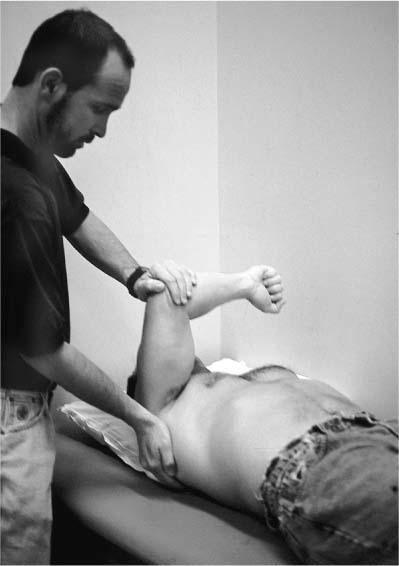

Case 14 A 20-year-old right-hand-dominant college football offensive lineman presents with a 3-month history of right posterior shoulder pain and shoulder popping following an on field injury. This patient demonstrates a normal range of shoulder motion except for a four-vertebral-level loss of internal rotation. His rotator cuff strength is normal. There is no atrophy or asymmetry of the shoulder musculature. Translation testing demonstrates normal anterior translation, but 2+ increased posterior translation. There is no appreciable sulcus sign. He also exhibits pain in the posterior shoulder when a posterior compression force is applied to the arm in a position of 90-degree forward flexion and maximal internal rotation (Fig. 14–1). The patient has a negative apprehension test and a negative relocation test. Figure 14–1. The posterior instability compression test is accomplished by applying a posteriorly directed force on the arm while the shoulder is held in 90-degree forward flexion and full internal rotation. 1. Suprascapular nerve injury 2. Full-thickness rotator cuff tear 3. Posterior shoulder instability 4. Superior labrum anterior and posterior (SLAP) lesion A three-view trauma series of X-rays including an anteroposterior (AP) X-ray, an axillary view, and a scapular Y view failed to reveal any obvious abnormalities. Posterior Shoulder Instability. The diagnosis of posterior shoulder instability is made primarily based on the history of a traumatic on-field injury in an athlete susceptible to such an instability pattern, along with a physical examination that clearly demonstrates increased posterior translation. The posterior compression-rotation test performed as shown in Figure 14–1 is a sensitive measure of posterior labral and ligamentous pathology. Although some patients with posterior instability complain of recurrent subluxation, or even frank dislocations, most complain only of shoulder pain. Football players in at-risk positions such as linemen are particularly susceptible to posterior instability. An offensive linemen is required to resist posterior compression forces by blocking defensive linemen with his arm in a forward flexed, abducted, and internally rotated position. Linemen are also generally involved in strenuous weight-lifting exercises. Bench press exercises in these very powerful athletes can sometimes predispose to posterior labral fraying, and even capsular stretching, resulting in posterior instability symptoms. Translation testing can be performed with the patient either in the supine position or sitting. If the test is performed with the patient sitting, the examiner must be careful to stabilize the scapula. Shoulder translation can be graded according to the shift of the humeral head on the glenoid. Translation of 1+ represents increased translation compared to the opposite extremity, but it is insufficient to cause subluxation of the humeral head over the glenoid rim. An increased translation of 2+ represents the ability of the examiner to sublux the humeral head over the glenoid rim, but the head spontaneously reduces when the translation force is eliminated. Finally, a 3+ increased translation represents the ability of the examiner to dislocate the humeral head without spontaneous reduction (locked dislocation). The importance of comparison with the contralateral shoulder cannot be overstated. This is particularly true as it relates to posterior shoulder translation because posterior translation up to 50% of the diameter of the humeral head on the glenoid is commonly seen in normal subjects. Patients with posterior shoulder instability often respond to an extensive exercise program. Those patients who fail a nonoperative treatment program consisting of vigorous physical therapy and medication, and who remain functionally impaired by the instability, can benefit significantly from surgery. The authors have found that unlike anterior instability, no “essential” lesion is responsible for posterior instability. As a result, numerous surgical procedures to correct this instability pattern have been described including bone block procedures, glenoid osteotomies, and McLaughlin-type procedures. Posterior capsular procedures such as reverse Bankart repairs, reverse Putti-Platt procedures, and posterior-inferior capsular shift procedures have also been utilized. In addition, arthroscopic repair techniques have recently been described. PEARL • Arthroscopic rotator interval plication should be considered on a routine basis in these patients, as its role in limiting posterior translation has been clearly demonstrated in cadaveric studies. PITFALLS • Making an accurate diagnosis of posterior instability is often difficult even for the experienced clinician. A complete and thorough physical examination, particularly for patients at risk for posterior instability, should be carried out. • Arthroscopic posterior shoulder stabilization is a technically demanding procedure and requires extensive experience in arthroscopic shoulder stabilization. The surgeon should maintain a low threshold for performing an open posterior shoulder stabilization when difficulties are encountered. Also, the axillary nerve is at significant risk with these arthroscopic procedures, and care should be taken to maintain visualization of all arthroscopic instruments during the procedure.

History and Physical Examination

Differential Diagnosis

Radiologic Findings

Diagnosis

Surgical Management

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree