe glenohumeral joint arthritis present a difficult challenge. Traditionally, these patients have been denied total shoulder arthroplasty and have been considered candidates for glenohumeral fusion, particularly when their occupations involve heavy labor. Accelerated loosening of polyethylene glenoid components and increased polyethylene wear are theoretic concerns in offering total shoulder arthroplasty to young patients. An alternative to total shoulder arthroplasty involves humeral head replacement alone in these patients. However, when compared with total shoulder arthroplasty, hemiarthroplasty has been found to be inferior with regard to pain relief and return of motion and function. Another option in the management of this difficult clinical situation involves the biologic resurfacing of the glenoid in conjunction with a porous-coated humeral head replacement. Biologic resurfacing of the glenoid is accomplished using either a portion of the anterior shoulder capsule or a free fascia lata autograft obtained at the time of surgical intervention. Using a standard dectopectoral approach, the subscapularis is released either at its insertion on the humerus or using a coronal Z-plasty technique, depending on the degree of external rotation loss. Following resection of the degenerated humeral head in approximately 20 to 30 degrees of external rotation, the glenoid is visualized and the surface abraded down to bleeding subchondral bone. Drill holes are placed into and through the subchondral bone so as to stimulate healing. Any residual labral tissue is retained if it is strong enough to hold a suture. Fascia lata autograft is then harvested from the ipsilateral thigh if necessary and is laid onto the glenoid surface with the outer or articular surface corresponding to the exterior surface of the fascia lata. Sutures are then placed through the drill holes or the labrum and this graft secured into position on the glenoid face (Fig. 25–3). The humeral component is then press fit and an appropriate humeral head impacted onto the shaft component. The subscapularis Z-plasty or release is then repaired using standard technique. Older, less active patients with moderate to severe glenohumeral arthritis are the best candidates for total shoulder arthroplasty. Several factors are important in planning for total shoulder arthroplasty. The adequacy and orientation of the glenoid must be accurately determined so as to ensure proper humeral head version and adequate glenohumeral stability. Likewise, intraoperative determination of the status of the rotator cuff plays an important role in determining whether or not a glenoid component should be utilized. Figure 25–3. Fascia lata autograft is sutured to the abraded glenoid articular surface. The patient is placed in the beach chair position on the operating table. The patient must be lateralized over the edge of the table and the head supported so as to allow for free draping of the involved extremity. Also, the ability to extend the arm and shoulder over the corner of the table must be assured as humeral broaching and component placement require such positioning. A deltopectoral incision is made. The cephalic vein is identified and generally retracted laterally with the deltoid. The underlying subscapularis tendon is identified and released either at its insertion on the lesser tuberosity or using a coronal Z-plasty technique. The method of release of the subscapularis depends on the amount of external rotation present at the time of surgery. Some external rotation can be gained by releasing the subscapularis from its insertion on the lesser tuberosity and then repairing this tendinous tissue back to the cut surface of the humeral head following implant placement. When more external rotation must be recovered, a coronal Z-plasty technique is preferred (Fig. 25–4). A general rule for external rotation recovery with Z-plasty lengthening is that 1 cm of lengthening corresponds to an increase of 10 degrees of external rotation. Following release of the subscapularis tendon, the underlying capsule is released from the humerus and any scarred and thickened capsule is excised. The humeral head is then visualized by extending the shoulder. A proper humeral head resection is important not only to allow for concentric reduction of the humeral head within the glenoid, but also to serve to maximally stabilize the humeral component. Most shoulder replacement systems have a guide designed to ensure that the proper angle for humeral head resection is adhered to. Too vertical a cut may compromise the stability of the humeral component. The position of the arm when the humeral head is resected depends primarily on the version of the glenoid. When there is significant glenoid retroversion, decreased version of the humeral component should be used unless the glenoid version is to be significantly altered, either by resecting a portion of the anterior glenoid or by using a reconstructive technique employing a posterior bone block. Following resection of the humeral head, various broaches and trials can be employed until the proper size for the humeral component is determined. A humeral trial component is generally left within the medullary canal to help protect the resected surface of the humeral head, and a humeral head retractor is then placed into the joint. The glenoid is visualized and labral tissue excised. Depending on the system employed, a keeled recess or peg holes are placed into the glenoid articular surface after contouring of the glenoid articulation is completed. A trial glenoid component is placed and motion and stability within the glenohumeral articulation are assessed. Figure 25–4. Coronal Z-plasty technique for subscapularis release performed when necessary. After determining humeral component and glenoid sizes, cement is placed into the recessed keel hole or peg holes and the glenoid component held into position. Following hardening of the cement, the humeral component is placed. The great majority of humeral components can usually be placed using a press-fit technique, but cement should be employed when adequate stability cannot be achieved. The Z-plasty of the subscapularis tendon is then repaired and standard closure accomplished (Fig. 25–5). PEARLS • Care should be taken to avoid overresection of the deformed humeral head. Conservative removal of humeral head will preserve adequate bone stock and still allow for subsequent removal of additional humeral head if necessary. • Adequate capsular release, particularly inferiorly, allows for significantly improved access to the glenoid, making glenoid surface replacement easier. Palpation of the axillary nerve during inferior capsular release minimizes risk to the nerve.

History and Physical Examination

Differential Diagnosis

Radiologic Findings

Diagnosis

Surgical Management

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree