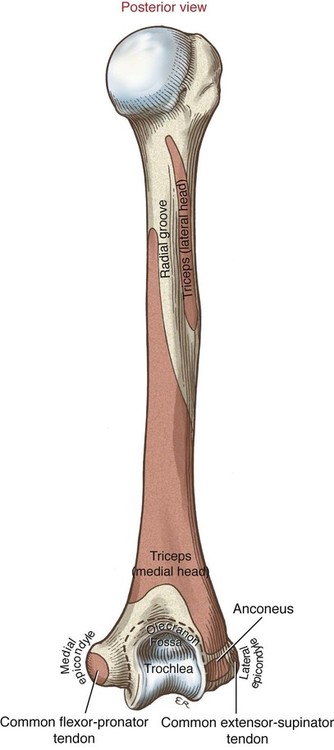

• Identify the primary bones and bony features relevant to the elbow and forearm complex. • Describe the supporting structures of the elbow and forearm complex. • Describe the structure and function of the four main joints within the elbow and forearm complex. • Cite the normal range of motion for elbow flexion and extension and for forearm supination and pronation. • Describe the planes of motion and axes of rotation for the joints of the elbow and forearm complex. • Cite the proximal and distal attachments and innervation of the muscles of the elbow and forearm complex. • Justify the primary actions of the muscles of the elbow and forearm complex. • Cite innervation of the muscles of the elbow and forearm complex. • Explain the primary muscular interactions involved in performing a pushing and pulling motion. • Explain the primary muscular interactions involved in tightening a screw with a screwdriver. The ability to actively flex and extend the elbow is essential for many important functions such as those involved with feeding, grooming, reaching, throwing, and pushing. The elbow itself actually consists of two separate articulations: the humeroulnar and the humeroradial joint (Figure 5-1). The forearm complex allows the movements of pronation and supination—motions that rotate the palm upward (supination) or downward (pronation). Similar to the elbow, the forearm consists of two articulations: the proximal and distal radioulnar joint (Figure 5-1). The interaction among the four joints of the elbow and forearm enables the hand to be placed in a nearly infinite number of positions, greatly enhancing the functional potential of the entire upper extremity. The scapula has three bony features that are important to the muscles of the elbow. The coracoid process serves as the proximal attachment for the short head of the biceps. The supraglenoid tubercle serves as the proximal attachment for the long head of the biceps. The infraglenoid tubercle marks the proximal attachment for the long head of the triceps. These bony landmarks were reviewed in the previous chapter (see Figure 4-4). The trochlea is a spool-shaped structure located on the medial side of the distal humerus (Figures 5-2 and 5-3) that articulates with the ulna to form the humeroulnar joint. The coronoid fossa is a small pit located just superior to the trochlea that accepts the coronoid process of the ulna when the elbow is fully flexed. Just lateral to the trochlea is the ball-shaped capitulum, which articulates with the head of the radius to form the humeroradial joint. The ulna (Figures 5-4 and 5-5) has a thick proximal end with distinct processes. The olecranon process is the large, blunt, proximal tip of the ulna commonly referred to as the elbow bone. The rough posterior surface of the olecranon process is the distal attachment for the triceps muscles. The trochlear notch is the large, jaw-like curvature of the proximal ulna that articulates with the trochlea (of the humerus), forming the humeroulnar joint (Figure 5-6). The inferior tip of the trochlear notch comes to a point, forming the coronoid process. The coronoid process strengthens the articulation of the humeroulnar joint by firmly grabbing the trochlea of the humerus. Slightly inferior and lateral to the trochlear notch is the radial notch, which articulates with the head of the radius to form the proximal radioulnar joint. In a fully supinated position, the radius lies parallel and lateral to the ulna (see Figures 5-4 and 5-5). The radial head is shaped like a wide disc on the proximal end of the radius. The superior surface of the radial head consists of a shallow, cup-shaped depression called the fovea that articulates with the capitulum of the humerus, forming the humeroradial joint. As was mentioned in the previous section, the elbow joint is composed of two articulations: the humeroulnar joint and the humeroradial joint. The humeroulnar joint provides most of the structural stability to the elbow as a whole. This stability is provided primarily by the jaw-like trochlear notch of the ulna interlocking with the spool-shaped trochlea of the humerus (Figure 5-6). This hinge-like joint limits the motion of the elbow to flexion and extension. The humeroradial joint is formed by the ball-shaped capitulum of the humerus articulating with the bowl-shaped fovea of the radius (Figure 5-7). This configuration permits continuous contact between the radial head and the capitulum during supination and pronation, as the radius spins about its own axis; and during flexion and extension, as the radial head rolls and slides over the rounded capitulum. Compared with the humeroulnar joint, the humeroradial joint provides only secondary stability to the elbow. With the forearm supinated and the elbow fully extended, it should be evident that the forearm projects laterally about 15 to 20 degrees relative to the humerus. This natural outward angulation of the forearm within the frontal plane is called normal cubitus valgus (Figure 5-8); valgus literally means to “bend outward.” The natural cubitus valgus orientation is also called the carrying angle because of its apparent function of keeping a carried object away from the body. Trauma to the elbow can alter the normal valgus angle, resulting in excessive cubitus valgus (Figure 5-8, B) or cubitus varus (Figure 5-8, C). The primary function of the collateral ligaments is to limit excessive varus and valgus deformations of the elbow. The medial collateral ligament is most often injured during attempts to catch oneself from a fall (Figure 5-10). Because these ligaments also become taut at the extremes of flexion and extension, the extremes of these sagittal plane motions—if sufficiently forceful—can damage the collateral ligaments. The following structures are illustrated in Figure 5-9: • Articular Capsule: A thin, expansive band of connective tissue that encloses three different articulations: the humeroulnar joint, the humeroradial joint, and the proximal radioulnar joint • Medial Collateral Ligament: Contains fibers that attach proximally to the medial epicondyle and distally to the medial aspects of the coronoid and olecranon processes; provide stability primarily by resisting cubitus valgus–producing forces. This ligament is also called the ulnar collateral ligament. • Lateral Collateral Ligament: Originates on the lateral epicondyle and ultimately attaches to the lateral aspect of the proximal forearm. These fibers provide stability to the elbow by resisting cubitus varus–producing forces. This ligament is also referred to as the radial collateral ligament. From the anatomic position, elbow flexion and extension occur in the sagittal plane about a medial-lateral axis of rotation, which courses through both epicondyles. The range of motion at the elbow normally spans from 5 degrees beyond extension to 145 degrees of flexion (Figure 5-11). Most typical activities of daily living, however, use a more limited 100-degree arc of motion, between 30 and 130 degrees of flexion. Excessive extension is normally limited by the bony articulation between the olecranon and the olecranon fossa. The forearm is composed of the proximal and distal radioulnar joints (see Figure 5-1). As the names imply, these joints are located at the proximal and distal ends of the forearm. Pronation and supination occur as a result of motion at each of these two joints. As is shown in Figure 5-12, A, in full supination, the radius and the ulna lie parallel to one another. However, in full pronation, the radius crosses over the ulna (Figure 5-12, B). As is emphasized in subsequent sections of this chapter, pronation and supination involve the radius rotating around a relatively fixed ulna. Although pronation and supination are typically used to describe motions or positions of the hand, these motions occur at the forearm. However, it is useful to observe this motion by noting the position of the hand relative to the humerus. The firm articulation between the distal radius and the carpal bones (at the wrist) requires that the hand follow the rotation of the radius; the ulna typically remains relatively stationary because of its firm attachment at the humeroulnar joint. • Annular Ligament: A thick circular band of connective tissue that wraps around the radial head and attaches to either side of the radial notch of the ulna (see Figures 5-9 and 5-13). This ring-like structure holds the radial head firmly against the ulna, allowing it to spin freely during supination and pronation. • Distal Radioulnar Joint Capsule: Reinforced by palmar and dorsal capsular ligaments, this structure provides stability to the distal radioulnar joint. • Interosseous Membrane (see Figure 5-5): Helps bind the radius to the ulna; serves as a site for muscular attachments, and as a mechanism to transmit forces proximally through the forearm Supination and pronation occur as the radius rotates around an axis of rotation that travels from the radial head to the ulnar head (see Figure 5-12). The 0-degree or neutral position of the forearm is the thumb-up position (Figure 5-14). From this position, 85 degrees of supination and 75 degrees of pronation normally occur. People who lack full range of motion of these movements often compensate by internally or externally rotating the shoulder, so clinicians must be aware of this possible substitution when testing the range of motion of the forearm. Supination and pronation occur as a result of simultaneous motion at the proximal and distal radioulnar joint; therefore, a restriction at one joint will result in limited motion at the other. With the humerus fixed and the forearm free to move, the arthrokinematics of supination and pronation is based on the following three premises (Figure 5-17):

Structure and Function of the Elbow and Forearm Complex

Osteology

Scapula

Distal Humerus

Ulna

Radius

Arthrology of the Elbow

General Features

Supporting Structures of the Elbow Joint

Kinematics

Arthrology of the Forearm

General Features

Supporting Structures of the Proximal and Distal Radioulnar Joints

Kinematics

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Structure and Function of the Elbow and Forearm Complex